Poverty and inequality

Poverty is both a driver and consequence of disasters, and the processes that further disaster risk related poverty are permeated with inequality.

On this page:

- Poverty and vulnerability

- Disaster risk and inequality

- Opportunities for building resilience

- Resources on poverty

- Related sections on PreventionWeb

Socio-economic inequality is likely to continue to increase and with it disaster risk for those countries, communities, households and businesses that have only limited opportunities to manage their risks and strengthen their resilience.

The geography of inequality expresses itself at all scales: between regions and countries, within countries and inside cities and localities. This is particularly clear with the relationship between the proportion of population below the international poverty line and the number of people affected by disasters.

The figure below highlights the disparities between the region of Europe and North America and the subregion of sub-Saharan African in terms of the relationship between poverty and direct economic loss attributed to disasters in 2021.

UN DESA analysis based on Global Sustainable Development Goal Indicators Database (UN DESA, 2021)

Poverty and vulnerability

Vulnerability is not simply about poverty, but extensive research over the past 30 years has revealed that it is generally the poor who tend to suffer worst from disasters.

Impoverished people are more likely to live in hazard-exposed areas and are less able to invest in risk-reducing measures. The lack of access to insurance and social protection means that people in poverty are often forced to use their already limited assets to buffer disaster losses, which drives them into further poverty.

89% of the 1.5 billion people exposed to floods live in low and middle income countries.

World Bank, 2022

Poverty is therefore both a cause and consequence of disaster risk, particularly extensive risk, with drought being the hazard most closely associated with poverty. The impact of disasters on the poor can, in addition to loss of life, injury and damage, cause a total loss of livelihoods, displacement, poor health, food insecurity, among other consequences.

You can’t talk about disaster risk reduction without talking about inequality

Evacuation as a primary safety measure for any number of disaster types may sound simple enough, but research shows even that’s not always easy for poorer, disadvantaged people.

Recovery after disaster can extremely uneven within communities — especially in regards to housing and job markets — which can help compound pre-existing inequalities.

Poorer, more disadvantaged people are less likely to be able to afford household insurance, exposing them to even greater risk.

Learn more

Climate change and exposure to natural hazards threaten to derail international efforts to eradicate poverty by 2030. Shepherd, A. at al. 2013

Research suggests that disasters cause impoverishment, which can lead to a cycle of losses, poverty traps and a slowing of efforts to reduce poverty. However, not every disaster leads to such negative long-term impacts and recovery can be relatively quick in some countries compared to others - with notable differences between and among different socio-economic groups.

During the pandemic and cost-of-living crisis years since 2020, $26 trillion (63 percent) of all new wealth was captured by the richest 1 percent, while $16 trillion (37 percent) went to the rest of the world put together. Oxfam International, 2023

Uneven impacts of disasters

While absolute losses tend to be higher amongst wealthier groups, the relative impact of disasters on low-income households is far greater.

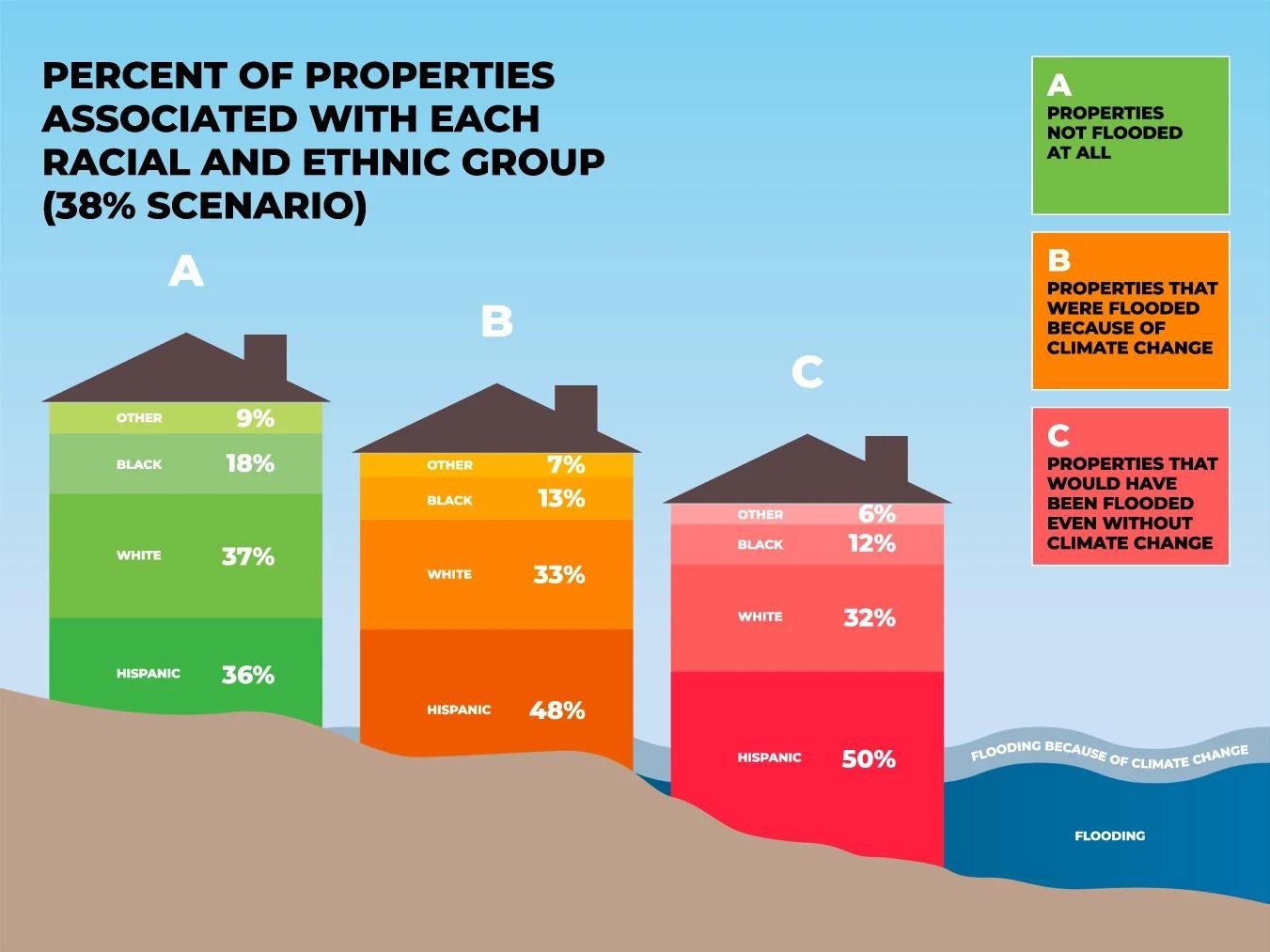

Take the example of Hurricane Harvey in 2017 - in Harris County, Texas, the per capita damages for a Latina/x/o person from climate change-attributed flooding were estimated at ~$1,035. Although this estimate is only narrowly higher than that for whites ($828), it should be noted that home values are higher in white neighborhoods. The illustration below, taken from this study, shows the proportion of different racial groups in each affected neighborhood under the scenario of where 27cm of flood depth is attributed to climate change. This illustrates that natural hazards boosted by climate change are and will be affecting disproportianetly less privileged neighorhoods.

Disaster risks in rural areas may be particularly invisible, given the low density of produced capital and declining population. Poor rural livelihoods are highly exposed and vulnerable to weather-related hazards and have a low resilience to loss because they have little or no surplus capacity to absorb crop or livestock income losses and to recover. Even a small loss might feed back into further poverty and future vulnerability.

Asking people to prepare for fire is pointless if they can't afford to do it

For years, authorities have essentially handed people a very formidable and expensive checklist of things to do, right up to the level of retrofitting your house to be compliant with modern building standards. These are significant time and financial investments.

There are many reasons people don’t prepare, and a key one is affordability. If you’re not physically able to get up a ladder to clean your gutters or mow around your property and remove fuel load — and you can’t afford to pay someone to do it — what are you supposed to do?

It’s time to look at preventative fire measures the same way we look at preventative healthcare.

Read more

Poverty and disaster risk are also pervasive in urban areas. Generally, poor urban households derive most or all their income from work in the informal economy, meaning that precise figures on urban poverty are lacking.

Climate change could push more than 130 million people into extreme poverty by 2030.

World Bank, 2020

Housing is usually the principal economic asset of poor urban households, providing not only shelter and personal security, but also often their livelihood. Damage or loss to housing, together with essential domestic possessions, therefore, places enormous strain on household economies, given the high monetary cost of replacing lost assets, relative to low and irregular incomes, and the absence of insurance or safety nets.

Urban poverty is now understood to have many additional dimensions - including 'voicelessness' and 'powerlessness', and inadequate provision of infrastructure and basic services. Most of the immediate causes of the deprivations associated with urban poverty are risk related.

Inequality is not just about the unequal distribution of income.

Disaster risk and inequality

Disaster risk is shaped by a range of social and economic factors that determine entitlements and capabilities. Access to services, political voice, and social and economic status directly affect disaster risk and resilience.

Key factors in underprivileged areas include low-quality and insecure housing, which in turn limits access to basic services such as health care, public transport, communications, and infrastructure such as water, sanitation, drainage and roads. Higher mortality and morbidity rates among children, the elderly and women are directly linked to these different poverty factors.

Inequality facilitates the transfer of disaster risks from those who benefit from risk taking to those who bear the cost, through ineffective accountability and increased corruption. Inequality is linked to other risk drivers, since it redistributes disaster risk through uneven economic development, segregated urban development, climate change and the overconsumption of resources. If inequality continues to rise, it may become a destabilising global force that manifests not only in increasing disaster risk but also in decreasing capacities to manage those risks. https://www.youtube.com/embed/TH3LQW8B2Zw

Opportunities for building resilience

Poverty and inequality drive vulnerability, but even the vulnerable have some capacities to cope with disasters. Strengthening these capacities, so long as they address needs and disaster risk in the long-term, and not simply the short-term, can enable communities to recover from disasters.

By enhancing resilience, households and society can also prosper in the face of disasters, breaking the cycle of disasters creating and being driven by poverty.

Strengthening livelihoods

Strengthening livelihoods and increasing resilience is therefore critical to reducing both disaster risk and poverty. In rural areas, livelihoods are particularly sensitive and vulnerable to weather fluctuations and extremes.

The urban informal economy is growing, providing livelihoods for millions of people and with it environmental pressures – so how it evolves will be critical in transitioning to a more resilient economy. Building resilience in the urban informal economy is about working with and not against the urban poor, improving the formal regulatory systems and the operations of the informal economy.

Livelihood strengthening can have many dimensions, including:

- Infrastructure development and basic services provision

E.g. watershed management, drought proofing, flood risk management, rainwater harvesting, cash for public works, construction of irrigation systems, canals, roads, disaster recovery and reconstruction, etc. - Natural resource management

E.g. agroforestry, sensitive irrigation, watershed restoration, etc. - Social assistance and protection

E.g. livelihood guarantee schemes, cash transfers, subsidies for public services, etc. - Livelihoods diversification

E.g. alternative sources of income that are resilient to different hazards. etc.

Strengthening livelihoods is about building human, social, political, physical, financial and natural assets. Assets perform two key functions: (1) they build capacity through better access to resources, (e.g. education leading to a better paid job) and (2) they reduce vulnerability by acting as the buffer between people and hazards and other shocks and stresses.

Access to the resources people need to build assets is hindered by inequality owing to gender, age, disability or ethnicity based discrimination and legal and illegal control of assets. For instance, women are more prevalent in the low and unpaid segments of the urban informal economy.

Bangladesh: Living with the floods on floating houses

The CORE Bangladesh project aims to develop coordinating capabilities in flood-risk management for the urban/peri-urban poor in Bangladesh. It is lead by Bangladeshi and Dutch stakeholders and is composed of different components.

In this interview, Professor M. Shah Alam Khan explains how the component of amphibious housing can help populations in Bangladesh cope with reoccurring floods: "Taking people’s livelihoods into consideration, we designed it in such a way that the structure can carry the load of handlooms allowing community members to continue their income-generating activities. As a result, and thanks to our design, people can stay in their houses and are not forced to move away from them, which could increase the risk of being robbed."

Read the interview

Households with more assets are less vulnerable because assets provide buffers against disaster loss. For instance, such households might have the opportunity to sell animals if a harvest fails. However, intensive disasters may destroy all assets, reducing the value of these asset buffers.

Similarly, the coping strategies poor households may select (faced with scarcity) include overgrazing, deforestation or unsustainable extraction of water resources. While these provide food and income in the short-term, in the long-term these activities intensify hazards and drive disaster risk. When microfinance schemes and social protection are available, households are less likely to adopt damaging coping capacities.

Social protection

Social protection programs are public interventions aimed at supporting the poor and more vulnerable members of society, as well as helping individuals, families, and communities manage risk.

Social protection includes safety nets (social assistance and non-contributory transfers such as cash transfers, school feeding, targeted food assistance and subsidies), and social insurance (such as old-age, survivorship, disability pensions, and unemployment insurance). Many governments and development agencies invest in social protection programs to address poverty reduction goals and, more recently, disaster risk reduction.

Mozambique: Integrating shock-responsive social protection into anticipatory action protocols

One interesting aspect of Mozambique’s shift towards anticipatory actions for drought is the integration of social protection actors as collaborators in the design and implementation of early actions. These include the National Institute of Social Action and the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Action.

The links between social protection and anticipatory action are diverse. They range from informing social protection cash transfers with pre-defined drought triggers, to robust targeting of the most at-risk population groups ahead of a disaster’s impact.

Read more

Social protection has four basic approaches:

- Protective measures to provide relief;

- Preventive measures to avoid damaging coping strategies;

- Promotive measures to enhance resilience; and,

- Transformative measures to combat discrimination underlying social and political vulnerability (Davies et al., 2008).

Many countries have made substantial gains in poverty reduction and development goals, which have been linked with a reduction in disaster related mortality. Furthermore, during the Hyogo Framework for Action monitoring period (2005 to 2015), food and social welfare sectors have made considerable progress in addressing poverty and inequality - food security is improving in many regions, and social protection coverage is increasing.

However, the ability to invest in social protection remains limited in many countries, with stark differences in the capacity of local governments to meet the needs of citizens.

Resources on poverty

Take a look at the below PreventionWeb resources on poverty.