Disaster Risk

Disaster risk is expressed as the likelihood of loss of life, injury or destruction and damage from a disaster in a given period of time.

UNDRR Global Assessment Report, 2015

Disaster risk is widely recognized as the consequence of the interaction between a hazard and the characteristics that make people and places vulnerable and exposed.

What is disaster risk

There is no such thing as a natural disaster, but disasters often follow natural hazards.

Disasters are sometimes considered external shocks, but disaster risk results from the complex interaction between development processes that generate conditions of exposure, vulnerability and hazard. Disaster risk is therefore considered as the combination of the severity and frequency of a hazard, the numbers of people and assets exposed to the hazard, and their vulnerability to damage. Intensive risk is disaster risk associated with low-probability, high-impact events, whereas extensive risk is associated with high-probability, low-impact events.

Disasters do not discriminate but their impact does. They disproportionately affect the poorest and most vulnerable because they exacerbate structural inequalities. Photo of the impacts of Typhoon Molave in Vetnam (2020). Source: Marco Gallo/Shutterstock

The losses and impacts that characterise disasters usually have much to do with the exposure and vulnerability of people and places as they do with the severity of the hazard event.

Disaster risk has many characteristics. In order to understand disaster risk, it is essential to understand that it is:

- Forward looking the likelihood of loss of life, destruction and damage in a given period of time

- Dynamic: it can increase or decrease according to our ability to reduce vulnerability

- Invisible: it is comprised of not only the threat of high-impact events, but also the frequent, low-impact events that are often hidden

- Unevenly distributed around the earth: hazards affect different areas, but the pattern of disaster risk reflects the social construction of exposure and vulnerability in different countries

- Emergent and complex: many processes, including climate change and globalized economic development, are creating new, interconnected risks

Disasters threaten development, just as development creates disaster risk

The key to understanding disaster risk is by recognizing that disasters are an indicator of development failures, meaning that disaster risk is a measure of the sustainability of development. Hazard, vulnerability and exposure are influenced by a number of risk drivers, including poverty and inequality, badly planned and managed urban and regional development, climate change and environmental degradation.

Understanding disaster risk requires us to not only consider the hazard, our exposure and vulnerability but also society's capacity to protect itself from disasters. The ability of communities, societies and systems to resist, absorb, accommodate, recover from disasters, whilst at the same time improve wellbeing, is known as resilience.

Illustration: Risk dimensions, categories and components retrieved from Bangladesh INFORM Sub-National Risk Index 2022, UNDRR (2022)

Why does disaster risk matter?

If current global patterns of increasing exposure, high levels of inequality, rapid urban development and environment degradation grow, then disaster risk may increase to dangerous levels.

If current trends continue, the number of disasters per year may increase from around 400 in 2015 to 560 per year 2030.

UNDRR, 2022

The average annual direct economic loss from disasters has more than doubled over the past three decades, showing an increase of approximately 145% from an average of around $70 billion in the 1990s to just over $170 billion in the 2010s.

UNDRR, 2022

As the past several decades of research have demonstrated, disasters particularly affect the poorest and most marginalised people, whilst also exacerbating vulnerabilities and social inequalities and harming economic growth. Disaster mortality risk is closely correlated with income level and quality of risk governance. Although some countries have successfully reduced disaster deaths from flooding and tropical cyclones, evidence suggests that the numbers of deaths from extensive risks is increasing. Increases in extensive disaster loss and damage is evidence that disaster risk is an indicator of failed or skewed development, of unsustainable economic and social processes, and of ill-adapted societies.

In most economies 70-85% of overall investment is made by the private sector, which generally does not consider disaster risk in its portfolio of risks. Across the globe, the concentration of high-value assets in hazard areas has grown. But, when disaster losses are understood relative to the income status of the country, low and middle-income countries appear to be suffering the greatest losses. Disaster risk is therefore a problem for people, businesses and governments alike.

How do we measure disaster risk?

Identifying, assessing and understanding disaster risk is critical to reducing it.

We can measure disaster risk by analysing trends of, for instance, previous disaster losses. These trends can help us to gauge whether disaster risk reduction is being effective. We can also estimate future losses by conducting a risk assessment.

A comprehensive risk assessment considers the full range of potential disaster events and their underlying drivers and uncertainties. It can start with the analysis of historical events as well as incorporating forward-looking perspectives, integrating the anticipated impacts of phenomena that are altering historical trends, such as climate change. In addition, risk assessment may consider rare events that lie outside projections of future hazards but that, based on scientific knowledge, could occur. Anticipating rare events requires a range of information and interdisciplinary findings, along with scenario building and simulations, which can be supplemented by expertise from a wide range of disciplines.

Data on hazards, exposures, vulnerabilities and losses enhance the accuracy of risk assessment, contributing to more effective measures to prevent, prepare for and financially manage disaster risk. Modern approaches to risk assessment include risk modelling, which came into being when computational resources became more powerful and available. Risk models allow us to simulate the outcomes and likelihood of different events.

Risk assessments are produced in order to estimate possible economic, infrastructure, and social impacts arising from a particular hazard or multiple hazards. The components of assessing risk (and the associated losses) include:

- Hazard is defined as the probability of experiencing a certain intensity of hazard (eg. Earthquake, cyclone etc) at a specific location and is usually determined by an historical or user-defined scenario, probabilistic hazard assessment, or other method. Some hazard modules can include secondary perils (such as soil liquefaction or fires caused by earthquakes, or storm surge associated with a cyclone).

- Exposure represents the stock of property and infrastructure exposed to a hazard, and it can include socioeconomic factors.

- Vulnerability accounts for the susceptibility to damage of the assets exposed to the forces generated by the hazard. Fragility and vulnerability functions estimate the damage ratio and consequent loss respectively, and/or the social cost (e.g., number of injured, homeless, and killed) generated by a hazard, according to a specified exposure.

Climate and disaster risks arise due to compounding and cascading hazards and impacts, leading to complex and interconnected adverse consequences for various ecological and human systems. Recent guidance acknowledges that risk assessment and management in the context of climate change requires a comprehensive, systemic perspective on risk and its underlying drivers to the compect and partly systemic nature of climate-related risks.

Ten key principles are proposed for a comprehensive approach for risk assessment and planning:

- Putting risk to human and ecological systems at the centre;

- Fully accounting for the context of climate change;

- Recognizing the complex and systemic nature of risks;

- Applying inclusive risk governance;

- Using multidisciplinary approaches to identify and select measures;

- Using the concept of risk tolerance;

- Addressing, minimising and averting risks through Nature-based Solutions;

- Integrating risk across sectors and levels;

- Strengthening risk communication, information and knowledge sources;

- Using iterative and flexible processes.

Illustration showing phases of a risk assessment, retrieved from Technical guidance on comprehensive risk assessment and planning in the context of climate change, UNDRR (2022).

The technical guidance further provides specific recommendations on how to comprehensively assess risks and reduce and/or address them through planning. It follows the general workflow for risk assessments from International Organization for Standardization standard 31000 with its main phases of scoping, risk identification, risk analysis and risk evaluation:

- A good scoping phase means to design a risk assessment in such a way that it supports decision-making and planning by taking into account existing objectives, goals, values, and the existing policy and planning framework.

- Risk identification aims to identify relevant risks starting from existing knowledge and expert input.

- In risk analysis, the risk components (hazards, exposure and vulnerabilities) and their interlinkages, resulting cascading impacts and the potential for adverse consequences for selected human or ecological systems are explored and analysed using quantitative and qualitative methods.

- Risk evaluation then identifies urgent actions and risk reduction measures based on the levels of risk tolerability defined by the communities and key stakeholders.

Risk can be assessed both deterministically (single or few scenarios) and probabilistically (the likelihood of all possible events). Probabilistic models “complete” historical records by reproducing the physics of the phenomena and recreating the intensity of a large number of synthetic (computer-generated) events. As such, they provide a more comprehensive picture of the full spectrum of future risks than is possible with historical data. While the scientific data and knowledge used for modelling is still incomplete, provided that their inherent uncertainty is recognised, these models can provide guidance on the likely 'order of magnitude' of risks.

Risk models are a representation of reality, but are only as good as the data used.

The convergence of public and private sector risk modelling efforts promises to increase the availability of open access, open source risk information that can be used by business, government, insurance and citizens alike. However, while the experts developing these models clearly understand their limitations, especially at subnational levels, DRR practitioners using the information produced by these models may understand these limitations less well.

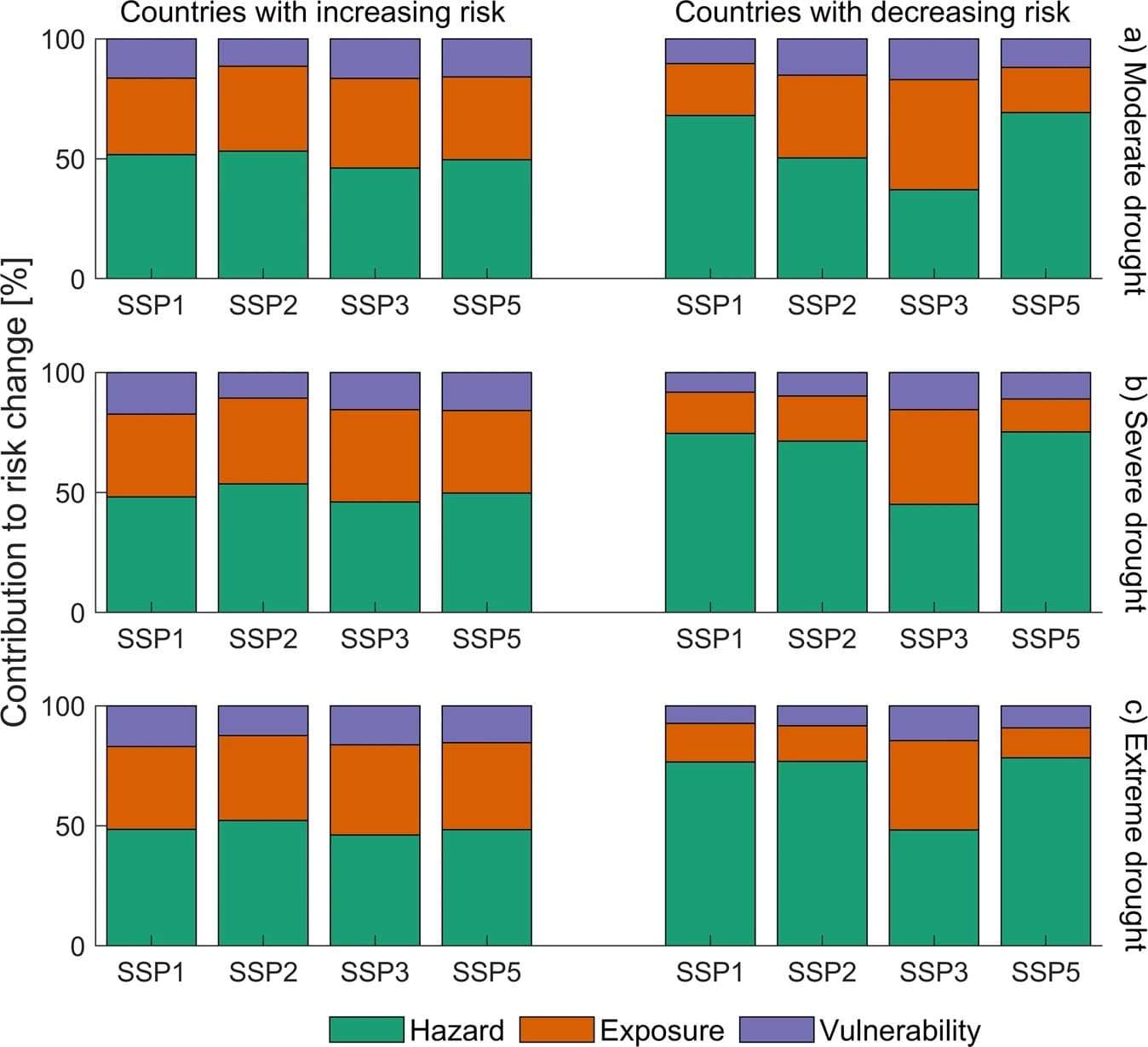

The median contribution across countries with increasing and decreasing risk of moderate (a), severe (b), and extreme (c) droughts is shown. Hazard was calculated for a 12-month scale. Hossein Tabari et al., 2023

The above illustration helps us understand the underlying factors contributing to the substantial increases in drought risk (Hossein Tabari et al., 2023). The study shows that, for both countries with increasing and decreasing risk, hazard was the main driver of risk for all drought extremity levels and future scenarios. On the other hand, the contribution of exposure and vulnerability to future drought risk was generally larger for countries experiencing an increased risk compared to those with a decreasing risk. Overall, this decomposition analysis provides insight into the complex interplay of different factors driving drought risk and highlights the need for tailored approaches to assess the risk and mitigate the impacts of drought in different regions.

Though important challenges remain in assessing risk, more hazard data and models are available; tools and models for identifying, analysing, and managing risk have grown in number and utility; and risk data and tools are increasingly being made freely available to users as part of a larger global trend towards open data. More generally, and in contrast to 2005, today there is a deeper understanding—on the part of governments as well as development institutions—that risk must be managed on an ongoing basis, and that disaster risk management requires many partners working cooperatively and sharing information.

The matrix below is part of a process to assess risk severity of specific hazards. It involves multiplying the likelihood score (1-5) by the impact score (1-5) to obtain a final risk score (1-25) for each hazard. The risk level can then be categorized based on the final score. For more information see here, "Strengthening risk analysis for humanitarian planning".

Illustration: Risk matrix retrieved from Strengthening risk analysis for humanitarian planning, UNDRR (2022).

Risk information provides a critical foundation for managing disaster risk across a wide range of sectors:

- In the insurance sector, the quantification of disaster risk is essential, given that the solvency capital of most non-life insurance companies is strongly influenced by their exposure to catastrophe risk.

- In the construction sector, quantifying the potential risk expected in the lifetime of a building, bridge, or critical facility drives the creation and modification of building codes.

- In the land-use and urban planning sectors, robust analysis of flood risk likewise drives investment in flood protection and possibly effects changes in insurance as well.

- At the community level, an understanding of hazard events—whether from living memory or oral and written histories—can inform and influence decisions on preparedness, including life-saving evacuation procedures and the location of important facilities.

It is well recognized that risk is not static and that it can change very rapidly as a result of evolving hazard, exposure, and vulnerability. Decision makers therefore need to engage today on the risk they face tomorrow. Fortunately, significant new methodologies and data sets are being developed that will increasingly make modelling future risks possible.

How do we reduce disaster risk?

If a country ignores disaster risk and allows risk to accumulate, it is in effect undermining its own future potential for social and economic development. However, if a country invests in disaster risk reduction, over time it can reduce the potential losses it faces, thus freeing up critical resources for development.

Hazards do not have to turn into disasters.

A catastrophic disaster is not the inevitable consequence of a hazard event, and much can be done to reduce the exposure and vulnerability of populations living in areas where natural hazards occur, whether frequently or infrequently. We can prevent future risk, reduce existing risk and support the resilience and societies in the face of risk that cannot be effectively reduced (known as residual risk).

Disaster risk reduction (the policy objective of disaster risk management) contribute to strengthening resilience and therefore to the achievement of sustainable development. Evidence from several countries, including Colombia, Mexico and Nepal indicates that investment in disaster risk reduction is effective - there are therefore both political and economic imperatives to reducing disaster risk. Disaster risk is a shared risk, and businesses, the public sector and civil society all participate in its construction; consequently, disaster risk reduction (DRR) must be considered a shared value. DRR, thus, requires a people-centred and multi-sector approach, building resilience to multiple hazards and creating a culture of prevention and safety.

Disaster risk management (DRM) can be thought of the implementation of DRR and includes building the capacity of a community, organisation or society to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from disasters.

Find out more on specific ways disaster risk can be reduced and managed on our dedicated page on Disaster risk reduction and disaster risk management.

By understanding and managing risk, we can achieve major reductions in disaster losses. For instance, by strengthening their capacities to absorb and recover from disasters, several countries across the world have reduced mortality risk associated with flooding and tropical cyclones. Many high-income countries have also successfully reduced their extensive risks. However, losses associated with extensive risk are trending up in low and middle-income countries.

Last updated on: 04 March 2024