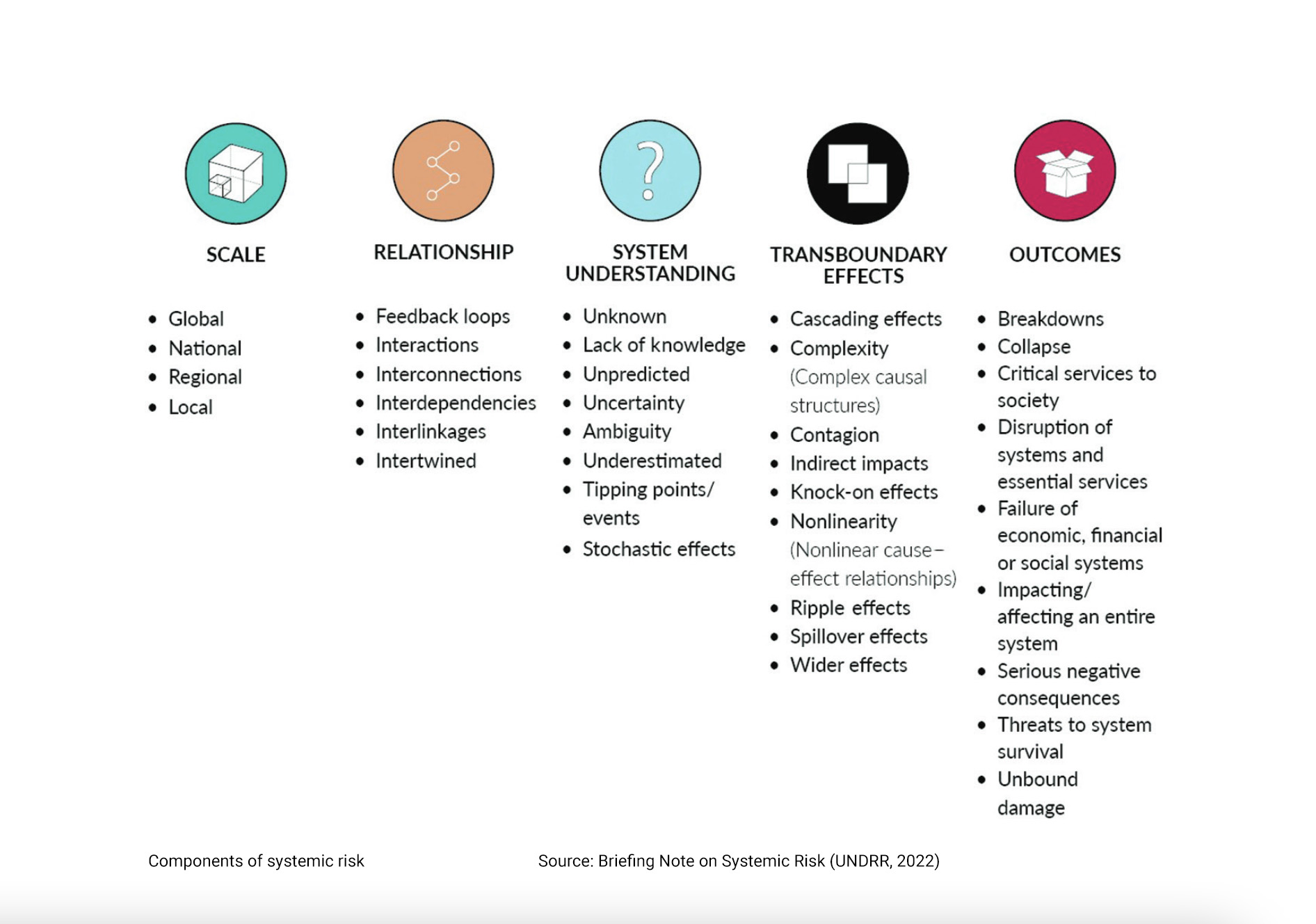

Systemic risk

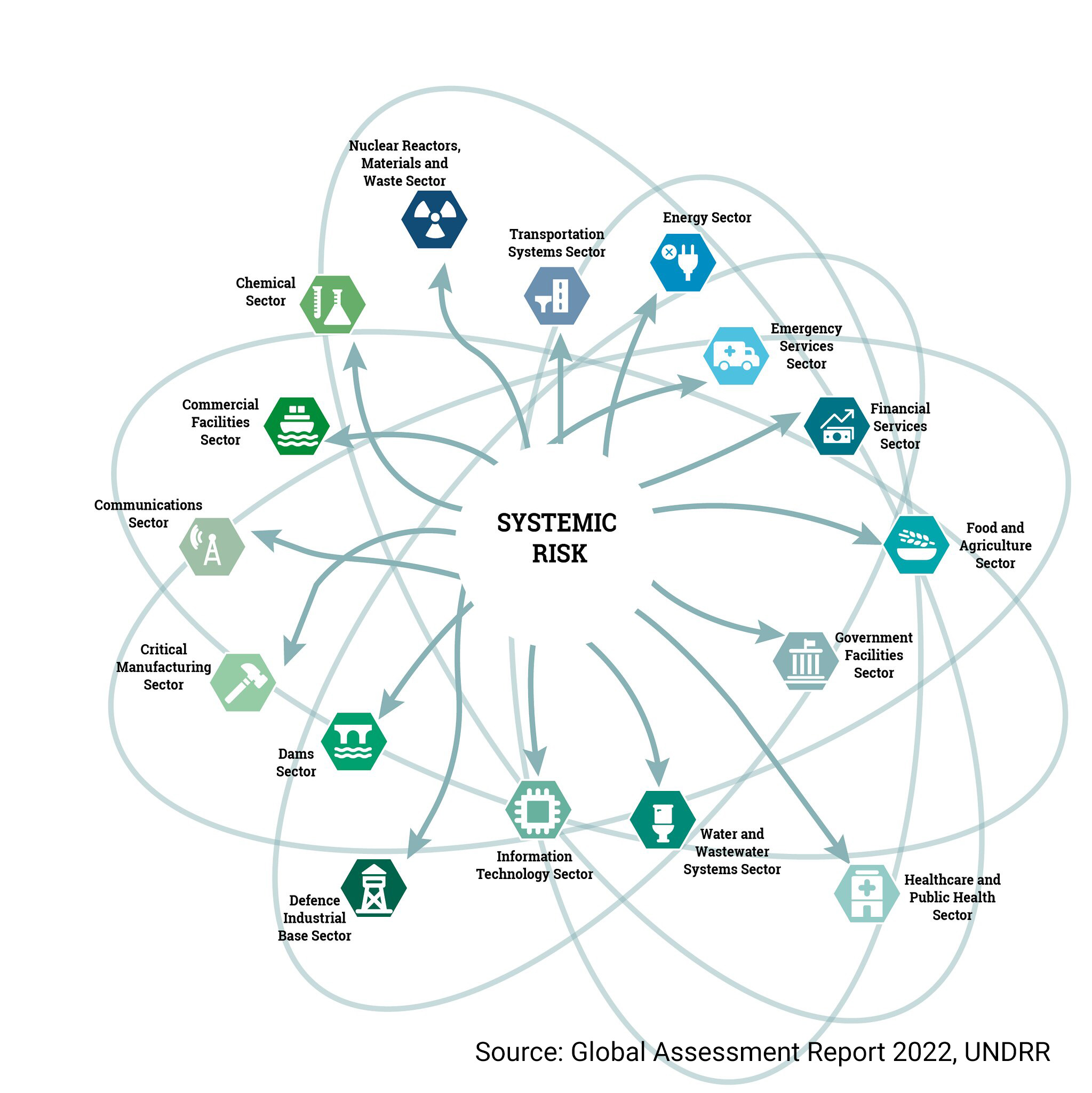

Systemic risk is associated with cascading impacts that spread within and across systems and sectors (e.g. ecosystems, health, infrastructure and the food sector) via the movements of people, goods, capital and information within and across boundaries (e.g. regions, countries and continents). The spread of these impacts can lead to potentially existential consequences and system collapse across a range of time horizons. Globalization contributes to systemic risk affecting people worldwide.

– Briefing Note on Systemic Risk (2022)

Systemic risks involve: multiple communities, cities, regions, or countries; risks that are interconnected; effects that move from one system or network to another and are uncertain or unpredictable; and they have potentially devastating outcomes – like the collapse of entire systems and threats to society as a whole.

Recent disasters that span countries, regions and societal systems have underscored the need for new understanding of the nature of more complex risks, and new approaches to their management.

The COVID-19 pandemic, heatwaves and droughts, volcanic eruptions and tsunamis, wildfires, and conflict and food security crises have all shown clear signs of the rippling effects of hazards and in a globalized world, and the need for systemic approaches to reduce the risks of disasters whose effects resonate across systems and sectors, countries and regions.

Addressing systemic risks requires a new approach, moving from a focus on single hazards, to considering multiple, interdependent hazards and compound hazards, across systems and sectors. This involves working across silos – like climate science, finance, health, and supply chain management – and accepting a greater degree of uncertainty in risk management, and developing multi-hazard early systems.

The global dimension of risk

An interconnected world with a globalized economy has created complex, interconnected risks. Disruptions to food supplies and shipping can have knock-on effects on food security around the world. Climate change creates cascading risks that intersect with non-climatic risks, amplifying the potential for disasters.

Disruptions to global trade and supply chains pose systemic risks that can threaten economic and food security. A single ship getting stuck in the Suez Canal in 2021 caused losses of up to $9 billion per day. Critical transport infrastructure – like roads, ports, canals, railways and airports – are vulnerable to climate-related hazards, especially sea-level rise but also floods, hurricanes and wildfires, and the interaction of infrastructure disruption and other hazards can have devastating impacts.

“As the ripple effects of what are likely to be ever-increasing and intensifying climate-related disruptions spread through the global economy, price increases and shortages of all kinds of goods— from agricultural commodities to cutting-edge electronics— are probable consequences [....] The leap in the cost of shipping a container across the Pacific Ocean as a result of the pandemic — from $2,000 to $15,000 or $20,000 — may suggest what’s in store.”

– Leslie (2022)

Cascading and compound risks

One element of systemic risk is cascading risks – where a hazard can set off a chain of events posing additional, and compounding, risks. Another is compound risks – where two independent hazards co-occur, creating new risks.

“In the really huge fires we had in Australia two years ago, the fires took out the electricity system. So that took out the banking system, so people couldn’t get hold of their money, and it also took out the petrol distribution system… and it took out the mobile phone communication system… so even if people had petrol in their cars they didn’t know where to drive because they didn’t know where the fires were. That’s cascading risk.”

– IPCC author Mark Howden speaking at the 2022 Global Platform on DRR

During the COVID-19 crisis, the risks associated with climate-related hazards around the world have been compounded by additional risks associated with the pandemic. Countries in South and South-East Asia, for example, battled to control the virus alongside droughts, floods and cyclones.

While the COVID-19 pandemic raged on, the region continued to experience other natural hazards, a fair share of which were hydro-meteorological hazards. The lockdowns, travel restrictions and other containment measures imposed as a response to COVID-19 interrupted many established measures for prevention, response, and recovery from natural hazards.

– ESCAP (2022)

In February 2021, in Texas, a coldwave and winter storm prompted systemic failure when the state’s power grid was simultaneously overloaded by high demand for heating while inadequately winterised infrastructure stopped working. The resulting power failures set off a chain of cascading risks affecting fresh water supply, food distribution, health services, and causing over 264 deaths.

Infrastructure is easily understood as a set of connecting elements within a system – for example, power stations connected by power lines that in turn connect to individual households. Infrastructure is in turn interconnected: power, water and sewage services all interact with one another dynamically.... When one service breaks down – or even comes under significant stress – other services are negatively impacted. The failures in Texas began with an electricity demand peak – and led to a breakdown in the supply of basic necessities...

– Bridger (2022)

In early 2022, global food security was threatened by systemic risks involving heatwaves in southern Asia and conflict in Ukraine, severely affecting the availability and cost of grain worldwide.

Heatwaves that struck India early [in 2022] coincided with the critical milking/grain filling stage of wheat crop in mid-March. Consequently, India’s wheat yields were down by 10 per cent to 15 per cent, with the forecasted 2022-23 production dropping from 110 to 99 million tonnes. Food security risks and the sudden spike in global wheat prices due to a shortage in supplies led the Indian government to ban wheat exports to a large extent, with some exceptions to neighboring countries and to support countries to supplement their domestic food security policies. Furthermore, the conflict between Russia and Ukraine has also disrupted wheat exports from the Black Sea region.

– Srivastava, Sarkar-Swaisgood, Dubey et al (2022)

COVID-19

The experience of the COVID-19 pandemic can provide important lessons for the governance of risk going forward in a multi hazard context, and what lessons can be drawn to reduce the impact of the climate emergency.

– Concept Note: COVID-19 and Systemic Risk (UNDRR, 2021)

The COVID-19 pandemic has drawn widespread attention to the systemic nature of risk. The spread of the virus across the world affected all aspects of society – with drastic impacts on employment, international trade, food supply – and this required a cooperative, systemic approach to risk management.

This complexity challenges effective governance and raises the need to shift mechanisms from focusing on single hazards to a multi-hazards and systematic risk approach, in overall prevention, preparedness, response and recovery to emergencies. This is especially true as the effects of climate change become more and more obvious.

– Concept Note: COVID-19 and Systemic Risk (UNDRR, 2021)

A threat to sustainable development

The systemic effects of climatic hazards – like floods, droughts, storms – compounded by non-climatic crises with global reach – like conflict, pandemics, and economic disruption – threaten to steal precious development gains.

Food security in Somalia

In Somalia, nearly 70% of the total population of 15.4 million lives in poverty. Systemic risks include a long-standing history of internal displacement and conflict, which compound food system vulnerabilities from drought and other hazards. The country’s economic recovery was on an upward trajectory in recovering from the 2016 drought until 2018, but the triple shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic, floods and a locust infestation saw a reduced economic outlook by mid-2021. The figure demonstrates the systemic aspects of food security in Somalia and their complexity.

– Source: 2022 Global Assessment Report from Thalheimer et al. (2022)

New approaches are needed

To change course, new approaches are needed. This will require transformations in what governance systems value and how systemic risk is understood and addressed. Doing more of the same will not be enough.

– 2022 Global Assessment Report

UNDRR’s 2022 Global Assessment Report (GAR) calls for a systemic approach to risk governance:

"In the face of global systemic risk, governance systems must quickly evolve and recognize that the challenges for the economy, environment and equality can no longer be separated… systemic risk governance needs to recognize complex causal structures, dynamic evolutions and cascading or compound impacts."

The GAR sets out a 3-point call to action for tackling systemic risks:

- Measure what we value

- Design systems to factor in how human minds make decisions about risk

- Reconfigure governance and financial systems to work across silos and design in consultation with affected people

Last updated on: 12 January 2024