Please help us improve PreventionWeb by taking this brief survey. Your input will allow us to better serve the needs of the DRR community.

Mapping the people, places, and problems of permafrost thaw

By combining demography data with permafrost maps, researchers provide a first count of the population on permafrost and predict its imminent decline.

By J. Besl

Deteriorating apartment blocks. Crumbling runways. Pipes disconnecting as homes dip into the earth. These are just a few concerns residents of the far Northern Hemisphere will face as their ice-rich soils begin to thaw. But how much do these effects matter? That depends on how many people live there.

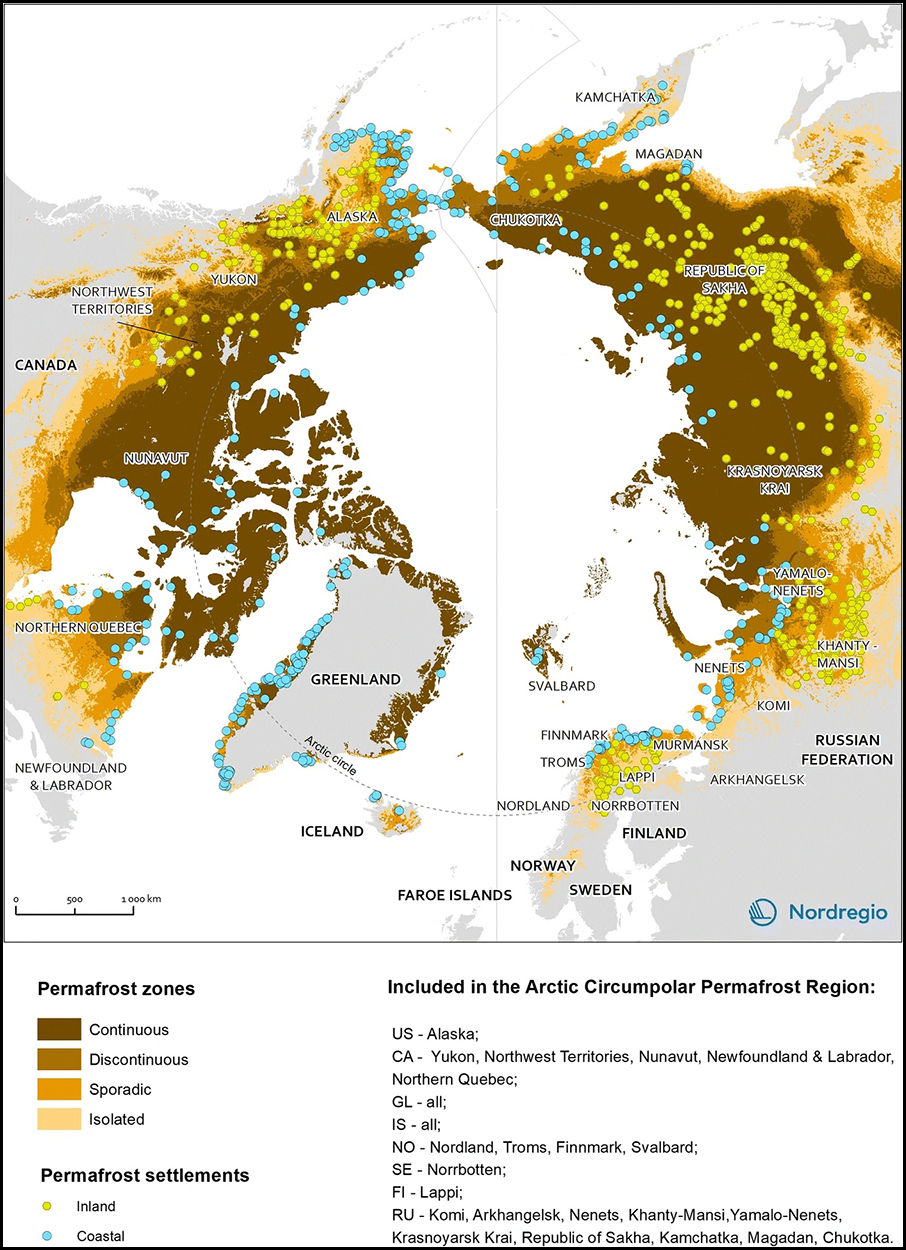

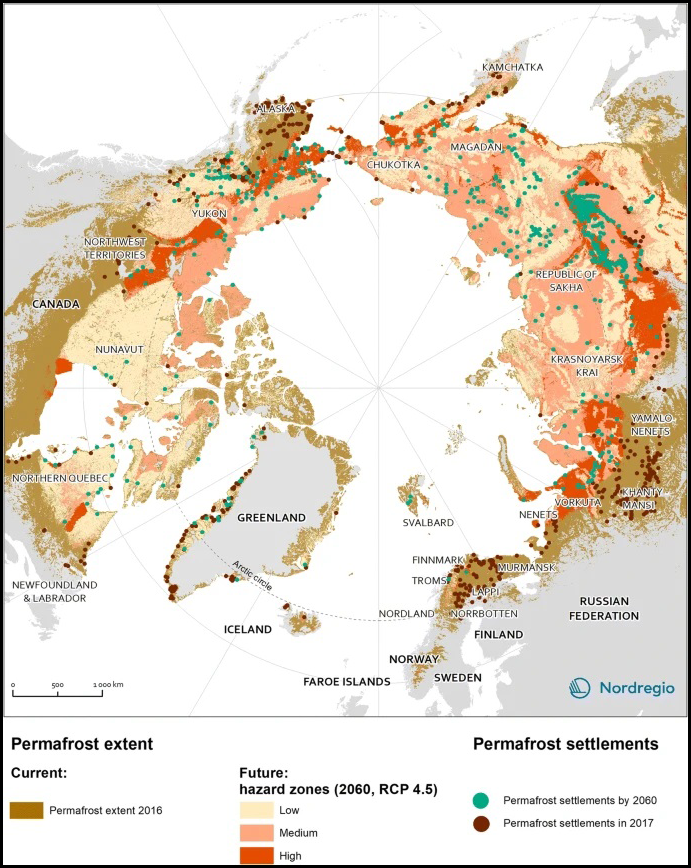

A recent project led by Nordregio, a planning and development research center in Stockholm, combined permafrost maps with census data to identify how many communities and people are located near permafrost. According to the authors, 4.94 million people lived in permafrost areas in 2017. That number could be 1.7 million by 2050 but not because of population loss. The projected 61.2% drop is entirely tied to thawing permafrost.

“Permafrost is a major issue for the global climate. The release of carbon and methane of course has global impact, but [permafrost thaw] also has local impact on the population,” said Justine Ramage, a physical geographer with Nordregio and coauthor of the research, which appeared in Population and Environment in January. By emphasizing the human dimension, she hopes the project raises awareness and spurs communities to plan for change. “The Arctic is warming up, and 2050 is tomorrow, basically,” she said. “It’s within our generation.”

The authors identified 1,162 settlements near permafrost but predict only 628 will remain by 2050. That prediction is based on a Representative Concentration Pathway 4.5 scenario, which assumes carbon emissions will level off in the next few decades.

The risk facing each community depends partly on geology. In Alaska, some soils are 90% ice, meaning the surface could lose 90% of its volume of material. Subsidence is far less likely in Greenland, where towns are generally built near bedrock.

Areas of sporadic permafrost—where anywhere from 0% to 50% of the surface is frozen—were included in the population study.

“Our approach was to think about the consequences in terms of lifestyle,” Ramage said. Maybe your home isn’t on permafrost, she explained, but “if you’re used to hiking or going hunting or picking berries, then this will affect your life.”

Planning Depends on Population

Population plays a role in preparation. The study found most of the region’s residents—4 million people—congregate in just 123 settlements. Larger communities typically have industry, tax bases, and transportation connections to assist in planning. Smaller settlements—which are far more common in the Far North—are generally less connected and more reliant on government assistance.

“It’s good to put more and more specifics on the consequences of changes in permafrost,” said Vladimir Romanovsky, a permafrost researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks not involved in the population research.

The relative impact of the paper may be contextual, Romanovsky noted. For researchers and residents of the North, 5 million is a significant figure. But that number might not resonate in a world of 7 billion.

“I think it’s a great idea. The only thing is, it depends on who’s reading it,” he said.

Cultural Stability

Thawing permafrost also comes with a cultural cost. Consider the sigluaq, or ice cellar. Across northern Alaska, families use these underground vaults dug into the permafrost to cool their subsistence foods. The sigluaq is especially important in Inupiat whaling towns, where one successful hunt provides tons of meat that need to be stored.

Several communities are already seeing water pool and food spoil in their unstable ice cellars. Walk-in freezers are available but are expensive to power and vulnerable to fail in remote communities.

Herman Ahsoak is an Inupiaq whaling captain in Utqiaġvik, Alaska’s northernmost community. For him, the cellar versus freezer debate is about more than energy. Meat stored in permafrost just “tastes 10 times better,” he said. It’s a comment he hears every year at Nalukataq, the midsummer celebration where whaling captains empty their cellars to share maktak, or whale meat, with the community.

Ahsoak’s perspective shows the value of permafrost beyond physical stability.

“People like maktak from the ice cellar,” he said. “When we eat the whale, to me, it fills my mind, body, and spirit because I’ve been eating it pretty much my whole life.”

Explore further

Please note: Content is displayed as last posted by a PreventionWeb community member or editor. The views expressed therein are not necessarily those of UNDRR, PreventionWeb, or its sponsors. See our terms of use

Is this page useful?

Yes No Report an issue on this pageThank you. If you have 2 minutes, we would benefit from additional feedback (link opens in a new window).