Please help us improve PreventionWeb by taking this brief survey. Your input will allow us to better serve the needs of the DRR community.

Using 1980s environmental modeling to mitigate future disasters ー Could the 3/11 disaster have been prevented?

On March 11, 2011, multiple catastrophes in Japan were triggered by the Great East Japan Earthquake, including the nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. This event, also known as the 3/11 disaster, is what is known as a compound disaster. Now that over a decade has passed since this event, researchers are investigating how to prevent the next compound disaster.

Though the 3/11 disaster was an event of unprecedented magnitude, recently published research suggests that this event was not unavoidable and look to an unexpected resource for anticipating compound disasters: 20th century environmental inventories.

The findings were published in peer-reviewed journal Landscape and Urban Planning on Aug 27.

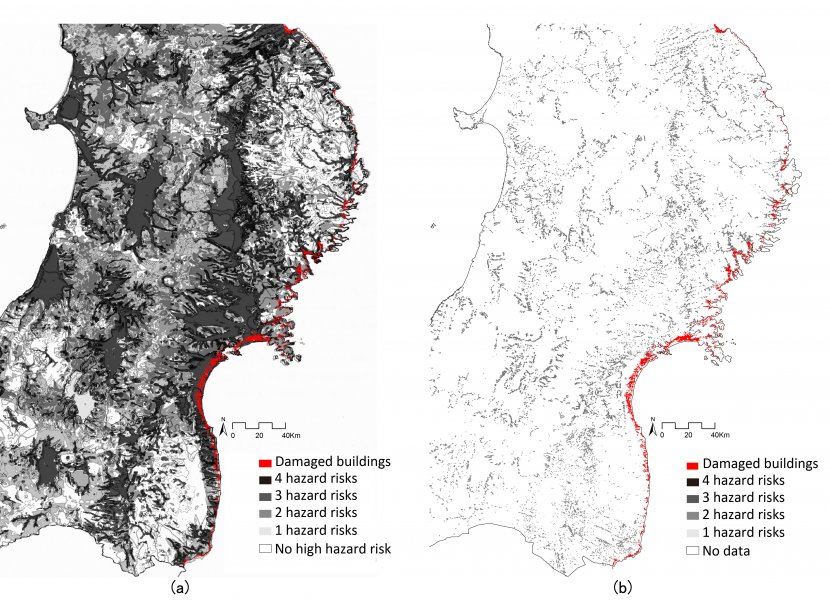

Map overlay of damaged buildings in 2011 with (a) the 1980 JNLA risk map, and (b) the 2019 MLIT risk map: The white area on the 2019 MLIT map is not assessed, hence labeled as “no data”.

“While tremendous efforts have been invested in disaster risk reduction, Japan and many countries continue to see catastrophic events. Effective policies and actions to reduce compound disasters require multi-hazard risk assessment,” said Misato Uehara, an associate professor from the Research Centre for Social Systems at Shinshu University. “This paper proved that by integrating and utilizing findings of 20th century science, such as the 1980 Japan National Land Agency’s (JNLA) environmental inventory, it may have been possible to anticipate recent major disasters.”

Currently, it is much easier to anticipate individual hazards, such as how a hurricane will impact flooding, but this does not necessarily reflect the reality of what happens when there is a major disaster. Major disasters involve large regional areas and individual hazards are interconnected. However, accounting for multiple hazards and how they compound during a major disaster is often inaccessible for governments and organizations because of a lack of information, funding, and the unexpected ways hazards can interact with each other in the real world.

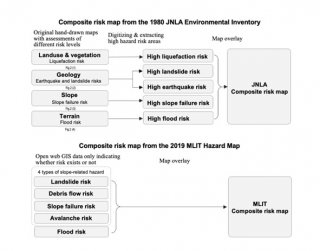

Diagrams showing different processes and contents of the composite risk maps derived from the two data sets: The entire land can be assessed because every environmental characteristic of JNLA maps is assigned a particular risk level. However, the MLIT Hazard Map shows only risks associated with selected environmental conditions.

In this study, researchers looked to ecological planning and the role of an environmental inventory in planning and preventing compound disasters. They used a technique developed by Ian McHarg in 1969 which was described in his book titled Design with Nature. The technique is typically used in ecological planning to determine land use suitability using environmental and cultural criteria. These overlays looked at the risk of possible disasters such as volcanoes, earthquakes, mudslides, and flooding.

Researchers theorized that the risk assessment by different environmental classification maps in the same area could predict the locations where compounding disasters would be the most destructive. “By using this theory, risk assessment of any location is possible. Despite advancements in hazard knowledge and risk modelling since 1980, recent hazard maps still present very limited risk information,” said Uehara. While this technique has been widely used in environmental planning and landscape architecture, it is not a standard practice in disaster risk mitigation. Most of the existing research into applying this technique to hazard risk assessment has looked at single hazard risks instead of multiple.

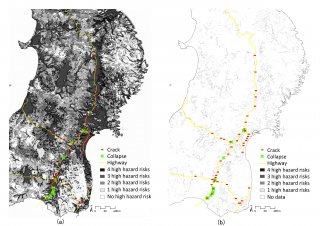

Map overlay of damaged highway sites in 2011 with (a) the 1980 JNLA risk map, and (b) the 2019 MLIT risk map: The white area on the 2019 MLIT map is not assessed, hence labeled as “no data”.

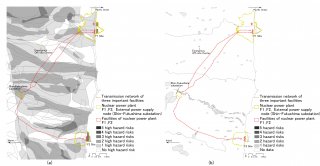

To prove the technique’s viability, researchers compared 1980 composite risk maps from the Japan National Land Agency over maps showing the damage from the Great East Japan Earthquake and compared them to 2019 hazard maps from the Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Of the 60 damaged highway sites, 89% were considered to have one or more high hazard risks according to the 1980 JNLA map. Only 8.4% of the damaged highways were noted on the 2019 MLIT map. Similarly, 81% of the sites for the Fukushima Nuclear Plant, including both plants, the substation, and the emergency site, were considered high hazard risks in the JNLA map. Even after the 2011 disaster, 0% of these locations were noted as high risk in the 2019 MLIT map.

Map overlay of the damaged Fukushima nuclear facilities in 2011 with (a) the 1980 JNLA risk map and (b) the 2019 MLIT risk map: The white area on the 2019 MLIT map is not assessed, hence labeled as “no data”.

Looking ahead, researchers are planning how to continue to evolve complex risk assessments that involve multiple hazards. “Research will continue into the possibility of assessing the risk of an entire region based on the characteristics of environmental classifications as opposed to risk assessment, which involves advanced computational simulation to limit the scope of assessment and natural conditions,” said Uehara. “Governments and organizations without necessary resources for advanced risk modeling could benefit from conducting such relatively simple and inexpensive multi-hazard risk assessment to reduce compound disasters.”

Other contributors include Kuei-Hsien Liao of the Graduate Institute of Urban Planning at National Taipei University, Yuki Arai of the Faculty of Humanities at Matsuyama University, and Yuta Masakane of the Faculty of Agriculture at Shinshu University.

The 2021 Japan Prize Heisei Memorial Research Grant, the JST, and the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature supported this research.

Explore further

Please note: Content is displayed as last posted by a PreventionWeb community member or editor. The views expressed therein are not necessarily those of UNDRR, PreventionWeb, or its sponsors. See our terms of use

Is this page useful?

Yes No Report an issue on this pageThank you. If you have 2 minutes, we would benefit from additional feedback (link opens in a new window).