Please help us improve PreventionWeb by taking this brief survey. Your input will allow us to better serve the needs of the DRR community.

Wildfire threats not commonly disclosed by U.S. firms despite risk to economy

Public companies bury such risks, UC Davis researchers suggest.

Wildfires in the United States, especially in Western states, increasingly pose a significant risk to entire communities, often destroying homes, businesses and lives. When wildfires sweep through a region they also affect the economy as a whole, decreasing U.S. firms’ values to stockholders when businesses incur physical damage, cause or experience supply chain issues, or lose employees.

Yet U.S. firms rarely report their wildfire risks in required federal filings and instead bury such risks in nonspecific risk disclosures, according to new research led by the University of California, Davis.

The study was published this month in the Journal of Business Finance & Accounting.

On average, only 6.1% of firms with wildfires in their headquarters county mention wildfire information in their required disclosures and exhibits filed with the Security and Exchange Commission, according to the study. The disclosures and exhibits are included in annual reports known as 10-Ks, which are filed by all publicly traded companies. These required disclosures are key to company valuations and can reveal the company’s current and future financial conditions.

“Despite a growing awareness of the strategic importance of climate change, firm-level disclosures of extreme weather and climate-related risks and events remain the exception rather than the norm,” said Paul Griffin, professor at the UC Davis Graduate School of Management and lead author of the paper. He is an authority on accounting and financial information and disclosure, particularly in relation to extreme weather and climate change.

“Disclosure is a sign that the firm is taking these events seriously and will take action itself to mitigate the risk,” Griffin explained. “Disclosure leads to real action.” And companies that disclose risks can be viewed as less risky to investors, he said.

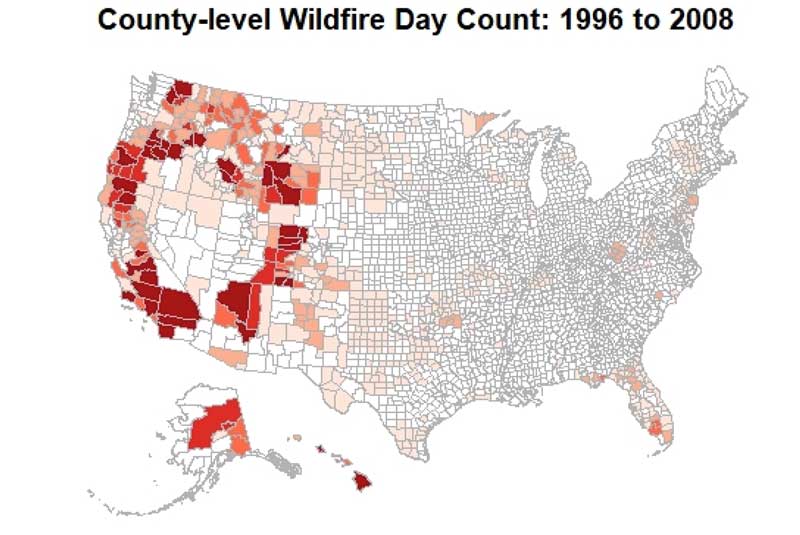

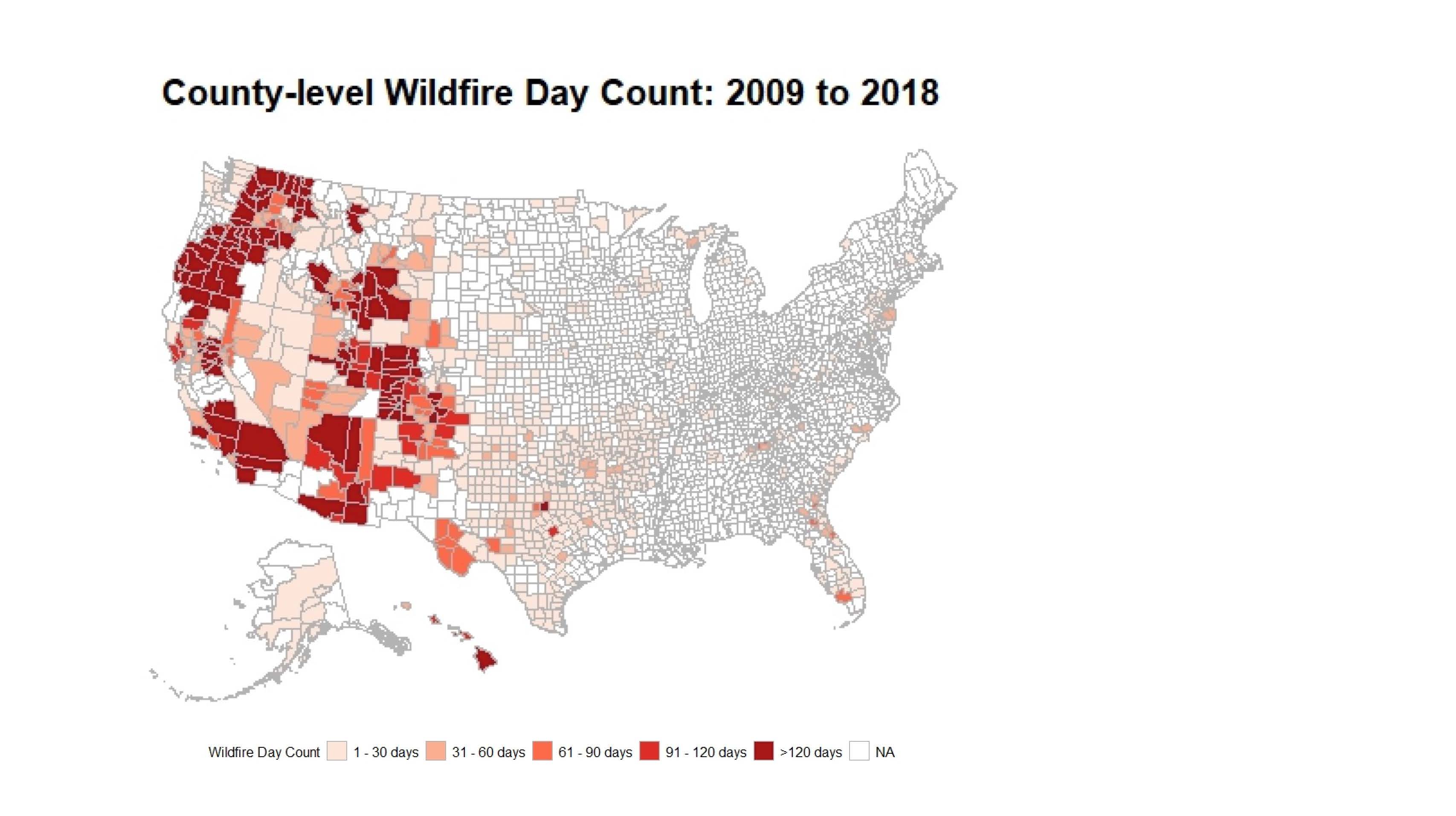

The researchers looked at more than 80,000 10-K reports between 1996 and 2018 to see if those reports contained disclosures about wildfire events that occurred during the same period.

Griffin said he and his coauthors were encouraged that they could identify firms that were being sensitive to wildfires in their region — but highly discouraged that so few report these risks and take action to begin mitigating the risks. Firms can, for example, consider moving their operations to less fire-prone areas, make improvements in current buildings and equipment, develop fire safety strategies for employees, or establish other mitigation plans.

Wildfire days in firm’s county

Researchers found that the number of wildfire days in a company's headquarters county is a key determinant of whether that company will disclose wildfire risk. For the most part, only firms previously affected by wildfires in their counties — mostly utility and banking industries with tangible assets — report those risks. One example was PG&E, a public utility in California, which has been held responsible for wildfires due to equipment failure. However, PG&E reported their potential risk to wildfire only after their risks and liability were publicly disclosed — a common issue with many disclosure statements the researchers reviewed. Griffin said even when already exposed, they disclosed very little about their future potential risks, which is also necessary in a situation when there is ongoing risk.

Researchers said the most disclosure-sensitive firms are those that likely experienced wildfire events affecting their past operations, whereas the most disclosure-insensitive firms are those whose 10-K disclosures relate to forward-looking risk factors only. These latter firms are also likelier to use limited imprecise language to describe their wildfire risk, they said.

Researchers found that wildfire disclosure sensitivity increased around and after 2010, consistent with the SEC guidance pressing firms to consider extreme weather as a material risk factor.

Paper co-authors include Yijing Jiang and Estelle Sun, both of Boston University Questrom School of Business.

Explore further

Please note: Content is displayed as last posted by a PreventionWeb community member or editor. The views expressed therein are not necessarily those of UNDRR, PreventionWeb, or its sponsors. See our terms of use

Is this page useful?

Yes No Report an issue on this pageThank you. If you have 2 minutes, we would benefit from additional feedback (link opens in a new window).