Building a more resilient Afghanistan

By Federica Ranghieri and Ankur Nagar

Imagine you live in Afghanistan. There’s a 7 in 10 chance that your livelihood depends on agriculture. In this mountainous country, with mean elevation of 1,884 meters (higher than Chile), it is likely that your farm is in a river valley surrounded by a rugged landscape.

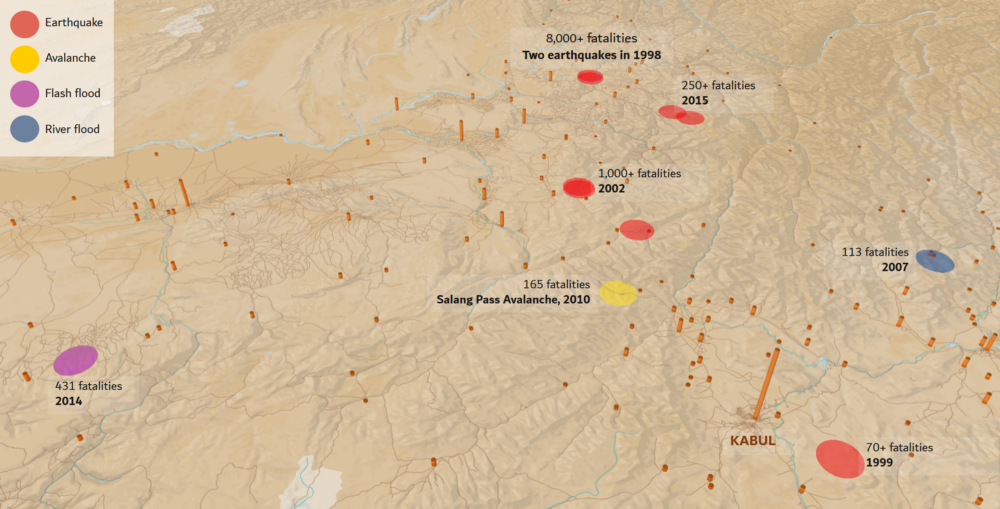

Here, you may have experienced an earthquake. Since 1998, more than 190 earthquakes of magnitude 5+ have hit Afghanistan, and killed over 10,000. Your daughter, like one in every two children, studies in a temporary shelter. If an earthquake hits during school time, 5 million students can be exposed.

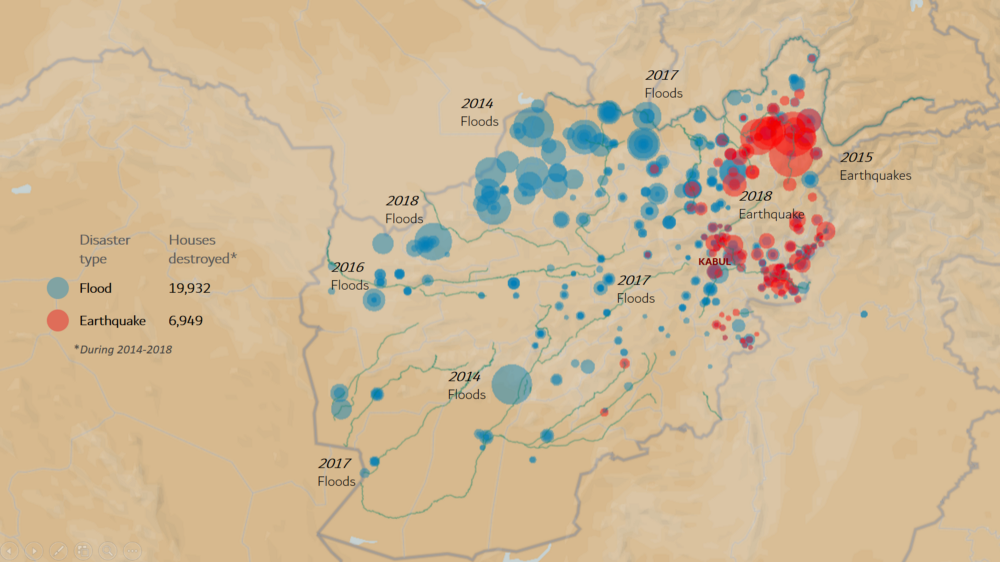

Houses destroyed by floods and earthquakes: 2014 to 2018

In winter, over 1,000 millimeters of snow falls over the country’s mountains. The melt of this snow-pack flows through mountain streams and feeds your farm. It also runs the nearby hydropower plant. When it’s warmer than average, snow melts rapidly and the steep slopes cause frequent floods.

In this terrain, intense rainfall also leads to flash floods, especially in cities. Just in 2018, these have claimed over 30 lives. Every year floods cause an average of US$ 54 million in damages. Climate change is a worry too — it can double the number of Afghans affected by floods by 2050.

On the other hand, droughts are also a reality. Since 2000, these have affected 6.5 million people. In 2018, about 275,000 people have been displaced by drought in western and northern Afghanistan, 52,000 more than the number uprooted by conflict — over two million are threatened by water shortages.

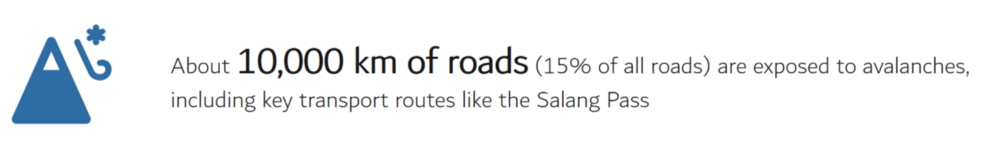

In this landlocked country, you travel by road to sell your produce at the main markets, such as in Kabul, Jalalabad, or Kandahar. The Salang highway that you take crosses treacherous icy passes through the Hindukush mountains and reaches elevations of 3,400 meters. Landslides and avalanches have killed hundreds on the highway over the last several decades.

Deadly disasters around Kabul, 1998–2018

A sobering scenario. It reflects the fact that within low-income countries Afghanistan is second, surpassed only by Haiti, in the number of fatalities from natural disasters during 1980–2015. Its low levels of economic development also make it extremely vulnerable to impacts of climate change.

Generating and sharing critical risk information

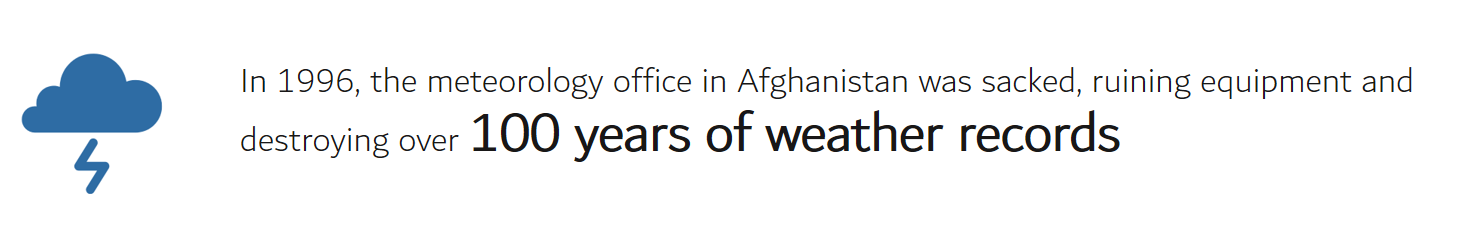

Decades of conflict have undermined Afghanistan’s coping mechanisms and protective capacity. A lack of risk and weather information has reversed years of development, exacerbated natural disasters, and caused accidents. Availability of risk information is key for this country, where reconstruction after natural disasters and conflicts is on-going.

Since 2015, Afghanistan has begun laying the building blocks for resilience. In a first-of-its-kind effort for a fragile state, the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR), the World Bank, the Government of Japan, and the Afghanistan National Disaster Management Agency have worked in close collaboration on the Establishing Critical Risk Information project.

Despite restrictions on fieldwork due to a lack of national security, the project collected and analyzed risk information with help from the Afghanistan Government, NATO’s Resolute Support, the World Bank, and other development partners — and through satellite observations, global datasets, and modeling tools.

What does this critical risk information tell us? Here are some examples:

The Afghanistan Disaster Risk Profile summarizes and visualizes the essential information needed to understand the current and future risk from:

- Floods

- Earthquakes

- Droughts

- Landslides

- Avalanches

The results and geospatial layers from this risk profile are shared as open data at the Afghanistan Disaster Risk GeoNode, which contains both locally developed datasets and globally derived data such as elevation models.

Developed by a consortium of specialist organizations, the comprehensive Afghanistan Multi-Hazard Risk Assessment includes:

- In-depth analysis of natural hazards and disaster risk in Afghanistan, including: fluvial and flash floods, droughts, landslides, snow avalanches, and seismic hazards

- A first-order analysis of the costs and benefits of resilient reconstruction and risk reduction strategies

- Design recommendations to implement short- and long-term measures and build structures to mitigate disaster risk

The Strengthening Hydromet and Early Warning Services in Afghanistan: A Road Map first identifies challenges in the production and delivery of weather, climate, and hydrological information and associated services.

Next, it proposes a strategic technical framework for improving the hydromet and early warning services — and the resulting socioeconomic benefits.

It also lays out a pathway with achievable milestones for three investment scenarios — based on realistic fiscal and sociopolitical possibilities — for better delivering these services.

Back in the shoes of an Afghan, you might wonder how this information can reduce risk for your family and your livelihood. Could it help make schools safe from earthquakes? How about making hydropower plants safer? What about avalanche risk on the Salang Pass?

Using critical risk information to build back better

Renewed access to critical risk information is helping the Afghanistan Government to mainstream disaster and climate considerations into their budget and planning processes for reconstruction.

To develop this capacity, the Establishing Critical Risk Information project (ECRI) has provided training in disaster management concepts and the use of risk information to: the Afghanistan National Disaster Management Agency (ANDMA), the Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development (MRRD), the Meteorological Department, Kabul Municipality, and others. In turn, MRRD has trained over 4,500 communities in disaster risk management.

As the capacity within the government scales, to make the most of existing resources the World Bank has also focused on leveraging the critical risk information across several key sectors in its investment — including transport, education, energy, and social protection.

Under the Trans-Hindukush Road Connectivity Project, risk information has enabled an assessment of landslide and avalanche risk along two highly vulnerable corridors: the Salang Pass and the Baghlan to Bamyan highway. This has provided policy makers with a Transportation Geohazard Decision Support System to identify vulnerabilities and select mitigation measures.

Critical risk information is also helping the Afghanistan Rural Access Project to identify locations where natural hazards threaten the all-seasonality of road network, and to implement design strengthening and maintenance improvements to mitigate risks.

Education: Making schools resilient to natural hazards

ECRI and the Global Program for Safer Schools have supported an assessment of the vulnerability of school infrastructure in Afghanistan, including recommendations for new construction and retrofitting of existing schools. It’s estimated that retrofitting schools for earthquakes across the country can reduce economic losses by 60 percent and reduce fatalities by 90 percent.

This assessment informed the ongoing EQRA project, which supports the implementation of Afghanistan’s National Education Strategic Plan. The plan aims to reach 100 percent enrollment by building 20,000 new schools.

Energy: Making energy supply resilient to climate and disasters

Climate and natural hazards can have catastrophic impacts on Afghanistan’s energy system. The electricity grid is vulnerable to natural hazards, and hydropower is vulnerable to climate change because of the risk of recurrent droughts. Fuel imports, which rely on road transport, are also at risk.

Critical risk information is essential for the design of a disaster risk management framework for the energy sector in Afghanistan. Risk information has also supported an analysis of renewable energy, both off-grid and large scale, to reduce reliance on vulnerable infrastructure and build climate resilience. The findings can be incorporated into World Bank’ energy projects, such as the Naghlu Hydropower Rehabilitation Project.

Social protection: Building community capacity for resilience

Under the Citizens’ Charter Afghanistan Project, risk information has helped train rural communities in infrastructure resilience principles, hazard-vulnerability analysis, and community mapping. This helps them to prioritize resilience investments, such as protection walls, clinics, and canals.

Training government officials and engineers in risk information tools — including the GeoNode platform — has enabled them to work with the Community Development Councils to screen prioritized infrastructure for associated disaster and climate risks.

Critical risk information also helps in the assessment of new irrigation schemes and dams under the Irrigation Restoration and Development Project, which supports irrigation rehabilitation of more than 300,000 hectares. The Government of Japan has also supported flood resilient irrigation and dam safety in Afghanistan by providing technical support to the Ministry of Energy and Water and by organizing a Technical Knowledge Exchange on Dam Safety.