|

Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2015

Making development sustainable: The future of disaster risk management |

|

Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2015

Making development sustainable: The future of disaster risk management |

|

|

125

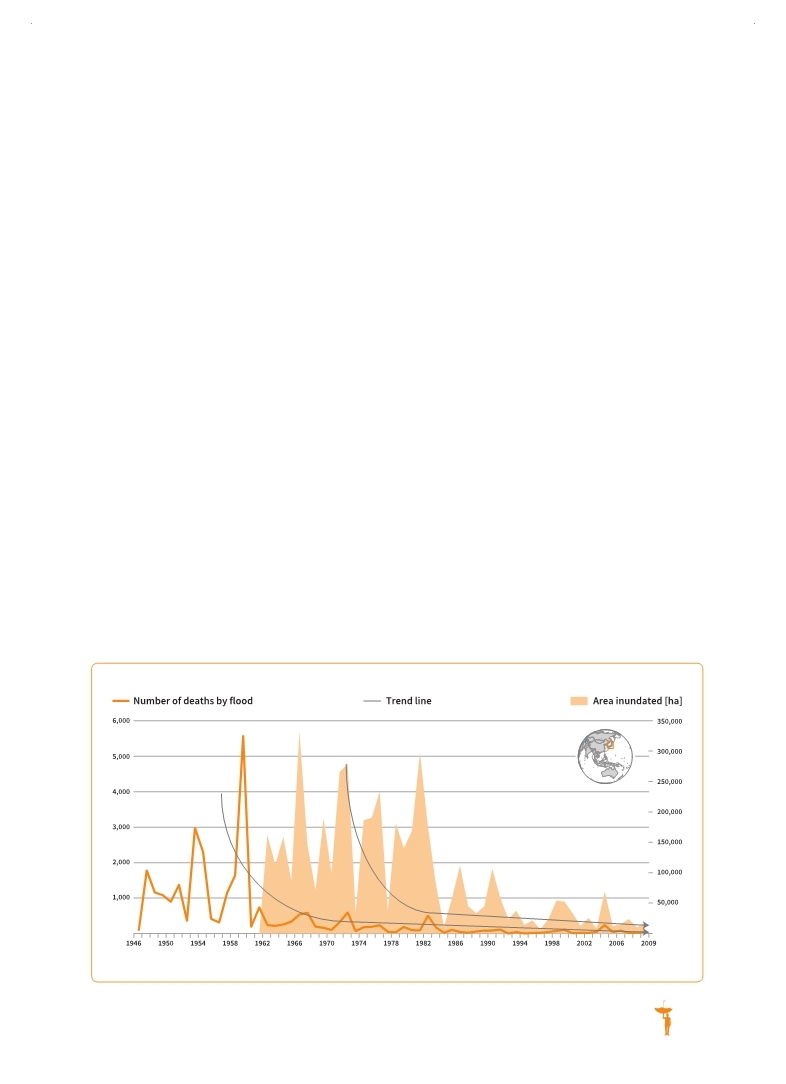

extensive risk layers. In Japan, for example, continued investment in flood protection—together with regulation—has resulted in a dramatic reduction in the areas flooded and in mortality (Figure 6.3).

In contrast, many low and middle-income countries lack the necessary regulatory quality for norms and standards to be applied effectively. In many such countries, weak accountability of local to central government, of government to citizens, and across government sectors has undermined the effectiveness of norms, standards, laws and policies (

Coskun, 2013 Coskun, 2013 Coskun, Arife. 2013,The expansion of accountability framework and the contribution of supreme audit institutions, Input Paper prepared for the 2015 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.. Coskun, Arife. 2013,The expansion of accountability framework and the contribution of supreme audit institutions, Input Paper prepared for the 2015 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.. Click here to view this GAR paper. IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies) and UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2014,Effective law and regulation for disaster risk reduction: a multi-country report, New York.. . As a consequence, the adoption of improved building codes or environmental regulations in lower-income countries may lay a veneer of disaster risk management over the surface of relentless risk accumulation (Wamsler, 2006

Wamsler, Christine. 2006,Mainstreaming Risk Reduction in Urban Planning and Housing: A Challenge for International Aid Organisations, Disasters, Vol. 30, No. 2: 151-177.. . particular, where a significant proportion of economic and urban development takes place informally (either in an informal sector per se or due to corruption and lack of compliance in the formal sector), instruments such as building codes and zoning plans are only effective in strictly limited areas and sectors, typically in higher-income enclaves and strategic economic sectors. Most building outside of these enclaves and sectors is non-engineered, most urbanization is unplanned and local governments have weak capacities to promote or enforce standards.

In addition, the adoption of inappropriately strict codes and standards may have the opposite effect of driving more development into the informal sector, as low-income households and small businesses are unable to afford the costs of building to code in areas zoned for residential or commercial use.

Finally, the responsibility of those taking the decisions with regard to urban development, the application of building codes or land-use planning is not always clear-cut, as seen in the legal

(Source: UNISDR with data from Takyea Kimio, JICA.)

Figure 6.3 Successful flood reduction in Japan

|

Page 1Page 10Page 20Page 30Page 40Page 50Page 60Page 70Page 80Page 90Page 100Page 110Page 115Page 116Page 117Page 118Page 119Page 120Page 121Page 122Page 123Page 124Page 125Page 126->Page 127Page 128Page 129Page 130Page 131Page 132Page 133Page 134Page 135Page 136Page 137Page 138Page 139Page 140Page 150Page 160Page 170Page 180Page 190Page 200Page 210Page 220Page 230Page 240Page 250Page 260Page 270Page 280Page 290Page 300Page 310

|

|

|

|