Even when most of California is dry doesn’t mean we can’t have floods

Every water year is different in California, and in any water year, local and regional experiences often differ. California is a large state, far larger than most storm systems and atmospheric rivers with large topographic differences, so some parts of California are usually wetter or drier than others. Part of the rationale for California’s inter-regional water projects was to help average out geographic variability in water availability using canals, in addition to water storage which helps average water availability over time. This post examines how different parts of California often see very different water years.

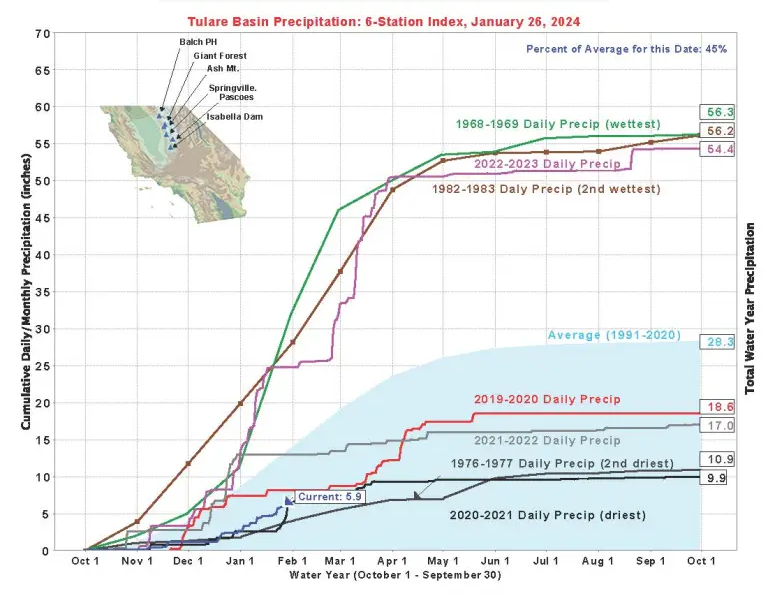

Last water year (2023) illustrates how different parts of California often experience substantially different hydrology. Although 2023 was among the wettest on record for the Tulare Basin, it was only middling-wet for the Sacramento Valley (but still wet enough to fill almost all its reservoirs).

Regional conditions often differ from statewide averages

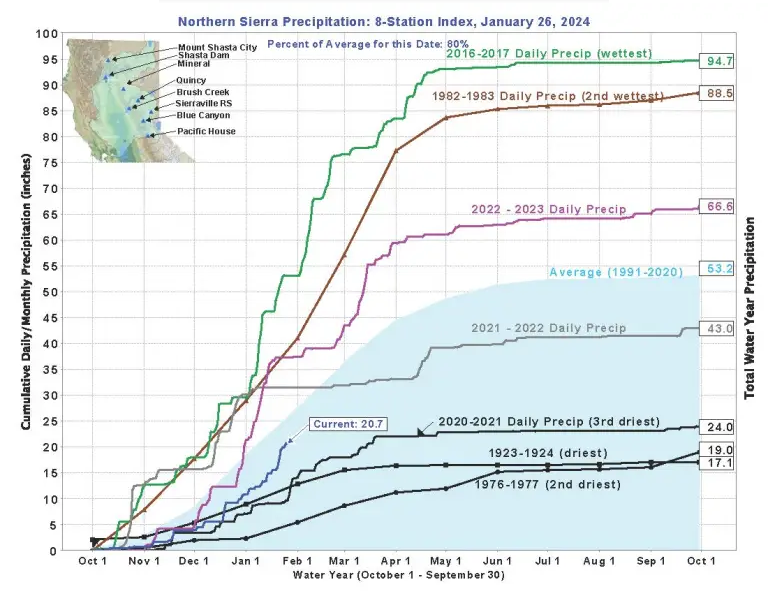

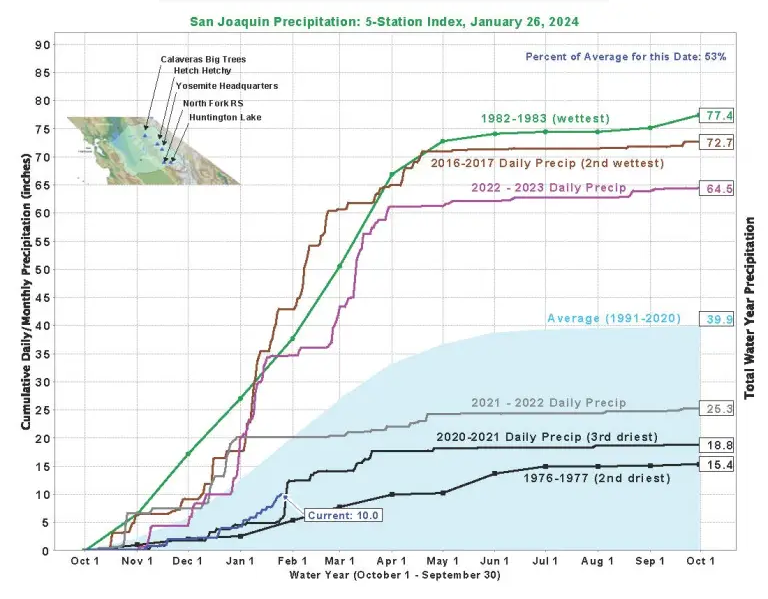

The three figures below show standard DWR plots of cumulative precipitation for the Norther Sierra (Sacramento), San Joaquin, and Tulare precipitation indices.

A – Sacramento Basin

B – San Joaquin Basin

C – Tulare Basin

2023 was in the fourth wettest water year on record for the Tulare basin (going back to 1922: 1969, 1983, 1998, and 2023). Yet, for the Northern Sierras, 2023 was only the 18th wettest water year over the same period. Indeed, Trinity Reservoir, in the Klamath basin, was almost the only reservoir in California that did not entirely refill in 2023. These plots also show that 2023 was not unique in each region having a somewhat different experience. The wettest years in the different basins often occur in different years. Local and regional experiences often vary.

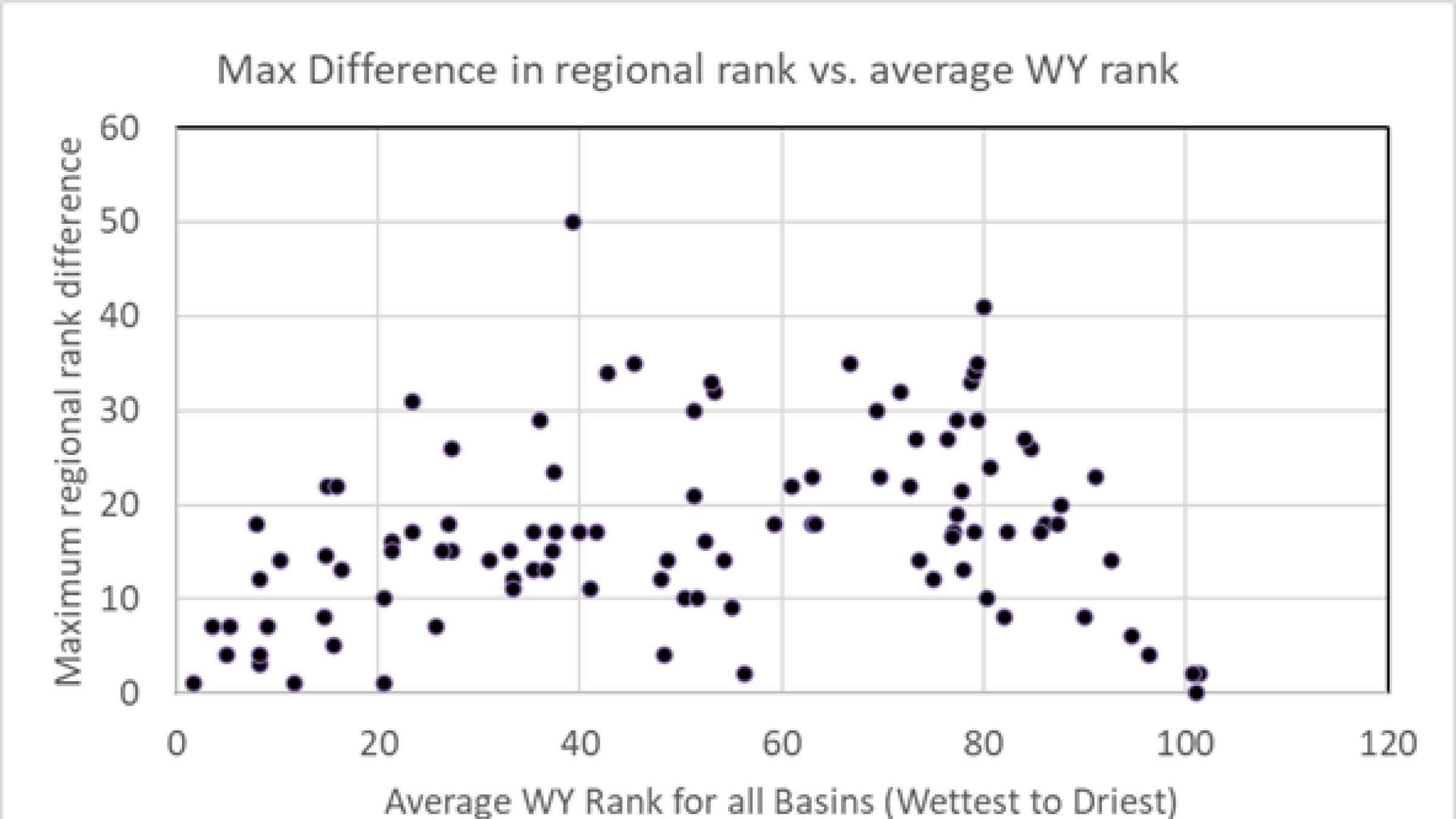

Looking at these precipitation statistics since 1922, although regions tend to be wetter or drier together, there are sizable differences. The figure below plots the maximum difference between each region’s water year rank (1 = wettest) and the average rank across all three regions. The driest and wettest years overall tend to be more similar across regions. (Largely, this is because ranking very wet or dry statewide requires it to be at least pretty wet or dry everywhere.) For example, WY 1977 is the driest for all three basins (and statewide). WY 1983 and 2017, the wettest years of record statewide, tend to be very wet everywhere. The middling years overall are more likely to have divergent regional water availability.

Local conditions often vary from regional conditions

Regional experiences often differ from statewide averages. Local experiences can differ by much more. Just because most of the state has below average precipitation doesn’t mean that California can’t have flooding.

This dryish year (so far overall) has brought one of San Diego’s biggest floods, as covered recently in the media. While there was considerable urban property damage, fortunately no one seems to have died. Even in dry years, we must be prepared for floods, especially local floods.

In 2023, a wet year overall, there was little regional flooding, but serious local flooding with sizable property damages and deaths.

Implications

Some implications of California’s local and regional variability in hydrology are:

- Water management should always be substantially local. This is true for more than hydrologic variability, of course. Most adaptability and preparations must be arranged, implemented, and financed locally for many reasons.

- Some state policies have broad applicability and relevance, such as plumbing codes. State policies are especially important where they support local adaptability, such as those on governance, safety, accountability, and finance. But many potential statewide policies and management will have limits and inefficiencies for local conditions.

- Averaging regional variations in water availability can be dampened somewhat using inter-regional water conveyance and storage. Yet, even where infrastructure exists to move water among regions and localities, a host of financial, economic, policy, environmental and operational issues remain.

- Even in dry years, California must be prepared for floods.