Oriental Institute restores ancient Egyptian monuments threatened by climate change

Institute led dismantling and reconstruction of three monumental gates in danger of collapse

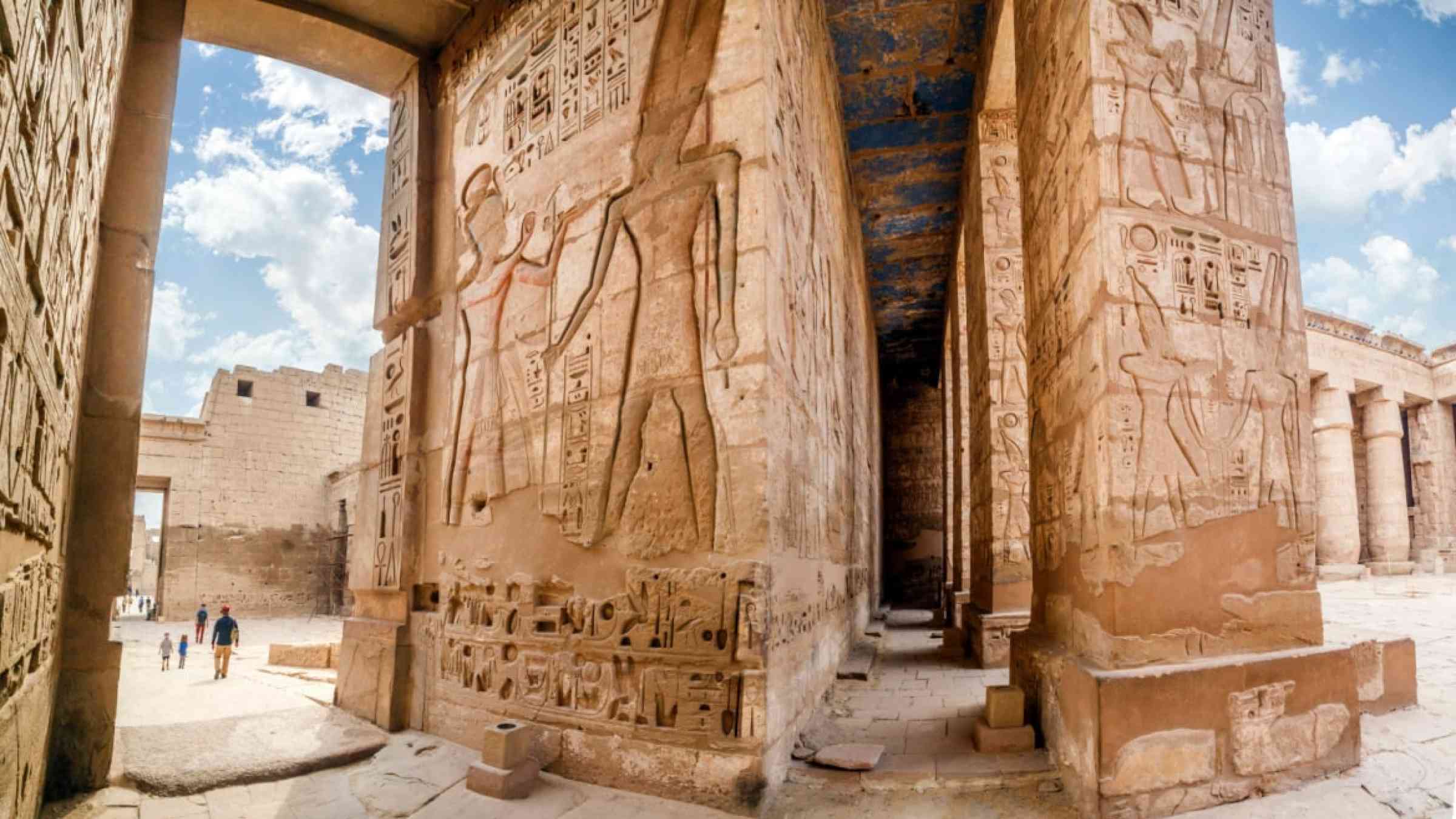

The ancient temple complex Medinet Habu has survived for thousands of years in the arid desert climate. But in the 100 years since the Oriental Institute’s (OI) Epigraphic Survey first arrived in nearby Luxor, Egypt, things have changed. Temple floors have become muddier, salt crystals have formed on stone monuments and ancient foundations have slowly turned back into sand.

Egyptologist Brett McClain has been part of the Epigraphic Survey since 1998. Each year from April to October, the Survey’s team members return to the Chicago House in Luxor to record inscriptions found on nearby ancient sites.

Every year researchers find more evidence of a looming threat faced by these historical monuments: climate change.

“By the 1990s, we were really beginning to see the effects of the environmental transformation of Egypt,” said McClain, the Survey’s interim director. “We realized that it was our responsibility to the monuments that we were working on not just to record them, but to restore and preserve them physically.”

The team hopes to mitigate damage caused by a combination of human intervention and climate change. With the aid of grant funding from USAID Egypt, the OI has led the restoration of three free-standing structures in Medinet Habu that were in danger of collapse. Restoration of the first gate was completed in 2017, while two other monuments will be completed this spring.

A changing landscape

Built in the 1960s, the Aswan Dam, south of Luxor, allowed farmers to cultivate crops year-round rather than depending on the natural flood and drought cycle of the Nile River. However, the constant irrigation needed to sustain these crops has led to a change in the water levels in areas along the Nile—including Medinet Habu.

In addition to local dam and irrigation projects, the effects of global climate change have hit Egypt particularly hard.

“Since I started coming in the late ’90s, we’ve seen higher levels of humidity in the atmosphere and more frequent rainstorms,” said McClain. “That extra water, that extra humidity, is terrible for the ancient monuments.”

More water spells danger, but the true enemy of preservation is salt—as any pothole-plagued Chicagoan can attest. The salt found in groundwater causes cracking and eats away at the stones.

The smaller Claudius Gate (41-54 A.D.) before restoration. The Roman-era monument to Emperor Claudius marks a sacred route for festival processions.

Photo courtesy of the OI

“It's always the bottom of the stone wall that is the most severely affected,” McClain said. “So you have enormous monuments made of stone, and the part that's deteriorating is right at the foundation—the part that supports all the weight.”

This is especially true of the many free-standing structures found in Medinet Habu—a complex that encloses several temples built over a long period of time into a single sacred site. The main, central monument was built during the reign of Rameses III, one of the last great Pharaohs of the New Kingdom.

The site also includes dozens of stone gates, which demarcate one important part of the complex from another. Three of these gates were at serious risk of structural collapse and were prime candidates for restoration efforts.

Block by block

A serious risk requires a serious intervention. The Survey team’s plan was to dismantle each gate, block by block, and rebuild it in its original place.

“Dismantling a structure completely and rebuilding it is the last resort, because it's very impactful,” McClain said. “This is something that we do because the alternative is complete collapse.”

Such a big undertaking takes a big team—up to 100 people altogether, according to McClain. Several stone workers carefully dismantling each block, which was then passed along to a team of conservators for treatment. Then, workers laid a new foundation before the process happened in reverse, with each stone returning to its original place.

In 2010, the USAID funded a groundwater mitigation project, installing pumps underground to help with water levels around the site and dry out the monuments’ foundations. This means restoration projects like these will have a lasting impact, though this isn’t a problem that’s simply solved.

“We know it's worthwhile to do this because this restoration can have a long-term benefit of stabilizing the monuments,” McClain said. “That doesn't mean we can relax our vigilance because there's just so much damage that has happened. You don't really see an end.” Once the restoration of the Taharka Gate and the Claudius Gate is completed this spring, the OI plans to turn its attention to other monuments in Medinet Habu.