India: Rebuilding woes in the wake of Cyclone Fani

By Soumya Sarkar

India has shown much improvement in saving lives from extreme storms like Cyclone Fani, but enormous challenges remain on the rehabilitation and rebuilding fronts.

Cyclone Fani, which tore through the Bay of Bengal coast in Odisha on May 3 at speeds exceeding 200 km per hour, claimed 41 lives. That’s 41 deaths too many, going by the zero cyclone casualty policy India has been trying to achieve.

Even so, keeping the death toll to low double digits is a huge improvement in a country where severe storms have been known claim live in the tens of thousands. In 1999, when a Super Cyclone hit the same Odisha state in eastern India, over 10,000 people had died.

But cyclones not only kill people. They also cause massive damage to property, and rebuilding from the wreckage sometimes takes years. The October 1999 cyclone, for instance, damaged 1.6 million homes and caused rivers to breach more than 20,000 flood embankments, which together with winds of more 220 km per hour and storm surges as high as 20 feet completely destroyed the winter crop.

It took years for Odisha, one of the poorest states in India, to rebuild and rehabilitate. Even now, 20 years later, there are many instances where families have not yet been rehabilitated and there is property damage from the 1999 storm.

Cyclone Fani, the second severe cyclone to hit Odisha in April-May in 128 years, was no less devastating, rendering more than five million people homeless, besides crippling vital infrastructure.

Increasing frequency

Extreme storms have become more frequent across the world, and scientists hold climate change partly responsible because, among other reasons, sea surface temperatures are rising, favouring conditions that lead to super storms.

There have been devastating storms in recent decades. More than half a million died in the Great Bangladesh Cyclone of 1970. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina killed some 2,000 people in the US and caused damages that have been calculated at more than USD 100 billion.

Technological advancements in early weather warning systems and better disaster response has now been able to keep death tolls in check. India is a stellar case in point. When it became evident in April that a severe storm was forming over the Bay of Bengal, the state disaster management authority swung into action based on early weather warnings.

More that 1.2 million people living in coastal Odisha were evacuated to well-stocked shelters. Thousands of lives that would have been lost were saved.

The path of Cyclone Fani was closely monitored by the India Meteorological Department, which issued frequent advisories. The department’s precise early warnings helped the authorities to conduct a well-targeted evacuation plan, the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction said.

“India’s zero casualty approach to managing extreme weather events is a major contribution to the implementation of the Sendai Framework and the reduction of loss of life from such events,” Mami Mizutori, UN’s Special Representative for Disaster and Risk Reduction, tweeted on May 3, the day Fani made landfall. The Sendai Framework is an international agreement on disaster risk reduction.

Massive loss

But massive destruction could not be averted. The cyclone affected 14 million people, caused extensive damage to more than 16,000 villages and left the cities of Puri and Bhubaneshwar in shambles. The state is still picking up the pieces.

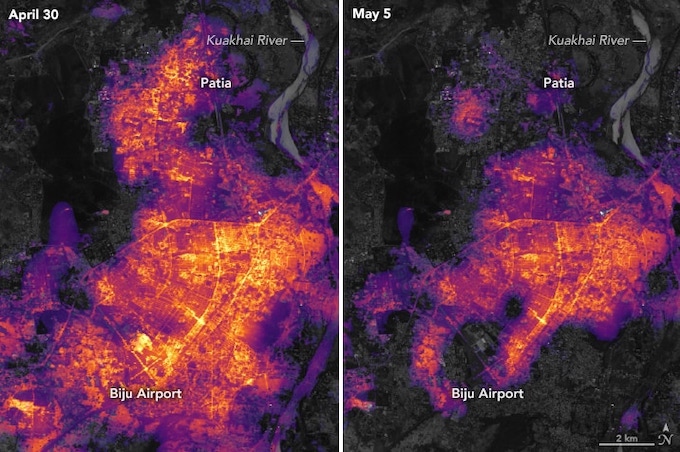

According to data collected by the government and civil society organisations till now, 14 districts have been severely affected. In Puri district, all shanties have been flattened. Bhubaneswar, one of the greenest cities of India, has lost virtually all its green cover. More than 40,000 km of power transmission lines went down. According to early official estimates, as much as 30% of the standing crops have been damaged.

“There is a massive need for immediate relief and long-term restoration and rehabilitation,” said Bismaya Mahapatra, a development professional working in rural areas for many years.

According to eyewitness reports, the post-disaster response in cities hasn’t been good. Electricity and water still remain out of reach in many areas. “In the absence of electricity, the summer heat has made lives even more gruelling. Added to that is water scarcity. Infants, children and older people have been facing acute heat stress,” said Bhubaneswar-based senior journalist Basudev Mahapatra. “The urban poor, who have lost the whole or a part of their makeshift houses in the cyclone, are also deeply vulnerable.”

Repeated rebuilding

This then is the crux of the challenge faced by people affected by severe storms — repeated damage to property, infrastructure and green cover that need to be rebuilt and reinstated every few years. However, between the two major cyclones in 1999 and 2019, not much has been done to replant the trees that were lost earlier.

“Horticulture crops in the state have been destroyed in the affected region and will take years to restore,” Bishnupada Sethi, Special Relief Commissioner with the Odisha government, told Bloomberg news. “About 500,000 people have lost their houses and would need reconstruction.”

Recurring natural disasters exacerbated by climate change present a formidable challenge in an impoverished state like Odisha, according to Saudamini Das, an economist at the Delhi-based Institute of Economic Growth. In fact, she links the economic backwardness of Odisha to disasters as frequent cyclones and droughts limit capital accumulation and investment capacity of the people.

“Frequent disasters force the state to focus on repair, reconstruction and preparedness or on relief and rehabilitation,” she said in a February 2016 study. “It has little scope to engage in developmental activities.” Natural disasters put pressure on the state economy and it’s going to get worse, she said.

Experts say that building climate-resilient structure is the only way to minimise the cost of long-term reconstruction. For instance, some have suggested that the state should move its electricity distribution lines underground.

Fani is a lasting reminder of how climate-resilient infrastructure is needed to reduce long-term costs of redevelopment and restoration, Anumita Roychowdhury, Executive Director of Research and Advocacy at Centre for Science and Environment, wrote in a blog post. “During intense storm surges, vulnerable regions are susceptible to instantaneous damage to infrastructure,” she said. “These regions need quick adoption of design standards to withstand storms, and adapt to high wind speed, heavy rain and flooding to reduce damage.”

As climate change leads to more intense and more frequent storms, floods and droughts, integrating urban and rural planning with disaster management is the only viable way for the future, experts say.