Cascading’ climate risks in the Middle East and North Africa

The next two United Nations climate negotiations will take place in the Middle East and North Africa region (MENA). COP27 will be in Egypt this November, followed by COP28 in the United Arab Emirates next year. Climate change has only recently gained mainstream attention in MENA, where news cycles have tended to be dominated by political security, oil and gas economics, and sectarian tensions.

Extreme weather – including unprecedented heatwaves and flash floods – in MENA countries over the last few years has made the severity of the situation impossible to ignore. Climate projections indicate that such phenomena will intensify. Environmental change will increasingly interact with political and economic dynamics, affecting the region’s people, trading partners and investors. As the Egyptian COP presidency emphasises adaptation needs, it is worth considering what these are in the region and how international cooperation can help mitigate cascading risks.

A uniquely exposed region

The geography of MENA is varied, from occasionally snow-covered pine forests in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco to the lush monsoon-fed climate in Dhofar, south Oman. But as a whole, MENA is the most water-scarce of the world’s major regions. A combination of petroleum rents and foreign aid have over the last half century enabled rapid population growth, urban expansion and increasing food imports. This wealth, together with low levels of accountability, has tended to gloss over environmental fragility. Unsustainable water use, damming for hydropower and unregulated urban build-up has for example brought prosperity to some, yet weakened long-term resilience.

Today, critical levels of resource degradation, overlaid by climate change, are revealing the cracks. Perhaps surprisingly, flooding has emerged as one of the most frequent environmental hazards in the MENA region. Increasing instances of heavy rainfall events in towns and cities ill prepared to deal with flood waters, such as Sana’a in Yemen, Jeddah in Saudi Arabia and Shiraz in Iran, have caused loss of life and significant damage. More such events are expected.

Low-lying and densely populated areas of coastal north Africa and the Gulf are particularly vulnerable to sea-level rises as our planet warms. Even small rises could have a big impact due to the geographic profile of these areas and the potential for storm surges. The Egyptian city of Alexandria is particularly at risk because it is sinking.

Agriculture has suffered from disjointed policies in MENA countries. Benefitting from cheap fuel and unregulated groundwater extraction, the sector is often dominated by agribusinesses deploying unsustainable irrigation and land use practices. The World Bank estimates that around 45% of the total agricultural area in the region is exposed to salinity, soil nutrient depletion and erosion. Drought-related livelihood losses in Iraq and Syria have driven hundreds of thousands of rural families into cities over the last decade, putting additional pressure on municipal services while rendering small farmers vulnerable to extremist recruitment tactics.

Caused by and causing conflict

Armed conflict has ravaged parts of Syria, Iraq, Libya, Yemen and Gaza over the last decade. From the destruction of water facilities, housing and schools to soil, water and air pollution generated by makeshift oil refineries, conflict is negatively affecting the environment, increasing vulnerability to a host of health and climate impacts. This is evident in land contaminated with toxic remnants of war, or purposely deforested as a tactic of war. In Syria for example, such land cannot be used for food growing, thereby worsening food and livelihood security. Climate change adds an extra layer of instability to this potentially vicious cycle.

Access to and affordability of vital services such as water and electricity are politically sensitive in all countries. But in those under authoritarian rule or where elite groups capture resources, failure of these services undermines government legitimacy, often unleashing public anger at other injustices. For example, the October 2019 uprisings in Iraq and Lebanon were aggravated by gross environmental and public safety failings, namely poor drinking water provision in Iraq, an inadequate response to forest fires in Lebanon, and insufficient power in both countries.

In Khuzestan, southwestern Iran, public anger sparked by the collapse of a building killing over 40 people (blamed on the illegal addition of three storeys) was compounded by long-running water shortages caused by damming, water-inefficient and chemically intensive farming practices, rising food prices, and harsh dust storms in May 2022. As with its neighbouring province of Basra, Iraq, which saw violent clashes with the government following mass water poisonings in 2018, Khuzestan is oil rich. Public frustrations in both provinces are linked to perceptions of inequality and unfairness in wealth distribution.

Cascading impacts

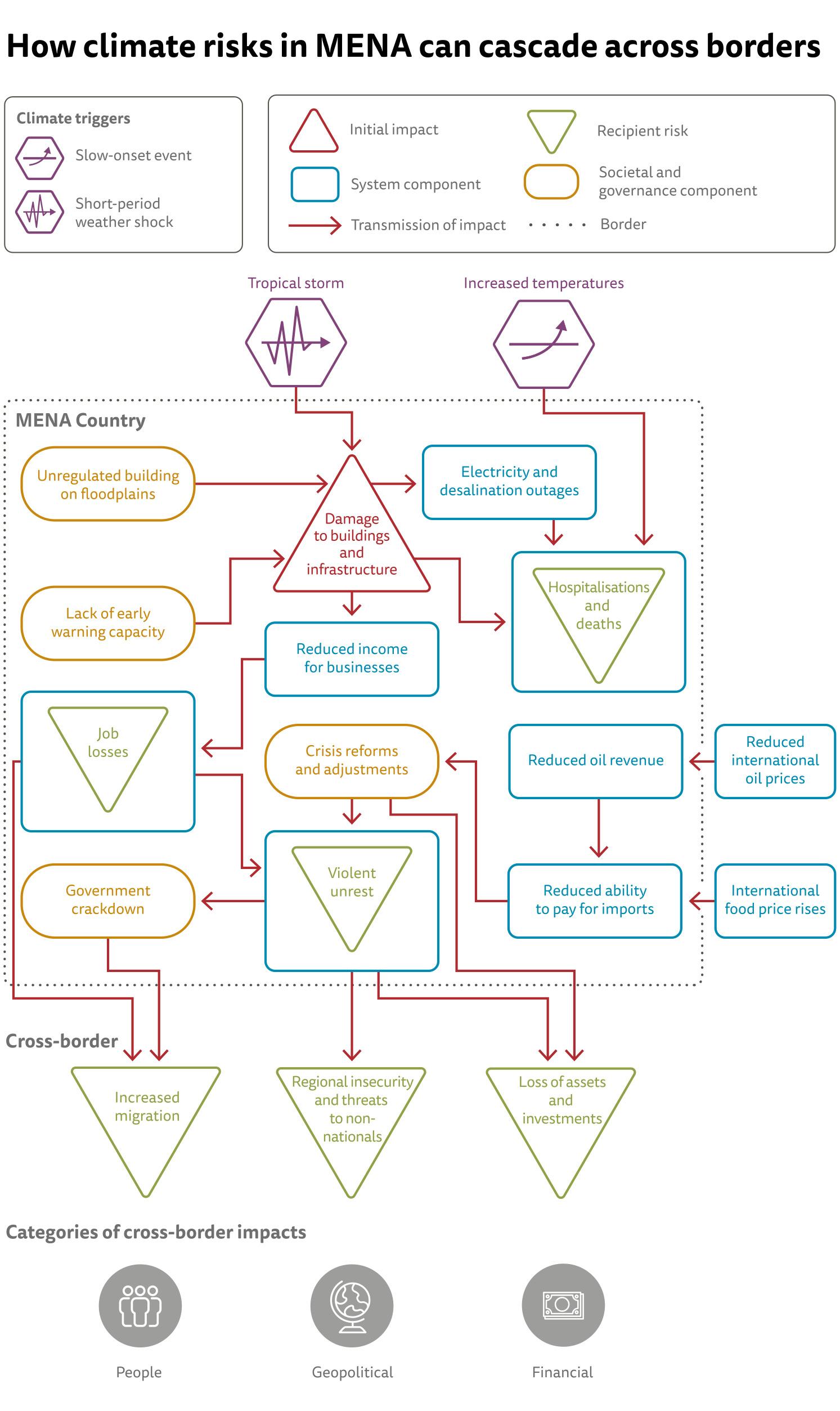

As these examples show, climate change is an additional pressure amidst a complex set of socio-economic and global dynamics. The diagram above illustrates how its effects can compound and cascade depending on the situation on the ground. Primary impacts of climate change – both slow and sudden – are shown in purple at the top. These will have initial impacts on the ground, shaped by the social and economic characteristics of a given region (the red triangle). Further effects will cascade through system components such as infrastructure and economy resulting in electricity and water desalination plant outages and job losses (the blue rectangles). These will potentially have cross-border impacts (green triangles).

Vulnerability to climatic events is not only about physical exposure, but also the ways they will interact with societal and governance components (the yellow lozenges) which also include the prior management of resources, demographic trends and political responses.

Climate impacts will affect food supplies, migration patterns, investments, humanitarian operations and politics in societies far from the original flashpoint As we learned from the experience with Covid-19, and the current war in Ukraine, the effects of a crisis can quickly spread through global systems and networks. In this way, climate impacts will not be limited within national borders or regions, but will cascade, affecting food supplies, migration patterns, investments, humanitarian operations and politics in societies far from the original flashpoint.

Cooperation for resilience at COP27 and 28

As host nation of this year’s COP, Egypt will dedicate special attention to climate-resilient agriculture, sustainable cities, finance for adaptation and equitable transfers for loss and damage. For the UAE, host of COP28 in 2023, climate’s impacts on human security are likely to be high on the agenda. Food and water sustainability as well as energy transition pathways for oil and gas producers should feature strongly through both COPs. This provides ample opportunity for international partners to support resilience in the region.

The context for access to finance and assistance for adaptation is marked on the one hand by strong developing country pressure for faster and larger transfers of climate finance, and on the other, the global infrastructure competition taking off as major powers – the G7 and China – compete for political influence. Both open up resilience opportunities for the MENA region. But an investment rush also risks conflicting objectives that could jeopardise project sustainability for vulnerable societies by widening wealth inequalities, locking in fossil fuel dependence and leaving countries heavily indebted.

To avoid this, climate finance and country development priorities must align. Other forms of finance to the region, such as the billions promised through the Belt and Road Initiative, the Global Gateway and the Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment, must coordinate to enhance socially equitable climate resilience. Learning from experience to date in the region, complementing other climate- and just-transition-related initiatives, and enhancing accountability will reap the highest dividends.

Finally, conversations at the next two COPs will take place against a seismic economic shift driven by a combination of climate and energy security policies and new technology uptake. Together, these stamp a certain, albeit undefined, time limit on fossil fuel profitability. This means that the MENA oil and gas exporting nations, including the six Gulf Cooperation Council countries, as well as Algeria, Iraq, Iran, Libya and the Sudans, have entered a race against time to diversify their economies. Partnerships on resilience to changing environmental realities must therefore also foster green, regenerative economic diversification.