Design charrettes for post-disaster design

The first thoughts after a disaster are never with an interesting design process for the hit area. First concerns need to be with the people that suffer, have to deal with damage or lost relatives. Secondly, the remnants of the disaster should be cleared, so normal life can resume. The grief and sorrow has to find a place in the communities.

In Japan after the 3-11 Tsunami something else happened. Many people left their home ground. It was for many just to dangerous to live close to the nuclear plant, people were simply not alowed to return to their homes or they decided to leave and start again somewhere else.

Apart from repairing and rebuilding, these areas needed to regroup community members. This wasn’t always simple and many governmental programs were condemned because they were just about engineering projects for better protection. Some of the successful projects focused on art, storytelling or healing, ways for the population to gain back some lost ground.

Co-creation of design has proven also to work well under these circumstances. In the Tohuku area two design charrettes have been organised in which residents could redesign their area together with experts.

A design charrete is a beneficial way of harvesting emotions, stories and thoughts around rebuilding the community.

In such a complex context, design can play a relieving role. Design is especially good at visualising and manifesting spatial concepts and ideas people in the area might have. It is capable of making the complexity of problems tangible, so people can identify themselves with the results developed during the charrette.

A design approach delivers:

- A new and positive perspective. Especially after a disaster it is easy not to be able to see a positive future. Design can help to formulate and visualise this positive future.

- Bonding between people. When people undergo a process of up to a week together they share their thoughts and concerns, and start to collaboratively identify new pathways of solving problems

- The regaining of pride and the sense of belonging. Through the design solutions people can start seeing their old or renewed relation to the land they were living before. Instead of being rejected by your harsh environment as result of the disaster, the design charrette helps to gain a sense of belonging to your area.

- The resolution of spatial problems that have emerged after the disaster. Design integrates solutions for many separate problems and has therefore a lot to offer when spatial solutions are implemented in an integrated way.

The Design charrettes of Minamisoma and Kesennuma

The two charrettes that have been held in Minamisoma and Kesennuma in the Tohuku region illustrate the abovementioned role design can play in transcending the disaster.

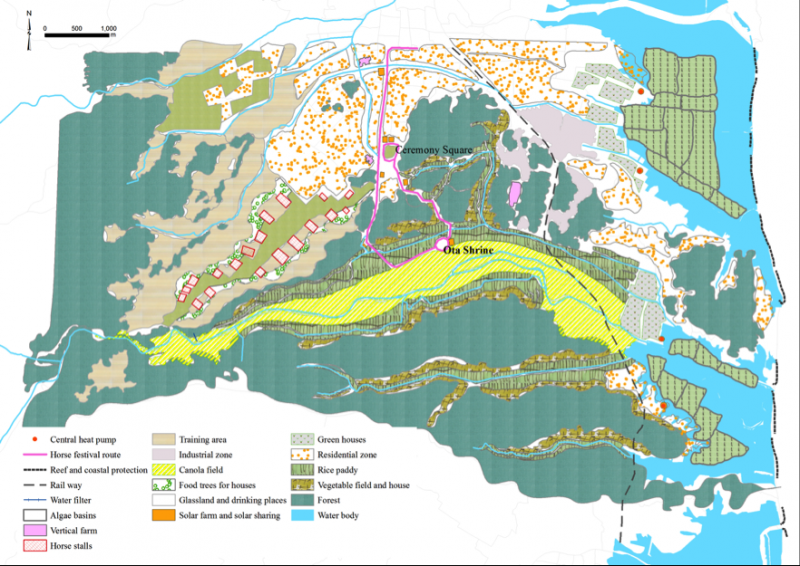

The Minamisoma design charrette combined several ingredients to rethink, reborn and return to the area. The rehabilitation of historic culture, such as repositioning historic shrines and the revitalization of the traditional horserace as a central core for the design, determined not only the spatial base structure but for the people meant also a huge psychological connection to plan and the area. This attention for the historic culture was also reflected in the rehabilitation of traditional professions, such as working with horses and horticulture. Additionally the design process delivered spatial solutions for an alternative coastal protection, which emphasises the adaptive capacity of the coastline, making it more receptive to storm surges. At the same time large algae field were proposed as an extra protection, but also as a source of renewable energy and food. The final design intervention was the reclamation of the agricultural land to make them productive again. Under the radioactive circumstances, the prohibited lands will slowly be released for agricultural production. In a step-by-step process, the local land is firstly used to grow canola, which is independent from radio-activity and still produces biofuels.

Minamisoma design charrette

The design charrette in Kesennuma, remember - reconnect - reform, distinguished traditional storytelling, connecting historic sites, such as shrines, ancient villa’s and cultural sites through a recreational route. This route demarcates the flood-line of the tsunami, to remember where the water reached and to define the boundary where people should and shouldn’t live. In the areas closer to the sea a new memorial site is proposed, and the foundations of devastated houses will be excavated and stewarded by the former residents. The design further comprises of an innovative coastal protection, which creates a flexible coastline and allowing the powers of nature to strengthen the protection, for instance through building up beach and dunes. The coastline will be softened, as land is formed in the sea and sweater may enter the coast. This powerful play of land, sand and water creates an anti-fragile coast, which is much safer than an engineered dam or seawall.

In both charrettes an expert design team worked with residential groups, high school students and governance bodies in a weeklong workshop. During the week, an intensive program was executed with the design team to analyse, design and co-design propositions in an interactive way. This was very successful, because the design charrette helped minimize the Japanese cultural hierarchy, while allowing charrette participants to discuss ideas and concepts with each other without concerns of age, gender or status, which, in Japanese culture, is rare.

The benefits of the design charrette approach in post-disaster contexts are diverse. The experience in the Japanese case study revealed the following:

- It brought people together.

- It gave rise to unconventional ideas.

- It offered a positive perspective on the future.

- The co-design offered cross fertilisation between external experts and local residents.

- People regained pride on their homeland and were more susceptive to return.

- It offered the possibility to give the disaster a place in memory, and to remember.

Professor Rob Roggema is a Landscape Architect and an internationally renowned design-expert on sustainable urbanism, climate adaptation, energy landscapes and urban agriculture. He is Professor of Sustainable Urban Environments in the UTS School of Architecture and has a wealth of industry and academic experience; he has previously held positions at universities in the Netherlands and Australia, State and Municipal governments and design consultancies. Rob developed the Swarm Planning concept, a dynamic way of planning for future adaptation to climate change impacts.

Recent design-concepts Rob has developed include Double Defence, a proposal of a second row of barrier island to protect the coast for storm surges in times of climate change; A Floodable Eemsdelta for a region under threat of flooding, Bushfire Resilient Bendigo, a method of anticipating bushfires by creating a protective shield and slowly moving away the town; and FoodRoofRio, a rooftop garden with an aquaponic system that provides food for the whole family in Cantagalo favela in Rio de Janeiro.

Rob has designed and led over 30 design charrettes around the world, involving communities, academics, governments and industries in the design process. He has written three books on climate adaptation and design, four on Urban Agriculture, and one each about design charrettes, Rio’s FoodRoofs and Design for Recovery in Japan.