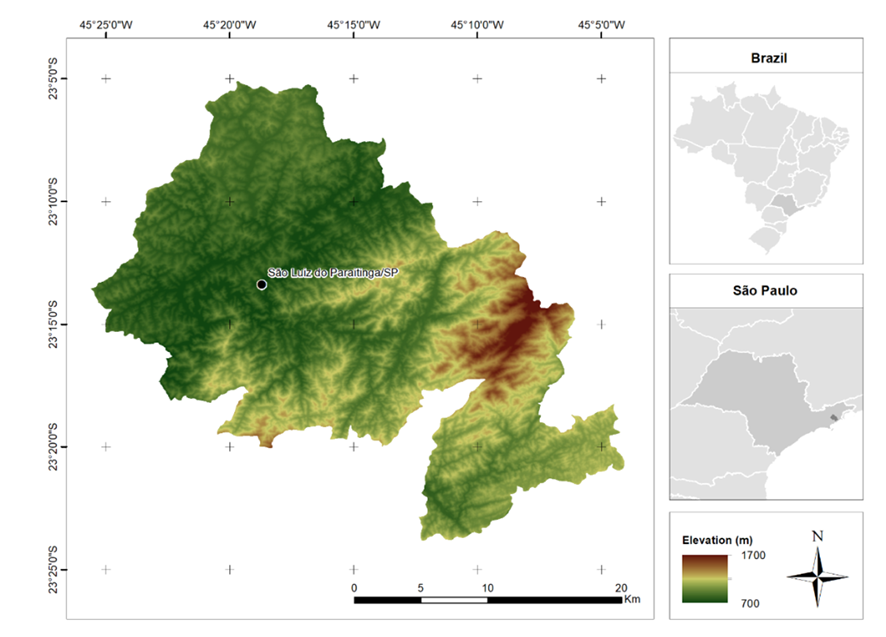

Social innovations to enhance disaster risk reduction in São Luiz do Paraitinga, Brazil

Why social innovations to enhance disaster risk reduction?

Between 2000 and 2018, Brazil was hit by 65 flood-related disasters, representing close to 71% of disasters recorded. They were also the deadliest – causing 2,435 fatalities out of a total of 2,767.

It is therefore necessary to examine how societies respond to hazards using social innovations. Social innovations, according to Geoff Mulgan (2006), include actions that are related to the creation of long-lasting innovative activities, and services that are motivated by a social need.

This project looks at how social innovations could enhance disaster risk reduction (DRR) – and which innovations would be best suited to achieving results – in São Luiz do Paraitinga, Brazil, a city that is frequently exposed to floods and landslides.

What did we do?

We conducted a number of activities to look at which social innovations could enhance DRR in São Luiz do Paraitinga, and how they could be applied. Local high school teachers and civil defense members were enlisted to the core group to organize activities, and other participants (including the general public, high school teachers, and students) contributed by sharing their insights.

A participatory 3D model

The first activities were facilitated by the implementation of a low-cost participatory 3D model (P3DM) –a communicative facilitation method that can be used to stimulate participation in characterizing hazards, vulnerabilities, capacities, and disasters.

The P3DM was used in the town’s main square and the only high school, with different focus groups (general public, high school employees and students) and using a range of methods (semi-structured interviews, roundtable conversations, discussions, and presentations) to understand what social innovations could be led by locals to enhance DRR, and how.

Participatory mapping

The second activity was participatory mapping – a method that requires accessible geographical information, and the participation of specialists to communicate data to high school students.

The participatory mapping activity was facilitated with high school students at a workshop during which the participants were asked to identify hazard-prone areas and social groups with higher vulnerability, and then to propose DRR measures.

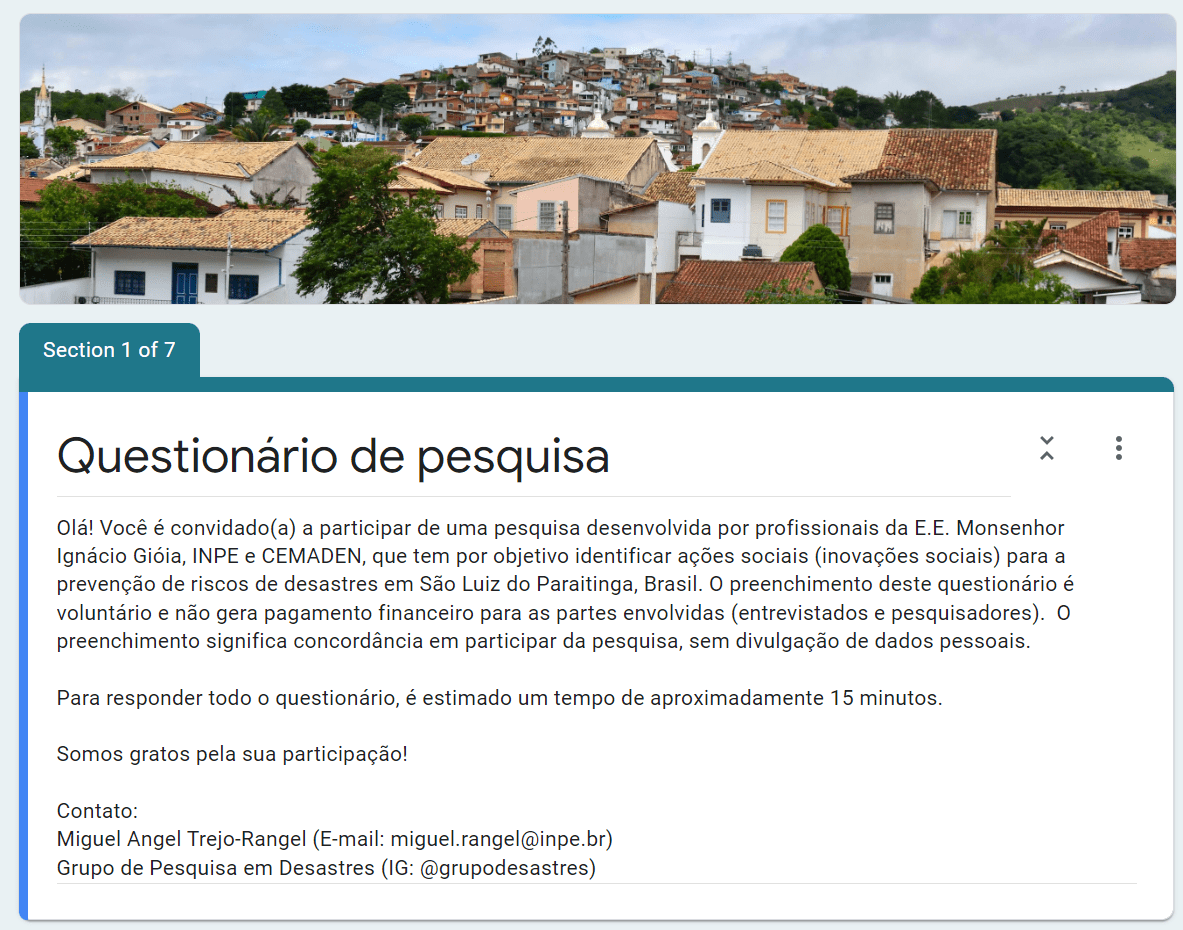

Survey

After collecting the social innovations that could be implemented for the city, we shared a survey of 26 questions. The survey was useful for gathering data about which actions interest responders most, to know what partnerships could be developed and what resources would be needed to implement the actions.

Seminar

Lastly, we organized a two-day hybrid seminar, at which both in-person and online participants engaged in roundtable conversations, a music presentation, a photography exhibition, and pedagogical games, as well as presenting the main outcomes of previous activities.

What did we find?

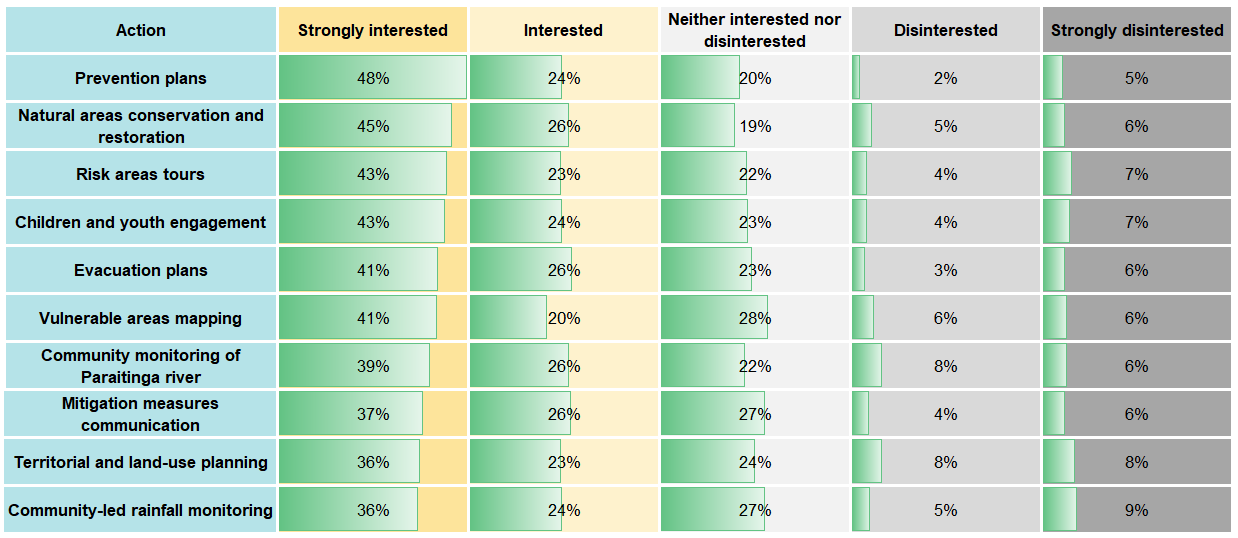

The project gave high school employees, students, and the general public an opportunity to identify social innovations to enhance DRR in their city. The ten actions selected by vote were:

- prevention plans

- natural area conservation and restoration

- tours of at-risk areas

- engagement of children and youth

- evacuation plans

- mapping of vulnerable areas

- community monitoring of the Paraitinga river

- communication mitigation measures

- territorial and land-use planning

- community-led rainfall monitoring.

These measures should be implemented by the community, with support from the relevant critical sectors (such as government, NGOs, and the private sector). The plan also requires technical, financial, and human resources, as well as incentives to motivate community members during the implementation processes.

Finally, the project noted that public policies should support the implementation of social innovations to promote disaster risk reduction, but these policies should also be developed using a social-innovation approach.

What happens next?

As a group, we recognize that DRR is a continuous process that should include a wide range of stakeholders. We therefore encourage other DRR facilitators and locals to see this project as a replicable practice that can be adapted to other contexts, in other areas exposed to the impact of other hazards. But most importantly, it is an intervention that includes the groups directly impacted by disasters.

As we move forward, we need to make sure that the proposals are implemented and supported by the stakeholders who can provide resources and incentives to make these actions possible.

Miguel Angel Trejo-Rangel is a doctor in Earth System Science by the National Institute for Space Research, researcher at the Disaster Research Group (GPD) and specialist in Disaster Risk Reduction.

Victor Marchezini is a Sociologist of Disasters, researcher at the National Early Warning and Monitoring Centre of Natural Disasters in Brazil, professor of the Earth System Science postgraduate program at the National Institute for Space Research, and coordinator of the Disaster Research Group (GPD).

Daniel Messias dos Santos is a historian and pedagogue with a master’s degree in human development, and is currently a high school teacher at the State School Monshenhor Ignácio Gióia in São Luiz do Paraitinga.

Marina Gabos Medeiros is a historian, and is currently a high school teacher at the State School Monshenhor Ignácio Gióia in São Luiz do Paraitinga.

José Carlos Luiz Rodrigues is the head of the Civil Defense in São Luiz do Paraitinga, São Paulo, Brazil.

Editors' recommendations

- Climate risk country profile: Brazil

- Extreme weather and climate events in Brazil

- Improving climate resilience of federal road network in Brazil

- "Brazil on drought alert, faces worst dry spell in 91 years

- As Amazon destruction continues, Brazil faces future of floods, drought

- 2020: The escalation of extreme rainfall events in Brazil