A wake-up call for water supply: Updating out-of-date approaches for future development, social and pandemic relevance

By Jamie Bartram and Guy Howard

- Sufficient drinking water underpins health, wellbeing and prosperity, through hydration, hygiene and productive uses.

- Evidence for how much water is needed and where it should be accessible is consolidated and synthesised in a new World Health Organization publication.

- We need a realignment of policy programming and practice to reflect health and human right needs, so that reliable continuous running water is available in every home; in every school and workplace, market and travel hub, orphanage and prison; and for every displaced person.

For decades, the tangible human need for water – for survival, health and prosperity – has been reflected in a series of UN development decades, (including one dedicated just to water and sanitation). While the International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade (the 1980s) was widely condemned as lacklustre, progress under the Millennium Development Goals (1990–2015) greatly exceeded the target to halve the proportion of those without ‘access’ to drinking water.

Remarkably, throughout those initiatives, evidence for the quantities of water and the levels of ‘service’ required to meet their over-arching goals of reducing poverty and improving health was missing. So, well into the 21st century, these initiatives still sought to ensure a shared community source of water, like a village handpump or a standpost in an informal settlement.

This was largely justified, to ensure ‘some for all’ rather than ‘all for some’. However, such targets had little justification in public health terms and consigned billions of people to invest precious time and energy in the physical collection of water. That this is inadequate for health needs and to satisfy human rights is self-evident because too little water is collected for hygiene, especially among those living far from water sources and those living with physical or mental disabilities. The act of water collection and carriage is itself hazardous for the collector, and water is frequently contaminated during collection, transport and household storage. Guidelines for the amount of water that should be available were also inconsistent – the figure of 20 litres (a bucketful) of water per person per day is common but chasing its origins is practically impossible and these guidelines seem more driven by what people can physically collect from shared water sources outside their home than public health sufficiency.

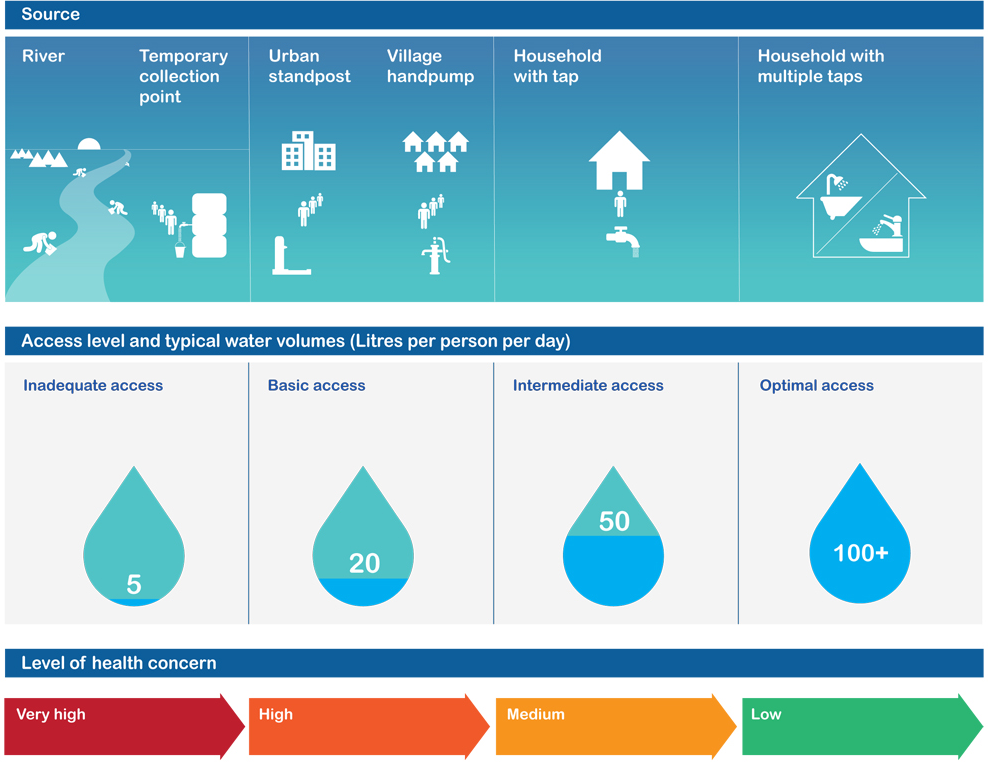

The sparse and disparate evidence about water needs was first consolidated in 2003, under an initiative by the World Health Organization, as Domestic Water Quantity Service Level and Health. A just-released second edition of that influential publication and associated infographic confirms the inadequacy of international ambition for water supply in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), for the challenges of protecting health, fostering wellbeing, and preparedness for and response to disease pandemics.

Hydration reflects the most fundamental human need, for which individual requirements vary substantially. They are greater in hot and humid environments, where combined with physical labour a lactating woman may require as much as 5.3 L/ day – even more under extreme conditions. Typical requirements are considerably less, 2–3 litres per person per day in temperate climates. The amounts of water necessary for other needs are under-studied and evidence is sparse. Experience suggests around 20 litres per person can satisfy requirements for hydration, cooking, food hygiene, and hand- and face-washing under most circumstances, but this amount should not be interpreted as sufficient or ideal. Other uses of water: for bathing, laundry and household cleaning, and for productive uses (like kitchen gardening and for small livestock which are prevalent among low-income households), add greatly to this amount.

Domestic Water Quantity Service Level and Health compares these requirements with the realistic water use associated with different water service levels– community source (20lpd), source in yard (50lpd) and water supply within premises (over 100lpd). However, a simplistic focus on measuring amounts of water and checking where people collect water underplays the effects of reliability and continuity that reduce water availability for many; and service level interacts with water safety. Inescapably, living with the 20-litre minimum is challenging, especially in resource constrained households, where for example storage containers may be in short supply – precisely where these levels of supply are most prevalent.

Household water access, adequacy and health (WHO)

We have seen pandemics repeatedly in recent decades – notably SARS, Influenza H1N1 and COVID – as well as the ongoing cholera pandemic, the seventh, which has been ongoing since 1961 and whose remorseless familiarity means it attracts little attention despite its annual toll in low-income countries. The current COVID pandemic amply illustrates the effects that these events have on health, welfare and economy – and the investments that governments and their citizens are willing to make to control and contain them. Preparedness for and response to pandemics makes two demands on domestic water supply: that it minimises inter-household mixing (associated with water collection from community sources); and that it enables and positively encourages hygiene behaviours such as frequent handwashing. This is true for diverse disease-causing agents, extending beyond the coronaviruses that have recently demanded massive international responses, so such investments have wide-reaching relevance and benefits.

Recommendations – such as that for frequent handwashing – that are widespread for public health protection under outbreak, including pandemic, conditions increase water quantities required far above those outlined above. The unavoidable conclusion drawn from the 2nd edition of Domestic Water Quantity Service Level and Health is that safeguards critical in pandemic control are unattainable and unsustainable with less than within-household access to running water. Any lesser service level is unlikely to encourage the behaviours demanded and transfers responsibility from public bodies onto individuals to manage infection risks in a public health crisis, with disproportionate burden to the least served. Within-household running water will confront water professionals with wastewater and drainage challenges alongside those of ensuring reliable supply.

Governments worldwide defined their ambition to achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water by 2030 in the SDGs. But evidence from Domestic Water Quantity Service Level and Health, and lessons from pandemics, confirm that the SDG monitoring benchmark of at least a protected water source-in-yard for every dwelling is misaligned with the needs for health protection, under both ‘normal’ and pandemic circumstances. Worldwide, policies, programming and practice are being realigned away from the ‘community water source’ provision target and away from a ‘some for all’ philosophy, to ensure ‘sufficient for everyone’.

To be commensurate with our globally-shared need to prevent and control disease, to foster health and development for all, and to reflect human rights, we here:

- call for continuous, reliable and running water within every household and healthcare setting;

- call for sufficient water to be available – without cost at point of use – in schools and workplaces; in markets and public transport hubs; and for those vulnerable by setting in orphanages and prisons; and for those displaced as refugees, internally displaced persons, or homeless;

- call on governments to use public funds towards the above calls, whether acting domestically or through international aid.