How the Caribbean is building climate resilience

The Caribbean is already bearing the brunt of climate change. Governments in the region are taking steps to combat it, but are they enough?

Summary

- Small island nations in the Caribbean are among the countries in the world most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, including rising sea levels, coastal erosion, and stronger and more frequent storms.

- Several countries, including Barbados and Dominica, stand out for their ambitious plans to reduce their emissions and invest in more climate-resilient infrastructure.

- But climate finance remains a challenge as Caribbean nations struggle with heavy debt burdens, despite receiving some regional and international support.

Introduction

The Caribbean is one of the regions of the world most vulnerable to climate change. Its large coastal populations and exposed location leave it at the mercy of rising sea levels, stronger storms, and worsening drought. Increasing temperatures, meanwhile, threaten its unique biodiversity. Despite their meager contributions to global greenhouse gas emissions, the Caribbean’s thirteen sovereign nations are already bearing the brunt of these climate disruptions, putting many of these tourism-dependent countries deeply in debt and spurring increased migration across the region.

Scientists say that without immediate action, the Caribbean could eventually become nearly uninhabitable. Countries such as Barbados and Dominica have implemented a range of mitigation and adaptation measures, including increasing public spending on resilient infrastructure, and many have set ambitious targets for emissions reductions. But with the region requiring significantly more help to stave off the worst effects, some leaders in particular are pushing for fundamental reforms of global development aid and climate financing.

How much does climate change threaten the Caribbean?

The United Nations considers the Caribbean to be “ground zero” in the global climate emergency. Classified as small island developing states (SIDS) along with twenty-six other countries, Caribbean nations face particular risks due to their exposed location, relative isolation, and small size. Some of these include:

- more pronounced sea-level rise;

- increased frequency of extreme weather events, such as hurricanes and tropical storms;

- increased rainfall and flooding;

- dangerous high temperatures;

- coastal erosion and saltwater intrusion; and

- longer dry seasons and shorter wet seasons.

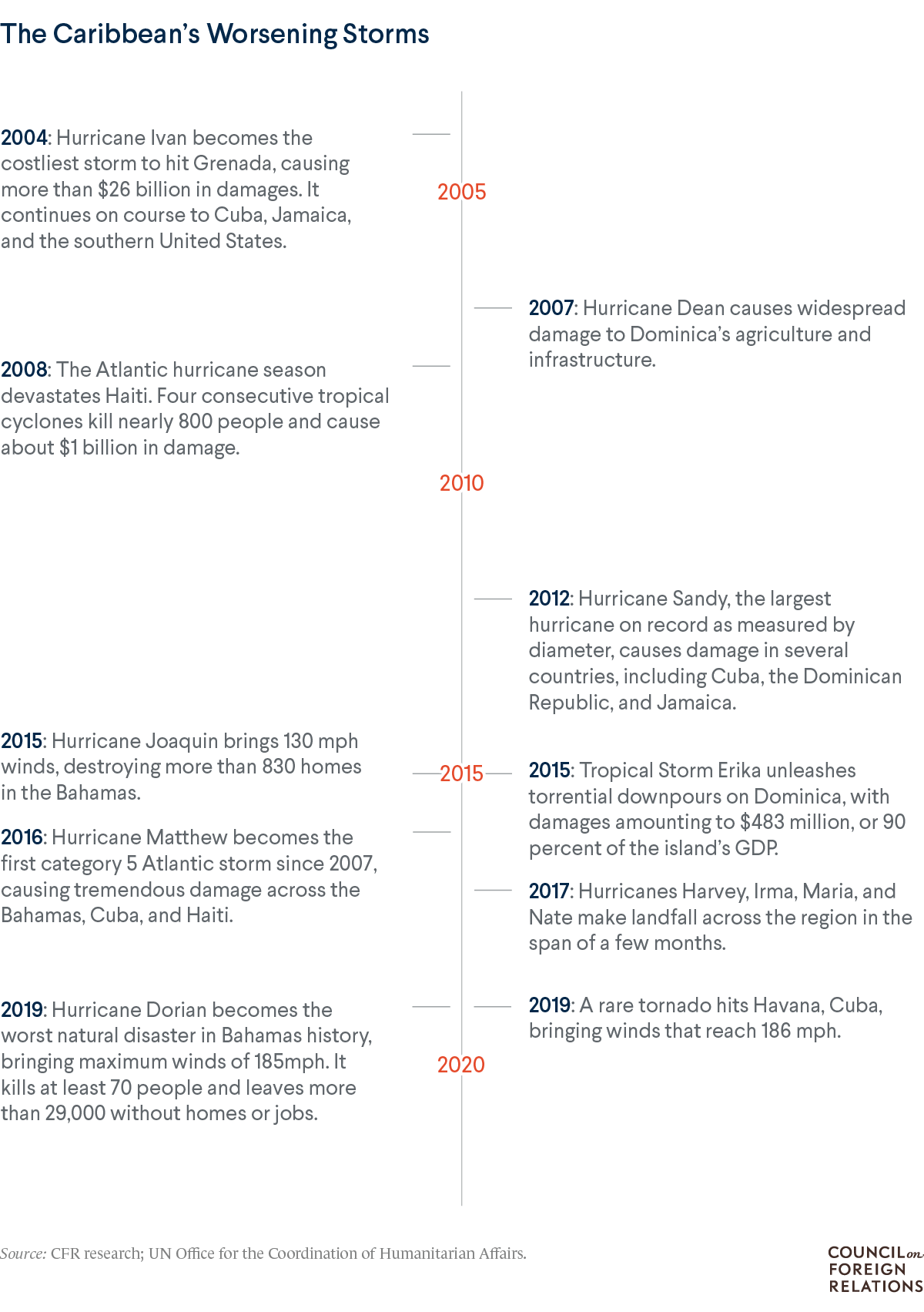

Experts say some Caribbean islands could eventually become uninhabitable. A common feature among SIDS—including those in Oceania and the Indian Ocean—is a high coastline-to-land ratio, meaning that any rise in the sea level is likely to have an outsized impact on the agricultural lands, infrastructure, and populations located along a country’s coast. Some of the most at-risk countries include low-lying islands in the Caribbean Basin, such as the Bahamas and Trinidad and Tobago, whose surfaces are only a few meters above sea level. Several other islands, including Barbados and Dominica, lie inside the so-called “Hurricane Alley” in the Atlantic Ocean. In the nearly two decades between 2000 and 2019, the Bahamas and Haiti ranked among the top ten countries and territories globally that were most affected by extreme weather events [PDF].

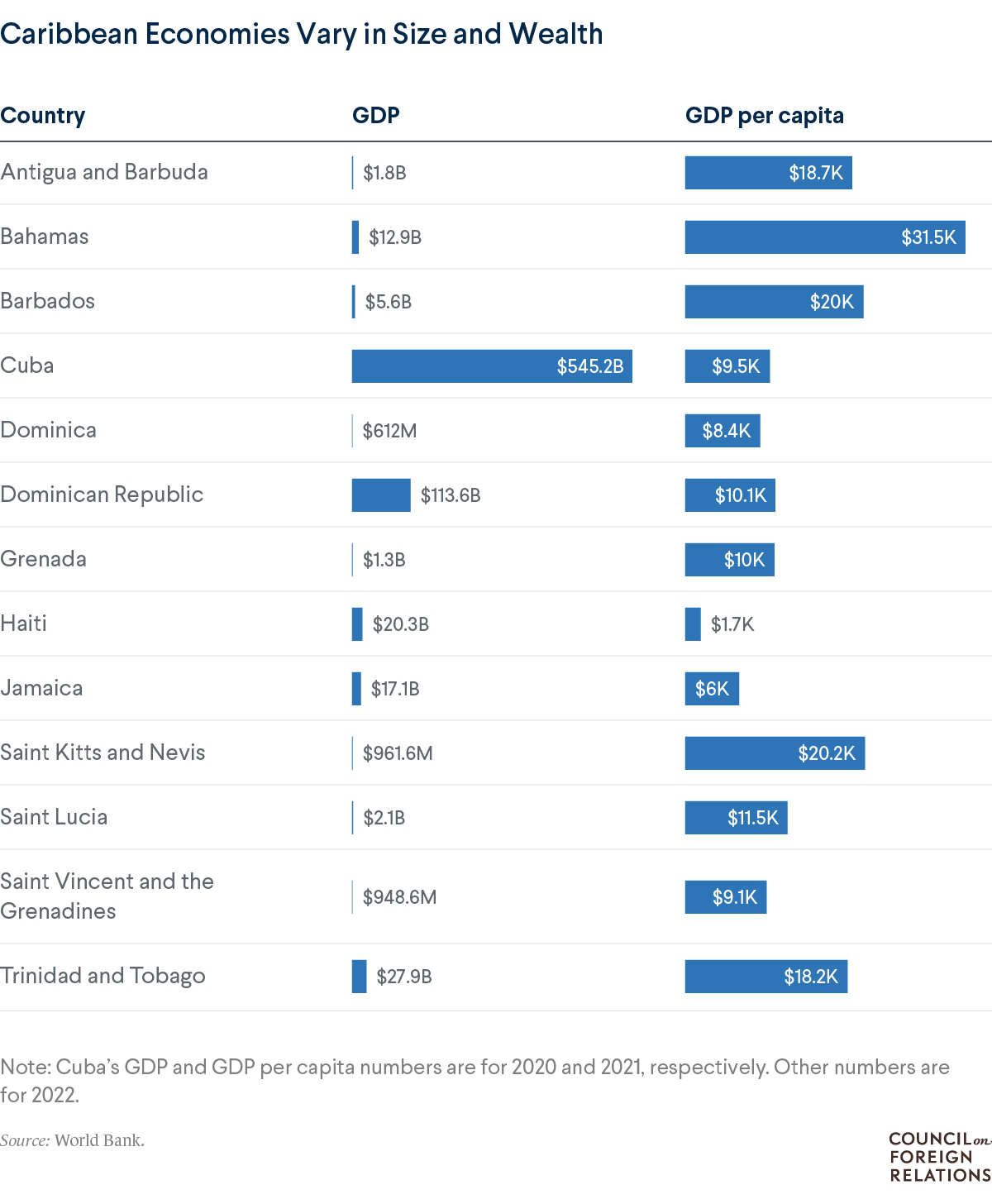

“The Caribbean islands are essentially a microcosm of the challenges we’re all facing,” says Stephen E. Flynn, founding director of Northeastern University’s Global Resilience Institute. Compared to the rest of the world, SIDS face unique financial constraints that increase their vulnerability to climate-induced economic shocks. Their economies are generally smaller and less diversified, characterized by a high dependence on imports, tourism, and remittances, and they often struggle to raise funds for infrastructure development and climate measures. In many cases, they are forced to take on massive debt to recover from natural disasters; Caribbean nations are among the most highly indebted in the world.

According to a 2020 study by Climate Analytics, a Berlin-based nonprofit, climate damages in the Caribbean are projected to increase from 5 percent of regional gross domestic product (GDP) in 2025 to more than 20 percent by 2100 under current trends. (In 2019, Hurricane Dorian alone cost the Bahamas an estimated $3.4 billion—more than a quarter of the country’s GDP.) Other projections put the annual cost of climate disruptions at $22 billion [PDF] by 2050.

What are some of the Caribbean’s most pressing climate concerns?

Climate change can have significant knock-on effects on various industries, ecosystems, and communities.

Agriculture. Any hit to the agricultural industry, which employed 11 percent of the Caribbean’s workforce in 2021, will further challenge a region that relies heavily on food imports due to a scarcity of suitable farmland and limited freshwater. Hotter temperatures, droughts, flooding, and more frequent storms are further reducing water availability, triggering heavier rainfall, eroding soil, damaging crop yields, and harming livestock. Growing food insecurity is a concern as natural disasters can contaminate food and water supplies and increase the spread of food-, water-, and vector-borne illnesses such as cholera and malaria. Altering sea temperatures and currents also threaten the fishing industry, an important driver of food security and economic growth in the region.

Infrastructure. Rising sea levels, more frequent earthquakes, and extreme storms threaten energy and transportation hubs, homes, health-care facilities, and schools. The massive earthquake that struck Haiti in 2010, for example, damaged or destroyed more than three hundred thousand homes [PDF], while the island lost some 60 percent of its administrative and economic infrastructure. Major natural disasters can also threaten global energy markets by disrupting or damaging oil platforms, gas pipelines, and electrical grids, hindering recovery efforts [PDF]. Energy prices in the Caribbean are already among the highest in the world, with several countries depending on imported oil to meet approximately 90 percent of their energy needs. Poor urban planning, substandard housing, and large coastal populations can magnify the impact of these disasters.

Tourism. The Caribbean is the most tourism-dependent region in the world. In 2021, the travel and tourism sector contributed more than $39 billion to the region’s GDP. However, analysts say that climate effects such as reduced rainfall, prolonged heat waves, and the loss or deterioration of natural attractions are already impacting the Caribbean’s tourism industry. A 2022 study found that sea-level rise alone could result in a 38 to 47 percent reduction in tourism revenue by 2100.

Biodiversity. Climate change puts the Caribbean’s unique biodiversity, including more than a thousand species of fish and marine mammals and over eleven thousand plant species—most of which are endemic—at risk of habitat loss and extinction. The region is home to 10 percent of the world’s coral reefs, which are already undergoing bleaching—this is when their ecosystems are weakened by increasing water temperatures.

Migration. Most climate-induced migration occurs within a country’s borders; between 2008 and 2022, close to ten million people in the region were internally displaced by natural disasters, with the number projected to rise. Cross-border migration is also likely to increase, posing thorny legal and logistical issues as people fleeing climate extremes are not currently recognized under international law. In 2020, the Caribbean had one of the highest emigration rates in the world, with the number of migrants leaving the region more than doubling since 1990. Most head for the United States, as well as Europe and South America.

What are notable examples of governments taking action?

The region’s governments have recognized climate change as one of their top concerns. Many have committed to ambitious timetables to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions as part of the 2015 Paris Agreement; others are seeking to generate more power from renewable energy and limit their use of fossil fuels, among other measures.

Under Prime Minister Mia Mottley, Barbados has developed a plan to phase out fossil fuels entirely by 2030 and created a national strategy to boost climate resilience, known as Roofs to Reefs. The program will direct public investment toward reinforcing home construction; increasing sustainable land use; improving freshwater storage capacity; and restoring coral reefs, which help protect coastlines from waves, storms, and floods. Mottley is spearheading an initiative focused on reforming the global financial system [PDF]. It calls on global development banks, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), to mobilize an additional $1 trillion of lending to lower-income countries for climate resilience measures, as well as debt payment suspensions during natural disasters. She has also pressed the IMF to allow more “fiscal space” to these countries by providing more grants rather than loans.

In 2020, Jamaica became the first Caribbean country to submit an updated climate action plan that sets more ambitious targets for reducing emissions in both the energy and land-use sectors. Kingston is implementing projects to boost energy efficiency and water conservation, including by using improved irrigation systems provided as part of a UN-backed program to address water insecurity amid worsening drought conditions. Other UN programs have sought to restore watersheds and rehabilitate wetlands to mitigate damage caused by flooding and droughts. Jamaica is also one of several countries in the region that are taking steps to diversify their tourism markets [PDF], including by upgrading cruise ports and facilities; developing local cultural and heritage sites; and encouraging agritourism and ecotourism, more environmentally-friendly alternatives.

Meanwhile, Dominica has created a new agency to position it as a world leader in climate-resilience efforts by the end of the decade. In 2018, the government established the Climate Resilience Execution Agency for Dominica with the aim of developing adaptive infrastructure, accelerating economic growth, and bolstering the island’s ability to respond to climate events. Already, officials have established a community-based early warning system and built more climate-resilient infrastructure, including shelters, roads and bridges, and seawalls. Dominica has also prioritized acquiring global investment to develop and strengthen national infrastructure; for the past six years, it has been ranked by CBI Index as having the top citizenship by investment (CBI) program.

What is being done at the regional level?

Coordinating the region’s response is the Belize-based Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre (CCCCC). Created in 2002, it collects and stores regional climate information and data and offers policy advice to members of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), a regional economic and political bloc. The CCCCC is recognized by the UN Environment Program and other international agencies as the focal point for tackling climate change in the Caribbean.

There are also several regional initiatives, such as the Climate Governance Initiative for the Caribbean project (2021–2024), which provides member countries with legal and political guidance on reaching their Paris climate commitments and seeks to amplify Caribbean voices in international climate talks. Previous plans have included the Caribbean Initiative Strategy [PDF] (2009–2012), which sought to increase information-sharing among island nations and pushed for a greater focus on ecological conservation, among other priorities.

Climate finance is another major challenge for Caribbean nations. As middle or high-income countries, they generally do not qualify for low-interest loans or other forms of aid from multilateral institutions like the IMF and the World Bank, leaving them with heavy debt burdens after a disaster strikes. The World Bank’s Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility, a regional disaster insurance fund capitalized by Western countries and international organizations, has made more than fifty payouts totaling over $245 million since its inception in 2007. But critics say the fund’s insurance premiums are too high and it lacks the money to address the region’s needs, with some proposing to expand the fund’s membership to include other small states around the world in an effort to reduce costs. Countries can also restructure some of their debt through the Caribbean Resilience Fund or, in some cases, get portions of their debt forgiven in exchange for investing in local environmental conservation measures. There is also the option to finance disaster risk management using loans and grants issued by the Caribbean Development Bank [PDF].

What international support have Caribbean countries received?

At the international level, Caribbean nations are part of the Alliance of Small Island States, an informal grouping that advocates for its interests in global fora. The bloc was one of the major advocates for the landmark 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the first global treaty to address the issue. At the UN climate summit in 2022, SIDS were instrumental in pushing for the creation of the nascent Loss and Damage Fund to provide financial assistance to the most at-risk developing nations. The United Nations also has a host of programs that aim to address climate change in the region, including those that help countries formulate national adaptation plans and expand their knowledge of renewable energy options, such as using solar power.

The region also receives international aid from several additional sources. Since 1994, the European Union has invested nearly $380 million in Latin America and the Caribbean through its disaster preparedness program, reaching some thirty million people.

Likewise, the United States has taken steps to support climate adaptation measures in the region. In June 2022, the Joe Biden administration established the U.S.-Caribbean Partnership to Address the Climate Crisis 2030 (PACC 2030), which aims to mobilize billions of dollars for projects focused on strengthening energy security, critical infrastructure, and local economies in the Caribbean. More recently, the administration allocated more than $100 million in new funding, including $98 million from the U.S. Agency for International Development, to Caribbean nations to address climate, energy, food, security, and humanitarian needs. John Kerry, the U.S. climate envoy, has pointed to the need for trillions of dollars in international financing for Caribbean island nations, but efforts to mobilize funds have fallen short as international banks are increasingly leaving the region.

“Our countries in the Caribbean, we play lotto, or roulette, as to which one will be hit,” said Mottley in 2022. “But I would have thought, given the exposure of the [U.S.] southeastern and eastern seaboard, there would be a greater compelling framework for us to treat these issues.”

Recommended Resources

This report [PDF] by Global Americans explains how vulnerable the Caribbean is in the face of climate change and offers actionable policy recommendations.

This 2022 report by the World Meteorological Organization looks at the status of critical climate indicators across Latin America and the Caribbean.

BBC’s Jose Alison Kentish details how the island of Dominica has ambitious plans to become the world’s first climate-resilient country by 2030.

CFR’s World101 library dives into everything to know about climate change.

This Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland unpacks the successes and failures of major global climate agreements.