10 ways to tackle climate displacement in the run up to 2030

By Barbara Essig and Bina Desai

Here is our list of 10 opportunities to help overcome common challenges for dealing with disaster and climate displacement over the next 10 years. As we enter a new decade, it is time to realise the urgency of the issue and use this opportunity as a catalyst for new and innovative solutions.

Displacement associated with disasters and the effects of climate change is one of today’s major humanitarian and development challenges. In the first half of 2020 alone, disasters triggered 9.8 million new displacements, and most were linked to weather-related hazards such as storms, floods and droughts. Climate change can increase the intensity and affect the frequency and seasonal patterns of these hazards.

Invest in innovative data collection and monitoring

Data is the prism through which we perceive displacement and it helps us to focus our actions. It tells us who has been displaced where, for how long, and what the triggering events are. Yet, data is difficult to obtain in certain contexts or else limited to the numbers without additional information on age, gender, specific vulnerabilities or long-term trends. Innovative data monitoring can help us close some of these gaps. In cooperation with Facebook, IDMC used aggregated and anonymised location data to obtain information about displacement patterns after Cyclone Fani in India and Bangladesh, and Typhoon Hagibis in Japan. Satellite images allow for a rapid impact assessment in the immediate aftermath of a disaster, and participatory tools such as community mapping allow for a better understanding of small-scale, local events in difficult-to-access areas.

Learn how to tackle slow-onset events

Drought, sea-level rise, and glacial retreat are all directly linked to the negative effects of climate change. The impact of these so-called slow-onset events on populations and the environment is most likely to increase in the coming years as climate change progresses. Since the effect of slow-onset events is a gradual one, the resulting displacement is difficult to grasp as the example of Somalia shows. In 2018, 249,000 displacements in the country were associated with drought. Drought was, however, only one of many drivers as lack of livelihoods, general poverty and conflict were also pushing people away. Developing a better understanding of these interlinked drivers will be crucial in finding appropriate prevention and mitigation measures before the point of no return is reached.

Keep an eye on small scale events

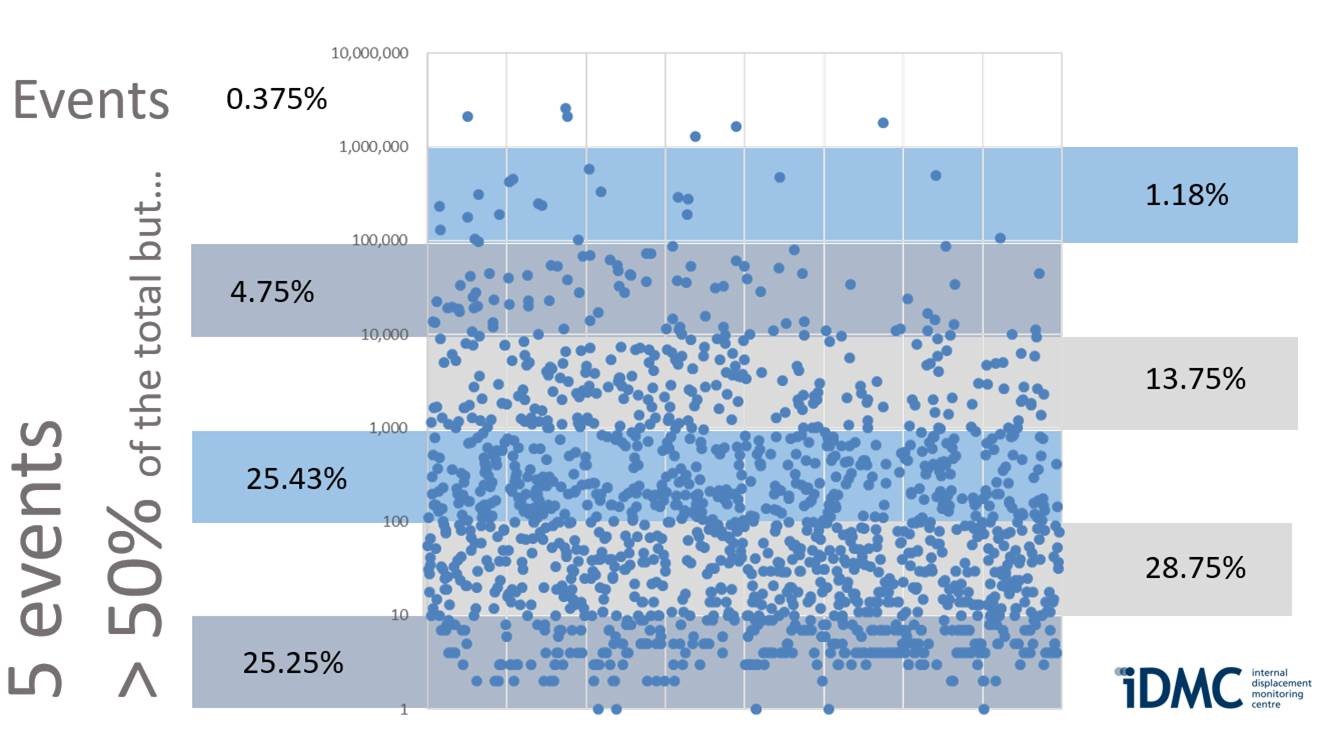

When it comes to disaster displacement, it is usually monstrous tropical storms, devastating earthquakes or torrential rains and floods that get all our attention. A significant proportion of disaster displacement is, however, triggered by localised, small-scale events that pass under the radar of the general public and the media. An analysis of IDMC’s disaster displacement database shows that 54% of all events in 2019 displaced fewer than 100 people. These events are not part of other, widely-used data repositories such as the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT), which only contains events displacing more than 100 people. This lack of visibility not only leads to less support for the affected population but also less attention directed at efforts to prevent future small-scale disasters.

Realise the potential of forecast models

Since “most disasters that could happen have not happened yet”, knowing when and where disasters are likely to strike and how many people might be impacted is essential. Risk assessment and forecast models can go a long way in helping us prepare for, but also prevent, future displacement. A model developed by IDMC and partners shows, for example, that the risk of displacement due to floods is expected to at least double until 2090, with low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa, south and south-east Asia, Oceania and Latin America disproportionately affected. Based on the localised results of such models, governments can decide where infrastructure needs to be reinforced or in which areas settlements should no longer be allowed. Risk modelling also helps plan the capacity of evacuation centres and assistance needed to support displaced people. Finally, forecast models can provide much-needed evidence in countering the myth of mass, cross-border migration fuelled by climate change.

Fight sensational predictions with data and evidence

When the issue of climate displacement is discussed publicly it is often in the form of “climate refugees”, threatening to overrun entire (European) countries. This claim is, however, not backed up by scientific research. On the contrary, data and evidence show that most displacement is internal, with very few people crossing state borders. Still, recent and highly mediatised reports predicted incredibly high numbers of “climate refugees” to be expected in the upcoming decades using questionable approaches. Making sure sound methodologies are used, giving preference to conservative over alarmist estimates and communicating results in a nuanced way is essential to refocus the debate. Only this way can issues key to preventing displacement – such as risk reduction, links with conflict and violence, community engagement and political will – get the (public) attention they deserve.

Focus on risk reduction

More often than not, disasters are still perceived as “natural”; as something that can be prepared for but not prevented. Preventing storms, torrential rains or earthquakes from happening is, of course, difficult. However, preventing and mitigating their impact does not have to be. Regulating how land is used, limiting the degradation of environmental resources or providing social protection to those dependent on natural resources are only a few possible approaches to reducing the exposure and vulnerability of people. Planned relocation, if done in an inclusive and transparent manner, is another. For example, the mountain community of Ghulkin in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan decided to relocate in its entirety in the face of a high risk of flooding from glacial lake outbursts. Through a consultative process, a new site for the village was found, roads were constructed and local social service provision set up, all based on hazard mapping and careful land-use planning.

Recognise links between conflict and climate change

At first sight, there doesn’t seem to be much linking climate change and disasters to conflict and violence. Both can, however, be tightly interwoven and mutually reinforcing. Scarcity of natural resources as a result of slow-onset events such as drought may lead to or aggravate already existing tensions, eventually resulting in conflict. On the other hand, violence may increase risk exposure and vulnerability by destroying farmland and infrastructure or by driving away the population needed to cultivate land. Sometimes, disasters and conflict also simply concur, triggering new displacement of already uprooted populations. This was the case in Yemen in 2020 where heavy rains between March and August led to floods, displacing tens of thousands IDPs who had already fled the country’s conflict. Recognising these links and finding ways how to effectively address them will go a long way in limiting displacement.

Put communities at the centre of the action

No matter if it is for humanitarian aid for displaced populations, for prevention or for preparedness efforts, the first reflex is still often to turn to (inter)national experts for advice. While expert counsel is, of course, valuable, actively integrating local knowledge is equally important. Not only does community engagement help to ensure that what has worked elsewhere will be properly adapted to the local context, collectively designed and adopted measures will also be more easily acceptable for everyone. This is illustrated by the community mapping project Ramani Huria in the Tanzanian city Dar es Salaam. Local volunteers helped to produce detailed maps of the city’s most flood prone areas that today serve as guidance on where to construct housing and public buildings and where not to. By being actively involved in the process, the local community became more aware of existing risk and how to best reduce their exposure.

Join forces to mobilise political will

Wanting something to change is the first step to changing it. None of the above-mentioned issues can be addressed if there is no political will to do so. Since disaster and climate displacement is mostly happening within countries’ own borders, the responsibility to tackle it lies first and foremost with national governments. The international community, civil society, and academia can, however, help relay the urgency of the issue. This can be done by sharing stories of those affected, conducting research on drivers and (economic) impacts of displacement and not least by sharing possible solutions. The GP20 Compilation of National Practices is an important step in this direction. In the upcoming months, IDMC will build on the work done by GP20 and create a global repository of solutions to showcase the best ideas from national governments on how to address and end internal displacement.

Embrace uncertainty and adapt to new challenges

When it comes to climate and disaster displacement there are still many things we don’t know. The consistently high number of displacements in past years shows the systematic nature of associated risks. Luckily, there are a few strategies we know will work in reducing these risks and bringing about development gains for affected populations. Many of them, such as limiting exposure and vulnerability, making use of forecast models or engaging local communities, have been mentioned above. However, we will need to remain flexible in adapting to an ever-changing climate and political, social, and economic environment. The answers we give will need to embrace this uncertainty, seeing it as a challenge and opportunity alike.