How can we enhance inclusivity in warnings? The 5 elements

“Unity, not uniformity, must be our aim. We attain unity only through variety. Differences must be integrated, not annihilated, not absorbed”.

Inclusive warnings can only be achieved through an ongoing, continuous process. While we have seen many high-level commitments and policies supporting the development and implementation of inclusive warnings, there is still considerable effort needed to translate these commitments into effective actions. “Early warnings for all” will not be achieved and maintained through a simple algorithm: it is a complex problem, continuously evolving.

To make warnings truly inclusive we need to involve everyone and design warnings that cover and respond to the full range of human characteristics. These include sex, gender, sexuality, age, race, ethnicity, caste, disabilities (e.g., physical, mental, and cognitive), religion, languages, communication forms, and precarity (e.g., detained, undocumented, homeless, asylum status). However, as inclusivity works beyond any single characteristic, consideration must be given to those with multiple cross-cutting characteristics, classed as ‘intersectional’.

A recent report by the UCL Warning Research Centre on ‘Designing Inclusive and Accessible Warning Systems: Good Practices and Entry Points’ funded by GFDRR World Bank, explores how to find entry points to enhance inclusivity. Taking the four elements of an early warning system the report explores a number of entry points and actions using case studies from the World Bank’s global portfolio of early warning system investments.

1. Disaster risk knowledge: Integration from the first mile

If civil society groups, local leaders, and community-based organizations are included in the development of warnings at the start of the process, they can enhance ‘Disaster Risk Knowledge’ using participatory approaches as an entry point to make it relevant, more inclusive, and more likely to be accepted by society. This was explored in the Developing Risk Awareness through Joint Action (DARAJA) project focused on warnings for extreme weather, targeting urban users in rapidly growing informal settlements and prioritizing the most vulnerable populations (e.g., women, elderly, persons with disabilities), across Kenya and Tanzania. Understanding where these groups and individuals are and ensuring their involvement from the beginning of the EWS design stage is important for establishing multiway communication channels and factoring in feedback loops as early as possible.

Community actions such as cleaning-up drains before the rains have demonstrated how warnings and early action are connected. Consequently, people now listen to, and trust, forecast information. The initiative serves as an example to show the value of including vulnerable populations to create and maintain operational partnerships in the co-design of the products, dissemination channels, and feedback loops for weather forecasts and extreme weather alerts.

2. Observations, monitoring, analysis and forecasting: Building capacity development and outreach

A key entry point is buy-in from local communities, to foster diversity in processes, collaboration, and commitments. Fijian women, for example, set up the Fiji Women’s Weather Watch following two major events (flooding in North Fiji in 2004, and Cyclone Mick in 2009), after it became clear that local women had been excluded from both relief efforts and the design, planning and implementation of ensuing disaster reduction initiatives. The exclusion of women from community awareness negotiating tables often results in a failure to address their needs and gender-sensitive approaches.

Fijian women led this initiative to monitor the weather and provide warnings of hazards. They set up channels to exchange information with the Fiji Meteorological Service, and interpreted messages to make them accessible to the community. To do this they arranged training to develop their communication and engagement skills, so that they could translate technical information into useful and actionable messages in local languages. Initially, this was done via SMS messages sent to a core group of rural women leaders across Fiji. Today the Women’s Weather Watch has evolved into an interoperable intercommunication platform providing weather information and preparedness information, documenting real lived experiences through disasters and climate change, and working closely with the Fiji Met Office and the National Disaster Management Office, providing input of how women’s rights should be integrated to all stages of disasters.

3. Warning dissemination and communication: Expanding inclusivity by raising awareness

The "Let us be more and more prepared" video

Haiti is highly vulnerable to natural hazards and with high poverty levels, vulnerable infrastructure, unplanned urban expansion, and institutional fragility Haiti faces the challenges presented by more hydro-meteorological hazards, driven by global warming. A key entry point by the World Bank was to develop communication, redundancy adaptability, and creativity to enhance waning dissemination. By investing in strengthening disaster and climate resilience to reduce loss of life and economic impact, the project worked with local communities, volunteers from the community who are part of the Municipal Civil Protection Committees, and government agencies to foster engagement to enhance DRR activities, including early warning systems.

By engaging local leaders, integrating local cultures and language, a public warning dissemination and communication programme to strengthen Haiti’s resilience was developed, including a video titled An n prepare n pi plis toujou ! [Let us be more and more prepared]’. The Haitian Civil Protection General Directorate (DGPC) launched this video during a public communication campaign during the hurricane season to present the information in a relatable, and timely manner. Jerry Chandler, Director of DGPC states that “the activity is making a big difference. It’s really giving us a boost in terms of communication to the public. What's important is to find ways to engage the public.”

Engagement is a central part of inclusivity.

4. Preparedness and response capacity: Building a local and national system

Understanding individual and collective risk and how to respond to it with alert messaging is key to maintaining the ability to respond safely and appropriately to warnings. However, closing the gap between government and communities to achieve this goal can be challenging. An excellent example is the National Cyclone Risk Mitigation Project II, funded by GFDRR and the World Bank, which supported the National Cyclone Risk Mitigation Project and the Tamil Nadu and Puducherry Coastal DRR Project by enhancing the participation of women in disaster planning.

By focusing on inclusive community resilience efforts in India it was possible to build a network of disaster management village volunteers and task forces with equal female representation, community collaboration with local governments that include female and minority groups, and involve the Youth in early warnings, search and rescue, first aid, shelter management, and evacuation activities. By involving the entire community in risk identification and management it facilitated a gender-equitable, generally inclusive disaster preparedness and plans and provide a sense of collective responsibility for mitigating vulnerability and risk. Such actions empower the community to respond when an event occurs.

Practical action for the future

Practical, targeted approaches to inclusion in warnings have better outcomes and reach more groups than one-size-fits-all models. So what three essential actions can enhance inclusivity? These are our recommendations:

- Engage diverse people and organisations from the beginning: Finance continual engagement processes for people and organisations to identify and meet their own warning needs – without excluding or inhibiting others.

- Integrate iteration and learning: Take direction from the people and organisations applying warnings. This builds trust and credibility, and helps to integrate long-term warning processes into everyone’s daily lives and governance practices.

- Support initiatives and activities that create an enabling environment: Establish good practices, entry points, and comparable data – but recognise the limitations of safe data collection, replicability, transferability, and scaling.

All three recommendations involve everyone in the warning process: a first mile approach that involves people from the beginning and throughout, rather than just at the last mile.

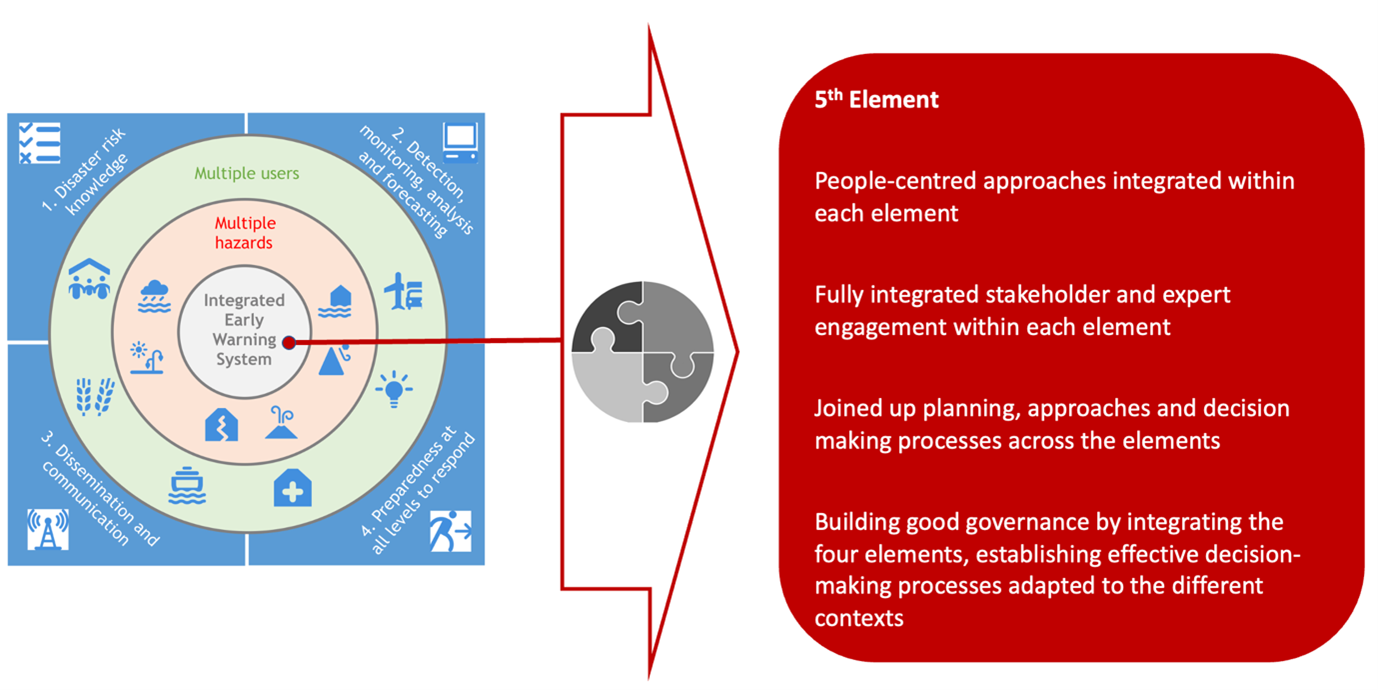

To facilitate this, we propose a fifth element of warnings that enables cross-element collaboration, as well as integration that engages the wider community and the most vulnerable (see figure above). Element-specific accountability should be embedded in the system, and early warning system stakeholders integrated, overseen by an accountable governing body. This oversight should ensure a balanced, coherent plan and program of initiatives to enhance the multi-hazard, intersectional aspect of EWS.

This blog is based on the ‘Designing Inclusive and Accessible Warning Systems: Good Practices and Entry Points’ by Rebekah Yore, Dr. Carina Fearnley, Prof Maureen Fordham, and Prof Ilan Kelman, members of the UCL Warning Research Centre at University College London. We thank: Simone Balog-Way, Ann-Maria Bogdanova, Jana El-Horr, Mirtha Liliana Escobar, Yulia Krylova, Cristina Otano, Makoto Suwa, Zoe Trohanis, and Vladimir Tsirkunov for commissioning this report, and their support and guidance in developing the report.

This study was financed by the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) Umbrella. Lastly, many thanks to the Preventionweb for their guidance, and all the amazing work they do.

Dr Carina Fearnley is Director of the UCL Warning Research Centre and UCL Associate Professor in Science and Technology Studies.

Carina is an interdisciplinary researcher, drawing on relevant expertise in the social sciences on scientific uncertainty, risk, and complexity to focus on how early warning systems can be made more effective, specifically alert level systems.