Heat-related deaths ‘56% higher among women’ during record-breaking 2022 European summer

More than 61,000 people died as a result of searing heat across Europe in the summer of 2022, according to a new study.

The summer of 2022 was Europe’s hottest on record and was characterised by a series of record-breaking heatwaves.

New research published in Nature Medicine explores the link between temperature and human mortality to assess heat-related deaths across Europe during the summer of 2022.

The findings suggest that, for every million people in Europe, 114 died as a result of the 2022 heatwave. The deaths were either direct consequences of the heat or caused by complications to underlying health conditions.

Without adequate adaptation, the authors project the death toll during last year’s summer could become a regular occurrence, with more than 68,000 people dying across the continent on average from the heat every summer by 2030.

The authors find that countries near the Mediterranean Sea – notably Italy, Spain and Portugal – saw the most deaths per million people. The five-week period from mid-July to mid-August was particularly deadly, associated with two-thirds of heat-related summer deaths.

The paper finds that there were 56% more heat-related deaths in women than men, while more than half of heat-related deaths were in people aged 80 and over.

However, an author of the paper tells Carbon Brief that the European heatwave of 2022 was not “exceptional”, in the sense that it follows the warming trend of recent years.

We “cannot know the effect” of a truly “exceptional” heatwave on human mortality rates, he warns, adding that it is crucial for countries to begin taking “preventative measures”.

Record-breaking summer

Europe is the fastest-warming continent in the world.

Average surface temperatures across Europe have been increasing at twice the global average rate since the 1980s, causing heatwaves to become more intense, frequent and long-lasting.

The summer of 2022 was Europe’s hottest on record. Multiple countries recorded highs of 40-43C. As the summer progressed, national temperature records tumbled.

On 19 July 2022, UK temperatures surpassed 40C for the first time on record, when a village in Lincolnshire hit 40.3C – smashing the previous high of 38.7C set in 2019.

A rapid attribution study found that climate change made the UK’s 2022 heatwave 4C hotter and at least 10 times more likely than it would have been without human-caused warming.

Overall, the European summer of 2022 was 1.4C warmer than average. This is 0.3-0.4C warmer than the previous warmest summer, recorded in 2021. The season was also characterised by intense drought, wildfire activity and ice loss from the European Alps.

The authors of the new study use temperature data from the ERA5 land dataset to calculate weekly average temperatures for the summer of 2022, defined as the 14-week period between 30 May-4 September 2022, across 35 European countries.

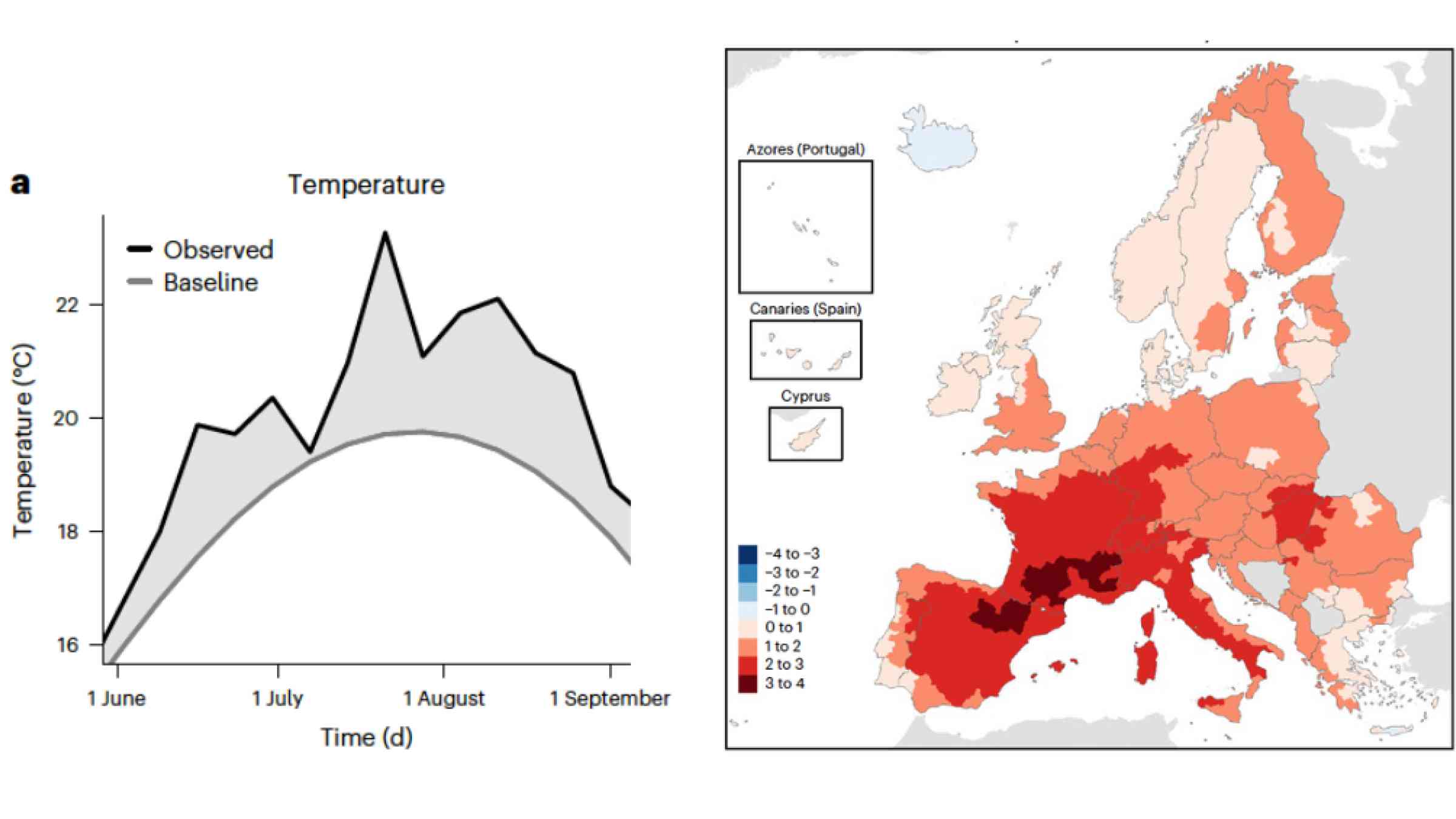

The graph below (left) shows the temperature during the summer of 2022 (black line) compared to the average across Europe for 1991-2020 (grey line). The shading indicates the difference in temperature between the 1991-2020 reference period and 2022.

The map below (right) shows the summer temperature for different European regions in 2022 compared to the average across Europe for 1991-2020. Red shading indicates that the summer of 2022 was hotter than the reference period, while blue indicates that the summer of 2022 was cooler.

The authors find that the temperatures across Europe in 2022 were warmer than the 1991-2020 baseline during every single week of the summer period.

Weekly temperature anomalies in 2022 reached up to 2.33C higher than the long-term average in June, 3.56C higher in July and 2.67C higher in August, according to the study.

The paper adds that, over the whole summer, the warmest summer temperature anomalies were mainly registered in southwestern Europe. Countries including France, Switzerland, Italy, Hungary and Spain all registered temperatures at least 2C higher than the long-term average.

Heat-related deaths

Extreme temperatures can be deadly. More than five million people are estimated to die each year globally due to excessively hot or cold conditions.

During a heatwave, the number of “heat-related deaths” – where exposure to heat either causes or significantly contributes to a death – tends to increase.

For example, people can suffer from direct consequences of heat, such as heat stroke and exhaustion. Those with underlying health conditions can suffer fatal complications due to the excess stress on their bodies.

As climate change drives up average global temperatures, the number of people who die due to complications from extreme heat is rising.

Millions of people die as a result of extreme cold every year. In some countries, such as the UK, the burden of cold weather is currently greater than for heat. But research suggests that, as the planet continues to warm, a growing population exposed to rising temperatures will have an overwhelmingly negative impact on death rates.

The European Statistical Office publishes weekly “death statistics”, which indicate how many people died in 35 different European countries. The office reported “unusually high excess mortality rates” for the summer of 2022, but did not report the cause of death.

The study authors use data from the Eurostat mortality database to produce “epidemiological models” linking exposure to different temperatures to human mortality. They use these models to determine the number of deaths in each region during the summer of 2022 that were associated with extreme heat for different demographic groups.

Marcos Quijal-Zamorano is a doctoral researcher at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health and author on the study. He tells Carbon Brief that extreme heat does not just impact people on the day that they are exposed to the temperatures but also on following days. He says the models used in the study incorporate this “lag effect”.

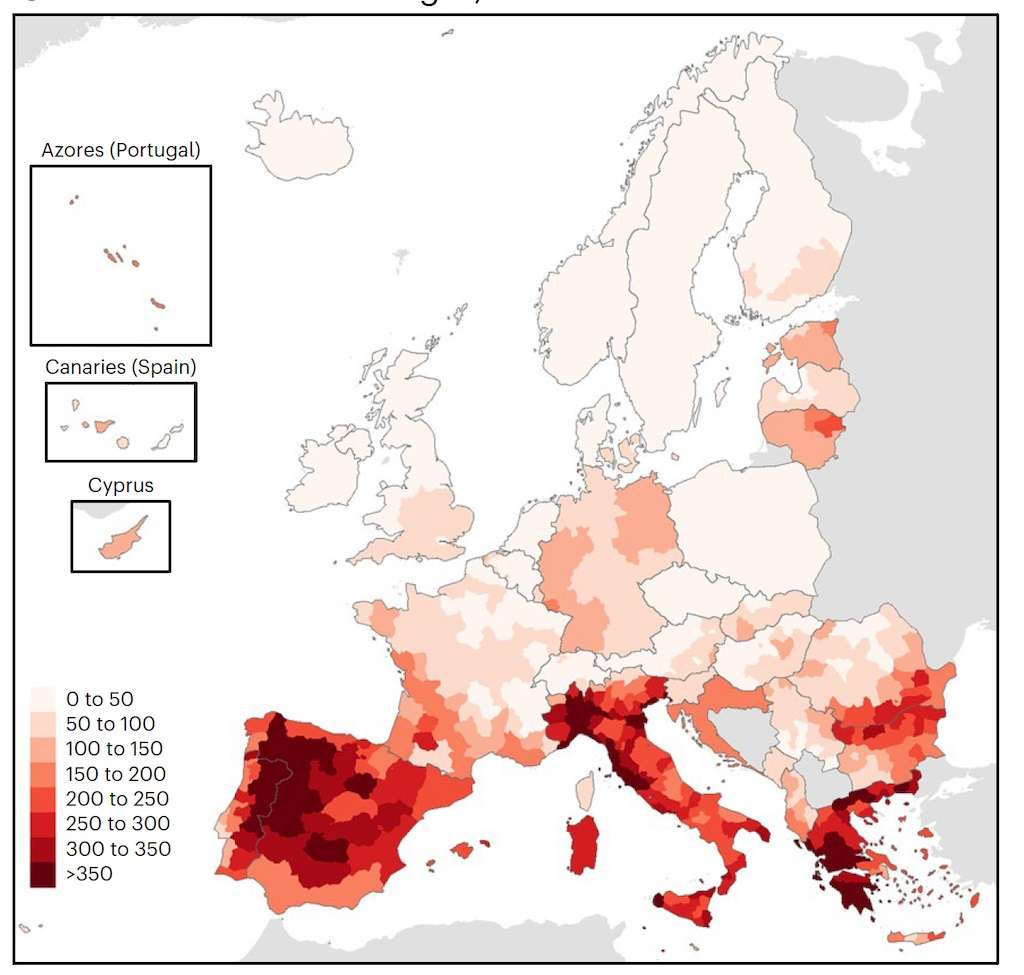

The authors estimate that there were more than 61,000 heat-related deaths in Europe during the summer of 2022. The map below shows the heat-related mortality rate, in deaths per million people, for different regions of Europe. Darker red indicates a higher mortality rate.

The authors estimate that, for every million people in Europe, 114 died as a result of the 2022 heatwave. They add that countries near the Mediterranean Sea, such as Italy, Spain and Portugal, faced the greatest heat-related mortality rates.

The five-week period from mid-July to mid-August was particularly deadly, accounting for around two-thirds of the total summer heat-related deaths, according to the study. It adds that that the week of 18-24 July was the most deadly, associated with more than 11,000 heat-related deaths.

Dr Ana Vicedo-Cabrera is the head of the climate change and health research group at University of Bern and was not involved in the research. She tells Carbon Brief that “the use of weekly mortality temperature is new”, and explains that it may underestimate the number of heat-related deaths.

This is because by taking temperature averages over an entire week, the impacts of short-term spikes in temperature will not be captured. The paper explains that extreme heat “generally does not last for more than five days”.

Vulnerability

Extreme temperatures do not impact everyone equally.

Some groups face greater risks of health complications from extreme temperatures, such as elderly people who are generally less able to regulate their body temperatures.

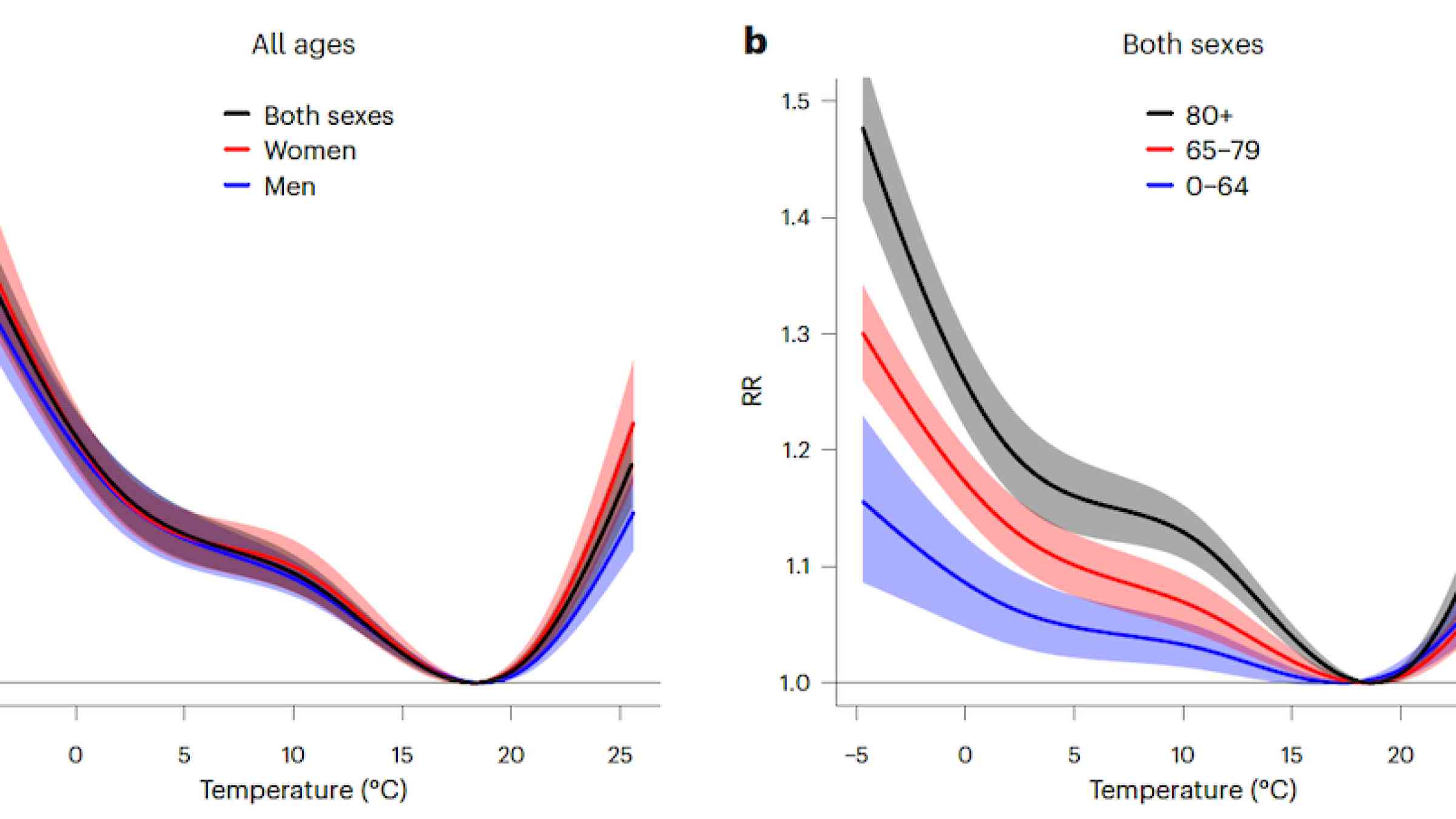

The charts below from the new study show an individual’s risk of death due to exposure to different temperatures. The lowest point on the curve indicates the optimum temperature, when people are at lowest risk of physiological harm from heat. This is between 17-19C across the different demographic groups and exposure to temperatures either side of the optimum increases an individual’s risk of death, the paper notes.

The chart on the left shows the difference in risk of exposure to different temperatures for women (red) and men (blue), with the average shown in black. The chart on the right shows the risk for people aged 0-64 (blue), 65-79 (red) and 80+ (black). Shading shows the 95% confidence interval.

Using this relationship, the authors calculated how many deaths during the 2022 European heatwave were associated with the extreme heat for different demographic groups. These are shown in the table below as the number of deaths per million people.

The findings suggest that relative to the population, there were 56% more heat-related deaths in women than in men during the summer of 2022. The authors also find that the death toll “steeply increased with age”, with more than half of people who died during the heatwave (36,848) aged 80 and over.

The study shows that countries across Europe “need to improve heat health plans and heat adaptation” that “target women and the elderly”, Dr Chloe Brimicombe, a postdoctoral researcher studying climate change and health at the Wegener Center Uni Graz, tells Carbon Brief.

Warming climate

The new study also looks back at the past few decades of European summers to put the 2022 heatwave into context.

The summer of 2003 was the hottest ever recorded at the time, with average temperatures in many countries as much as 5C higher than usual. More than 70,000 people died as a result of the extreme high temperatures, which research showed climate change had made twice as likely.

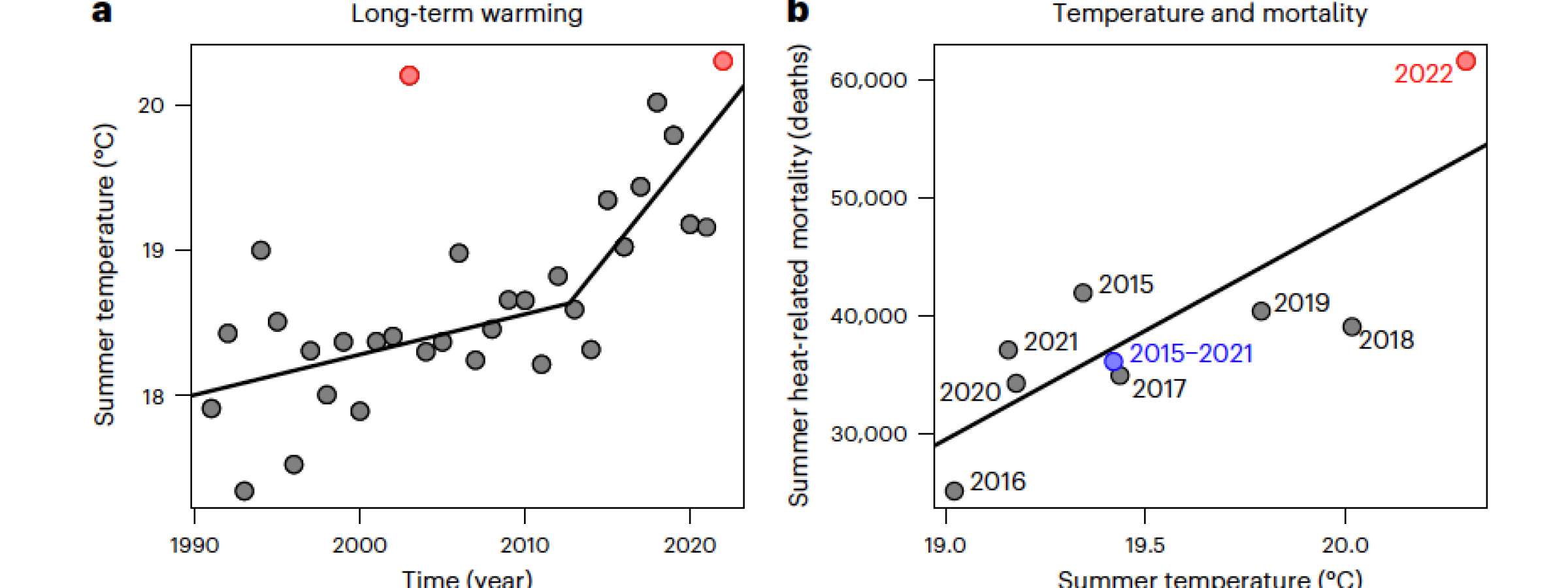

The plot below (left) shows a time series of summer mean temperatures averaged over Europe. The red dots indicate the summers of 2003 and 2022.

The straight lines show the trends in summer temperature in Europe over 1991-2012 and 2013-22, showing that warming has accelerated in the last decade. The trend line does not include the year 2003 because, according to the study, heat mortality during this year was “exceptional”.

The plot below (right) shows the link between summer average temperature and summer heat-related mortality. The straight line shows the trend over 2015-22.

The paper notes that “although summer mean temperatures in 2022 followed the trend observed in the last decade, this was associated with an increase in 25,561 summer heat-related deaths compared to 2015–2021”.

The authors estimate that every increase of 1C in summer temperature since 2015 is associated with more than 18,000 extra heat-related deaths. This equates to more than 35 extra summer heat-related deaths per million people for each 1C rise in summer temperature.

Extrapolating forwards, the authors estimate that if countries do not adapt to the changing conditions, an average of more than 68,000 deaths could be expected every summer by 2030 – and more than 120,000 by 2050.

The heatwave of 2003 was “an exceptionally rare event” which highlighted the “shortcomings” or “inexistence” of heat prevention plans at the time, as well as the fragility of healthcare systems, the new study says.

By contrast, Quijal-Zamorano tells Carbon Brief that the summer of 2022 was not “exceptional”, as it followed the warming trend set by previous summers.

We “cannot know the effect” of another “exceptional” heatwave, Quijal-Zamorano says. But the study emphasises the importance of implementing adaptation measures to avoid the worst impacts of extreme heat.