How to generate relational information to inform a systemic perspective on risk?

This is the seventh in a series of eight articles co-authored by Marc Gordon (@Marc4D_risk), UNDRR and Scott Williams (@Scott42195), building off the chapter on ‘Systemic Risk, the Sendai Framework and the 2030 Agenda’ included in the Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2019. These articles explore the systemic nature of risk made visible by the COVID-19 global pandemic, what needs to change and how we can make the paradigm shift from managing disasters to managing risks.

Nora Bateson

Complexity vexes the traditional problem-solving model, which separates problems into singularly defined parts and solves the symptoms. The COVID-19 pandemic or the climate and ecological crises are pressuring policymakers to try new approaches to meet today’s challenges. But none of these “wicked problems” can be understood with reductionist approaches alone.

In other words, the deliberate simplification of a problem and its causes - by removing it from its contexts - renders the understanding and ensuing policy responses or solution either incomplete or obsolete. The issues raised by the COVID-19 pandemic are wrapped in contextual interdependencies that require an entirely different approach in assessment and action.

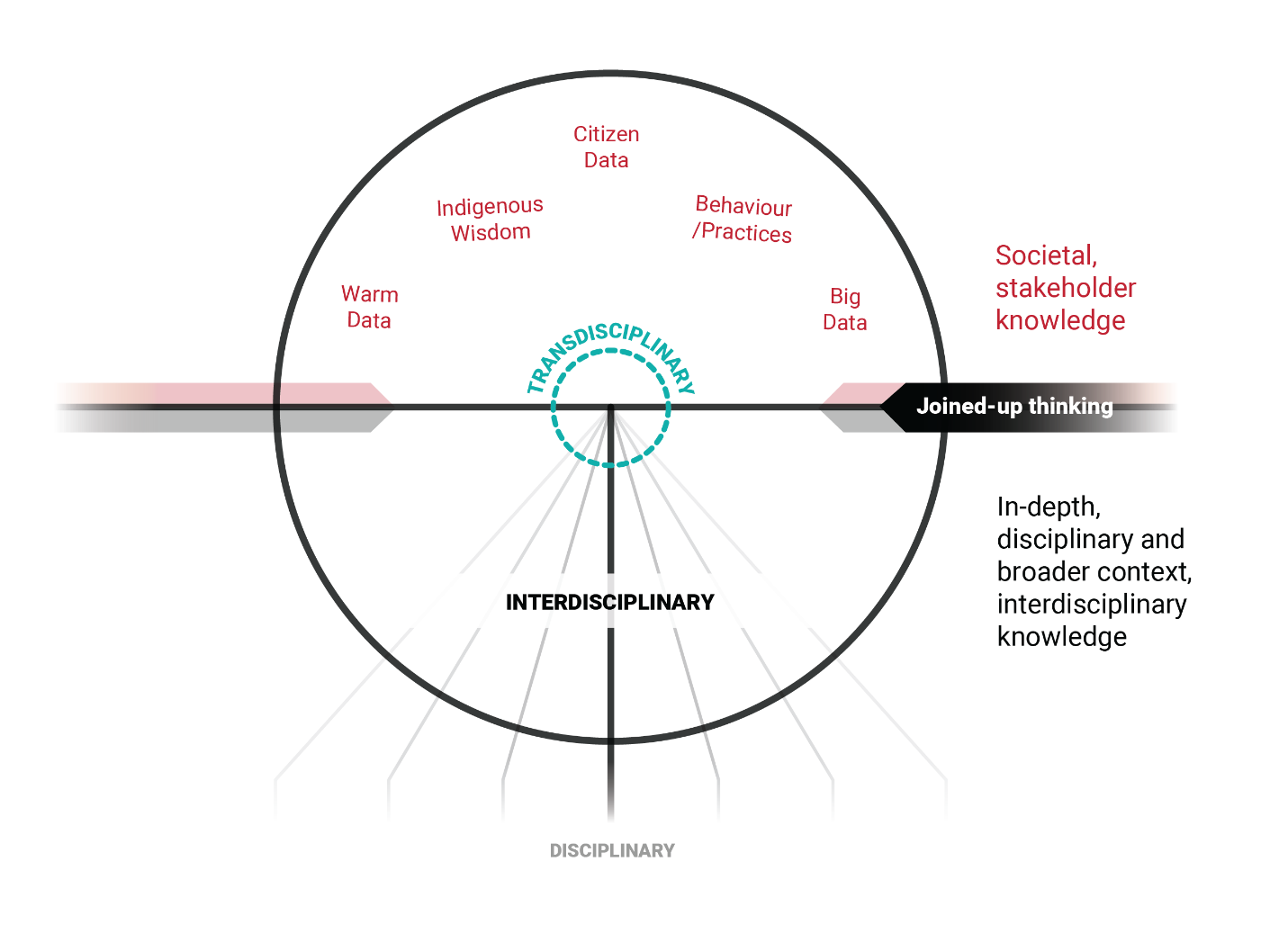

Most current scientific research tools and methodologies pull “subjects” from their contexts to derive detailed, specialized, quantifiable information. We need a wider practice of science to also use information derived from interrelationships and interdependencies within and across systems. For now, the cultural habit of de-contextualizing information, or reductionism, is the standardized, authorized and empirical norm.

To make more appropriate assessments of risks - arising out of multi-causal circumstances – we need observations that can address this complexity. The decisions on what actions to take, by whom and with what resources, are decisions based upon information about the situation or event. If that information cannot hold the appropriate complexity, these decisions will rely on inadequate knowledge, resulting in greater loss and damage – economic, human and ecological.

Transcontextual responses

Risk creation and its realization in complex systems do not remain in one sector at one time. Yet current institutional structures mitigate these complex issues by attending only to what is within their specific jurisdiction. Health crises remain in the realm of health ministries, while economic issues are under the separate attention of ministries of finance or employment. Likewise, ecological risks overlapping with cultural or political risks are still, in most cases, considered in parallel within the ministry of environment. Yet, as evidenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, we must research and better understand the relational interdependence of these phenomena.

We need research bridges and increased communication across societal systems. This is particularly true of public service systems. Lack of communication and contextual perspective (among systems such as education, health, transportation and communication) can increase community-level vulnerability during complex, dynamic systemic risk events. Connection and increased contact between such sectors will make communities more robust and resilient to long-term risks and sudden onset emergencies. The development of relational information approaches can cultivate the relationships among sectors. This strengthens inter-system interaction and collaboration, both within and across countries.

Relational information

'Relational information' describes how parts of a complex system (for example, members of a family, organisms in an ocean reef system, departments of an organization or institutions in a society) come together to give vitality to that system.

Relational information describes the interplay and vital relationships of the parts of a system in context. Other information will describe only the parts. For example, to understand a family, it is not enough to understand each family member. You must also understand the relationships between each of them. This is the relational information. This relational information (also known as 'warm data') helps to better understand interdependencies and improve responses to issues located in relational ways to each other within complex systems.

This is particularly important in understanding the realisation of a complex systemic risk such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Because such an event includes multiple systemic risks across many living systems and contexts - in health, ecological, economic, and education systems and many more. Attempting to suppress complexity (or de-contextualizing) gives specific information that can generate mistakes. In contrast, relational information gives a more coherent understanding of the complex nature of the systems.

Systemic consequences (and consequences of consequences) are easily disconnected from their networks of causation. In so doing, the importance of the relationships among contexts can disappear. Context includes the relational processes that come together to produce a given situation. In fact, most complex situations or systems are 'transcontextual', meaning there is more than one context in play. Transcontextual, relational information brings together multiple forms of observation, from multiple perspectives.

In recognition that information comes in many forms, a relational information lab (or warm data lab) brings together on-the-ground “wisdom” from locals, art and culture, personal stories and the voices of many generations in a series of transcontextual conversations and exchanges. The task of generating relational information is not only to incorporate details and data points, but also to highlight relationships among the details as well, at many scales simultaneously.

Around the world, researchers, governments, and public service professionals already use contextual or relational information in the form of warm data. This is particularly helpful to assess complex situations and identify preventive approaches or responses to complex community (or health) crises requiring expertise that spans a breadth of contextual conditions.

When applied to specific local contexts and fields, scenarios using warm data can be useful to involve local stakeholders and decision makers in a transdisciplinary environment – a collaborative laboratory or “collaboratory”. The approach allows the production of alternative futures that are robust to all the relevant uncertainties and complexities. A set of scenario exercises can help to identify stakeholder preferences, motivations, scale-specific trends and drivers, and most importantly, add the local contexts needed for the modelling exercises to formulate appropriate, timely and proportionate policy responses and solutions.

Changing patterns of interaction at local levels using transcontextual knowledge processes

The natural extension of the above process is bridge-building across systems, across silos. This is a step towards forming collaborative decision-making bodies at local levels. This can bring together people from different, but interdependent fields to explore and energize or regenerate local community vitality. As these community groups form and exchange knowledge, new communication patterns begin to emerge, linking otherwise separated sectors of experience.

The place-based solutions that emerge from the collaborative development of contextual warm data lend themselves to self-organizing around actions that are co-created, with local ownership of data, risks and solutions. By providing context, warm data is a metashift that generates connection, communication and action. It unlocks new ways to address complexity through a systemic perspective, not a siloed perspective. Drawing from collective intelligence and engaging in mutual learning can quickly increase local capacity to deal with even the most complex, dynamic systemic risk challenges

When human interaction occurs in this way, across contexts, the interdependency becomes plain. For example, food cannot be separated from economic, nor even political, systems. Neither can it be separated from culture, nor health, nor identity. The solutions in complex systems lie in the recognition of a collective response. No single response is enough to address a complex problem like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Warm data is the overlap across systems and is produced by groups of people, either in-person or online, with enquiry practised in crossing contextual frames, sense-making and finding patterns. The lens of contextual enquiry and transcontextual research not only brings disciplines together but also many other forms of knowledge - including the place-based wisdom of local practitioners, as well as cultural and indigenous sensitivities.

We need structures and approaches that can bring forward relational information that presents the contextual interlinking of the potential impacts of disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic as they are felt at the individual level within wider global contexts.

When superficial solutions are implemented to provide answers to problems in complex systems, the problems proliferate. Developing the capability for transcontextual understanding and decision-making from a systemic perspective is far more effective. The benefits are then felt across multiple sectors simultaneously, including at municipal and national levels of government.

The next and final article in this series (#8 of 8) introduces the United Nations response to the need for improved understanding and management of the systemic nature of risk incorporating collective intelligence and relational information. The Global Risk Assessment Framework (GRAF) aims to work across all scales and all typologies of risk. Including complex, systemic risk events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. It is in service of the needs of people across the world to engage with complex systems. And to support them to make better decisions both in the short- and the long-term.