|

Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2011

Revealing Risk, Redefining Development |

|

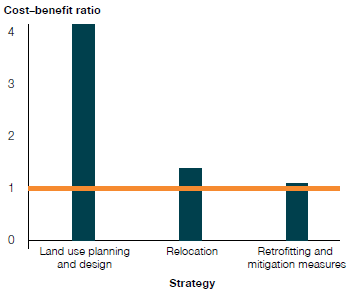

5.3.3 Reducing the retained risksAs highlighted in the case of Colombia, even if it had insured its catastrophic risk the government would have to invest approximately US$200 million per year if it were to compensate for the losses for which it is responsible.14 In general, therefore it is much more cost-effective for governments to invest in reducing the more extensive risk strata (i.e., below the deductible amount) using a mix of prospective and corrective disaster risk management strategies. Figure 5.9

Comparison of the cost–benefit ratios of improved land use planning, relocating exposed settlements, and retrofitting and mitigation measures in Colombia

(Source: Adapted from ERN-AL, 2010

ERN-AL. 2010. Seismic risk assessment of schools in the Andean region in South America and Central America. Bogotá, Colombia, Barcelona, Spain, and México DF: Consortium Evaluación de Riesgos Naturales – América Latina. ). Figure 5.10

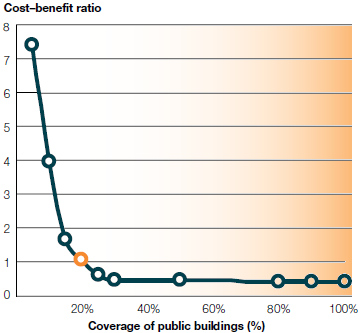

Cost–benefit ratio of reinforcing the portfolio of public buildings in Mexico

(Source: ERN-AL, 2010 ERN-AL. 2010. Seismic risk assessment of schools in the Andean region in South America and Central America. Bogotá, Colombia, Barcelona, Spain, and México DF: Consortium Evaluación de Riesgos Naturales – América Latina. ). Figure 5.11

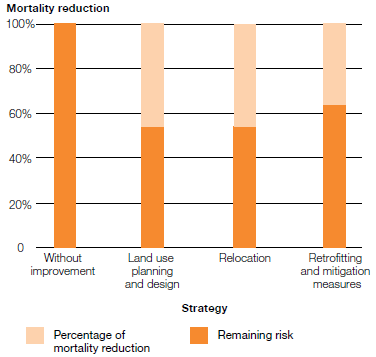

The percentage reduction of mortality in Colombia due to different risk reduction strategies

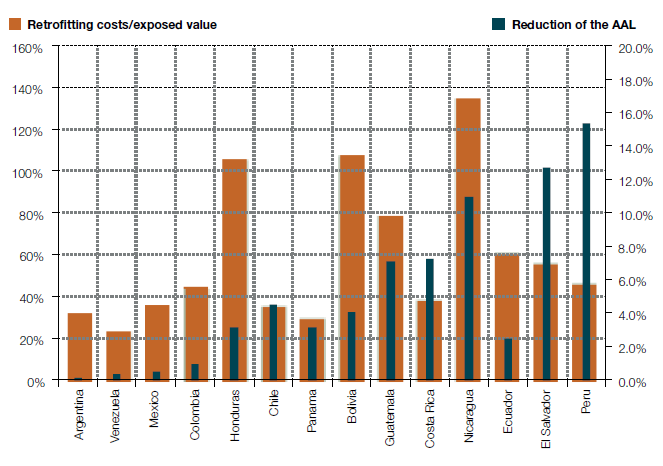

(Source: ERN-AL, 2010 ERN-AL. 2010. Seismic risk assessment of schools in the Andean region in South America and Central America. Bogotá, Colombia, Barcelona, Spain, and México DF: Consortium Evaluación de Riesgos Naturales – América Latina. ). In Colombia, as in the other pilot countries, land use planning and improved building standards generate the largest ratio of benefits to costs (approximately 4 to 1). Although corrective risk management produces a positive benefit to cost ratio, it is clear that it is far more cost-effective to anticipate and avoid the buildup of risk than to correct it (Figure 5.9). Corrective risk management, however, is far more cost-effective when it is concentrated on the most vulnerable part of a portfolio of risk prone assets. In Mexico, for example, the ratio of benefits to costs when investing in strengthening risk-prone public buildings is far more attractive when it is focused on the most vulnerable 20 percent of the portfolio (Figure 5.10). This carries a powerful message and opportunity for governments. Corrective risk management investments can be very cost-effective if they concentrate on retrofitting the most vulnerable and critical facilities rather than being spread widely over many risk-prone assets. These measures can be even more attractive when the political and economic benefits of avoiding loss of life and injury, decreasing poverty and increasing human development, are taken into account. Saving human lives, for example, may be a more powerful incentive for DRM than pure cost-effectiveness. In Colombia, better prospective and corrective investments in risk management would both lead to significant reductions in mortality (Figure 5.11). Although illustrative, these calculations of costs and benefits are likely to be too conservative. They do not take into account the cost of downstream outcomes, such as increased poverty, reduced human development, increased unemployment and inequality. Schools are a politically attractive target for investment in risk reduction. However, if direct economic costs were the only consideration, only four countries in Latin America would opt to retrofit schools for earthquake safety (Box 5.8). Whereas decisions to invest in retrofitting schools should be relatively easy to defend, they are nevertheless made against a backdrop of complex political, social and financial dynamics. Structural reinforcement alone may be costly, and programmes that include both infrastructure and equipment upgrading, and involve the local community, can be more attractive. When the costs of retrofitting different building types are taken into account, the three countries where retrofitting would be most cost-effective are Costa Rica, El Salvador and Peru. In Bolivia (Plurinational State of), Honduras and Nicaragua, the estimated retrofitting costs are greater than the costs of replacing the schools. In Argentina, Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), the expected reduction of average annual loss would not justify the investment. These calculations of cost-effectiveness did not take into account injury and loss of life, nor did they value education and its loss. When children’s lives are at stake, there may be a strong imperative to retrofit, even when the expected savings in lost educational infrastructure do not match the costs. In addition, given the effects of education on well-being and economic growth, demands for child safety, and the protection of public investments in education, the reduction of seismic vulnerability of educational facilities becomes a matter of priority. Box 5.8 The costs and benefits of school retrofitting in Latin America

Damage and destruction of schools by earthquakes, floods and tropical cyclones leads to an unacceptable loss of children’s and teachers’ lives, wasting valuable public investment in social infrastructure and interrupting the education of those who need it most.15 In the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, it was estimated that 97 percent of the schools in Port-au-Prince collapsed (Fierro and Perry, 2010 Fierro, E. and Perry, C. 2010. Preliminary reconnaissance report - 12 January 2010 Haiti earthquake. University of California, Berkeley, USA: The Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center (PEER). ). In the earthquake in south Sumatra in 2009 more than 90,000 students were left without a school. As highlighted at the beginning of this chapter, although the destruction of schools in major earthquakes tends to attract media coverage, almost as many schools are damaged and destroyed in extensive disasters.. School safety has been established as a disaster risk reduction priority,16 but it is simply not cost-effective to retrofit all vulnerable schools. For example, in Bogota, Colombia, an assessment identified 710 schools built before 1960, of which 434 had a high vulnerability to earthquakes. Limited budgets meant that not all schools could be retrofitted and priority was given to the 201 schools that showed a positive cost–benefit ratio (Coca, 2007 Coca, C. 2007. Evaluación diagnóstica de la gestión del riesgo del sector educativo en el marco de la sostenibilidad urbana de Bogotá. MSc Thesis.Bogota: National University of Colombia. ).. A recent study (ERN-AL, 2010 ERN-AL. 2010. Seismic risk assessment of schools in the Andean region in South America and Central America. Bogotá, Colombia, Barcelona, Spain, and México DF: Consortium Evaluación de Riesgos Naturales – América Latina. ) of earthquake vulnerability of schools in Latin America calculated the

average annual loss for each country, taking into account earthquake hazard, the number of exposed

schools, and their structural vulnerability both with and without retrofitting (Figure 5.12).

In Bolivia, Honduras and Nicaragua, the retrofitting costs are greater than the value of exposed schools. In countries like Argentina, Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela, the expected reduction in average annual loss is not significant. Costa Rica, El Salvador and Peru are the countries with higher expected reductions in average annual loss and relatively low costs of retrofitting.. Figure 5.12

The costs and savings associated with retrofitting schools in Latin America  (Source: ERN-AL, 2010 ERN-AL. 2010. Seismic risk assessment of schools in the Andean region in South America and Central America. Bogotá, Colombia, Barcelona, Spain, and México DF: Consortium Evaluación de Riesgos Naturales – América Latina. ; Valcarcel et al., 2011. Valcarcel, J.A., Mora, M.G., Cardona, O.D., Pujades, L.G., Barbat, A.H. and Bernal, G.A. 2011. Analisis de beneficio costo de la mitigación del riesgo sísmico de las escuelas de la región andina y de centro américa. 4a Conferencia Nacional de Ingenería Sísmica, 4CNIS. Granda, Spain: Asociación Espanola de Ingenería Sísmica. ). Notes 14

In fact the losses due to extensive disasters affecting

more than 700 municipalities in Colombia during

the 2010–2011 rainy season have been estimated in

US$5.4 billion (Cardona, 2011 Cardona, O.D. 2011. Anticiparse al peligro no es una opción, es una obligación. UN Periódico No. 141. Bogota, Colombia: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.. ) far exceeding available

contingency funds and lines of credit. As a result the

government has had to consider selling 25 percent of

the capital of national energy company ECOPETROL

to cover the gap (for more information see www.unperiodico.unal.edu.co/dper/article/anticiparse-alpeligro-no-es-una-opcion-es-una-obligacion).15

An empirical analysis on a panel of 19 OECD

countries observed from 1971 to 1998 has found a

robust positive correlation between expenditures on

health and education and GDP growth (Beraldo et al., 2009 Beraldo, S., Montolio, D. and Turati, G. 2009. Healthy, educated and wealthy: A primer on the impact of public and private welfare expenditures on economic growth. The Journal of Socio‐Economics 38 (6): 946–956. ). Evidence also suggests that public expenditures

influence GDP growth more than private expenditures.

In particular, estimates show that a 1 percent

increase in total educational expenditure growth rate

would increase the per-capita GDP growth rate by

0.03 percent, with most of this effect coming from

public expenditure (Ibid.). 16

Global UN campaigns on safe schools are evidence of

this, such as the 2006–2007 ‘Disaster Risk Reduction

begins at School’ campaign, or the more recent ‘A

million schools and hospitals safe from disaster’

initiative within UNISDR’s ‘Making Cities Resilient’

campaign. |

|