|

Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2011

Revealing Risk, Redefining Development |

|

4.6 Incorporating DRM into national planning and investment

Most countries continue to have difficulty integrating risk reduction into public investment planning, urban development, environmentalplanning and management, and social protection.

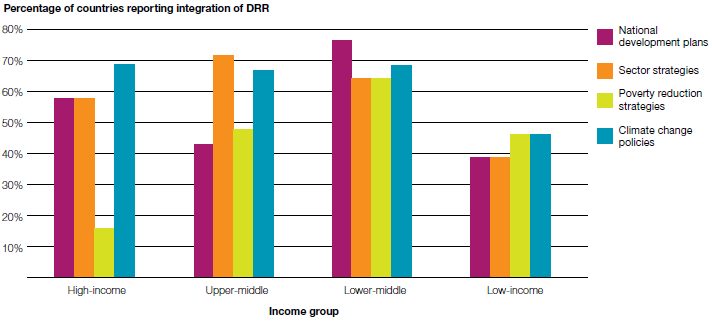

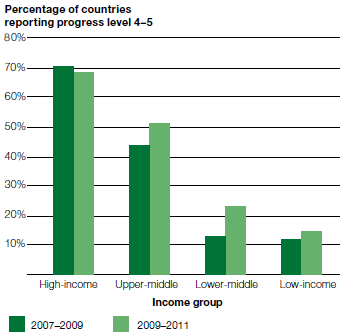

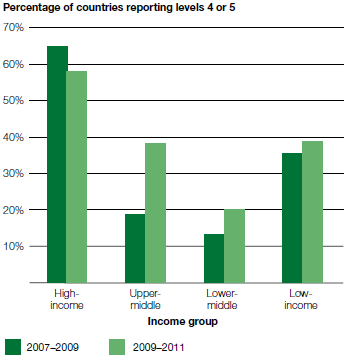

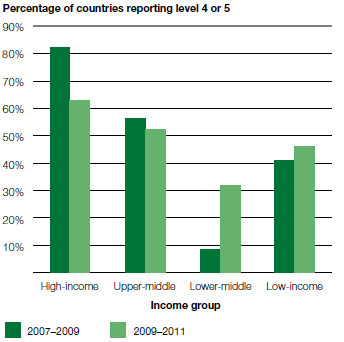

If development planning and investments fail to incorporate risk reduction, a country’s stock of policiesrisk will continue to grow. Yet, most countries and territories reported least progress in this area of the HFA. Antigua and Barbuda, Bolivia, Botswana, Georgia, Lesotho, Mauritius, Mexico, Monaco, Occupied Palestinian Territories, Paraguay, Saint Lucia and Togo are just some of the countries struggling to reduce underlying risk. But even countries that have attained some success, such as France, Germany, Portugal and the United States of America, score their efforts as low in this area. The 2009–2011 review shows little or no advance on the 2007–2009 results. Most countries continue to have difficulty integrating risk reduction into public investment planning, urban development, environmental planning and management, and social protection . Some countries have yet to recognize climate change adaptation as an important area. A number of high-income countries or territories, such as Croatia, Czech Republic, and the Turks and Caicos Islands, reported that climate change is not yet on their policy agendas and, as a result, increasing climate risk is not taken into account in DRM. However, the majority did report the emergence or strengthening of climate change adaptation projects and programmes: 72 percent globally, with a relatively equal distribution across regions and income classes. Compared with 2007–2009, lower-middle-income countries, such as Bhutan, reported most progress in integrating disaster risk reduction into national development plans and climate change policies (Figure 4.10). However, lower-middle-income countries, reported less substantial progress integrating risk reduction into poverty reduction strategies or other sector strategies that address the underlying drivers of risk. Figure 4.10

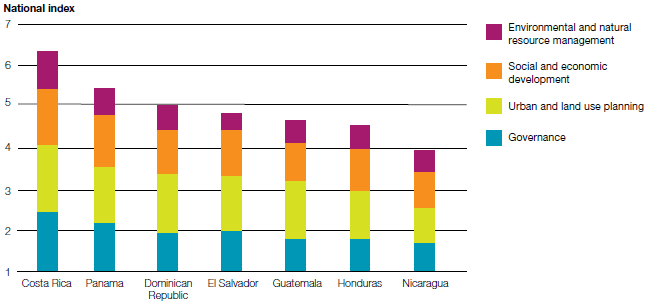

Countries reporting on progress on HFA Priority Area 4  Box 4.6 confirms that countries differ widely in their capacities to address risk drivers, such as badly planned and managed urban and regional development, the destruction of ecosystems, and the pervasive poverty of risk-prone households and communities. Box 4.6 The Risk Reduction Index

The DARA Risk Reduction Index (DARA, 2011 DARA. 2011. Indice de reduccion del riesgo. Análisis de capacidades y condiciones para la reducción del riesgo de desastres. Madrid, Spain: DARA. ) is based on 38 indicators that measure the extent to which

a country is addressing the underlying risk drivers identified in GAR09, and to which it has appropriate and

effective governance arrangements. In a detailed comparison of seven countries in Central America and

the Caribbean, Costa Rica was found to have the strongest risk governance capacities, and Nicaragua the

weakest (Figure 4.11).. The Risk Reduction Index uses data from a large range of well-established indices, including the World Bank’s Governance Index. In preparatory analysis for the Index, a global risk index table for 184 countries was developed (DARA, 2011 DARA. 2011. Indice de reduccion del riesgo. Análisis de capacidades y condiciones para la reducción del riesgo de desastres. Madrid, Spain: DARA. ; Lavell et al., 2010. Lavell, C., Canteli, C., Rudiger, J. and Ruegenberg, D. 2010. Data spread sheets developed in support of the DARA 'risk reduction index: Conditions and capacities for risk reduction'. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. ). This analysis shows that the top six countries

(Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark, Ireland, Norway and Finland) are all high-income countries with strong

governance capacities, and have largely addressed their underlying risk drivers. In contrast, the bottom six

countries (Afghanistan, Chad, Haiti, Somalia, Democratic Republic of Congo and Eritrea) are low-income

countries that are experiencing or have recently experienced conflicts or political crises. These countries

have very weak capacities to address the drivers.. A number of middle-income countries, such as Chile, Barbados and Malaysia, rate relatively highly on the Index, indicating that risk governance capacity is not just a reflection of GDP per capita. Low- and middleincome countries do not have to wait for their economies to develop before they address their disaster risks. Conversely, a number of relatively wealthy countries whose economies depend on energy exports rate lower on the index, including Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Equatorial Guinea and Angola. The in-depth comparison of Central American and Caribbean countries highlighted major differences in capacities not only among countries, but also among different areas of the same country. As well as reflecting widely varying processes of risk construction, this highlighted important differences in perception of both risk and disaster risk management among different stakeholders, and between local and national levels. Surveys, structured around the four drivers of risk identified in GAR 2009, were conducted to inform an index on conditions and capacities for disaster risk reduction.8 Consistent with findings from the 2009 civil society review ‘Views from the Frontline’, government respondents scored governance capacities considerably higher than did members of civil society.9 Poor governance emerged as the driver that conditions all the other underlying drivers. Improving governance was thus emphasized as the single most important priority for reducing disaster risk. Figure 4.11

Risk governance capacities across Central America and the Caribbean  (Source: Adapted from DARA, 2011 DARA. 2011. Indice de reduccion del riesgo. Análisis de capacidades y condiciones para la reducción del riesgo de desastres. Madrid, Spain: DARA. ). Given these different starting points, it is unsurprising that those countries that reported little progress did so from very different perspectives. Some national reports (from Albania and Senegal, for example) reveal a focus on preparedness and emergency management and higher progress in HFA Priority Area 5 (strengthening disaster preparedness) than in other areas. Others, such as Peru, show a sophisticated understanding of the complexities of addressing underlying vulnerabilities and drivers of risk together with a low progress score. Namibia reported that investment into DRM, rather than response and preparedness, is difficult to plan and account for. Greater understanding appears to bring greater awareness of the magnitude of the task. 4.6.1 Investment planningFigure 4.12

Countries reporting substantial progress in assessing disaster risk impacts of infrastructure

Figure 4.13

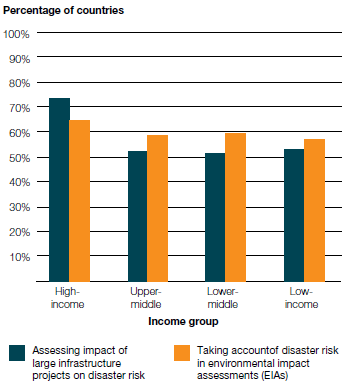

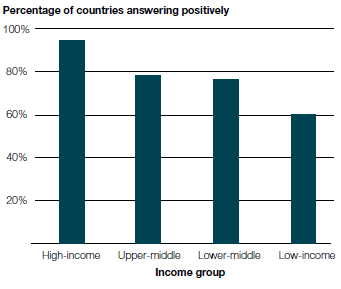

Countries reporting on means to assess disaster risk in development investments

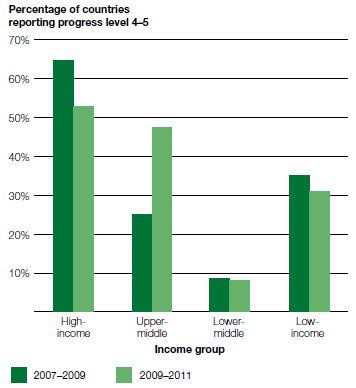

New supporting data for the current reporting period show that countries employ different types of mechanisms to assess disaster risk. As Figure 4.13 shows, while most OECD and other high-income countries directly assessed risks in critical infrastructure projects, low- and middle-income countries seem to rely more on pre-existing environmental impact assessments to fulfil this function. 4.6.2 Urban and land use planningIn the present reporting cycle, lower-middle-income countries reported significant progress in the area of urban development and land use planning compared with 2009. However, there remains a staggering discrepancy between high- and low-income nations, with almost 70 percent of high-income countries and only 15 percent of low-income countries scoring 4 or 5 (Figure 4.14).Figure 4.14

Countries reporting on urban and land use planning: 2007–2009 and 2009–2011

Figure 4.15

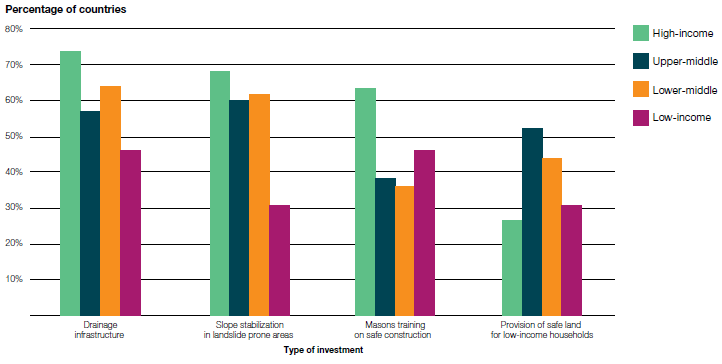

Countries reporting on investments to reduce vulnerable urban settlements

Low-income countries find it harder than higher-income countries to make the investments necessary to reduce urban risk (Figure 4.16). Urban drainage systems, for example, are recognized as an important tool for reducing urban risk but less than half (46 percent) of low-income countries invested in drainage infrastructure in flood-prone areas. Less than a third (31 percent) of low-income countries took measures to counter landslide risk, compared with around 60 percent of lower- and upper-middle-income countries, and 68 percent of high-income countries. A less significant but similar trend was observed for the provision of safe land for low-income households and communities. This finding is consistent with the rapid increase in housing damage in urban areas reported in Chapter 2. Figure 4.16

Countries reporting on DRM investments aimed at reducing urban risks  Some countries have introduced hazard-resistant building regulations only recently. The Syrian Arab Republic, for example, first introduced a seismic code in 1995. Weak implementation and enforcement mechanisms are common problems in countries where most urban development is informal. In addition, reports from several countries and territories reveal the trade-offs internalized in any decision to invest in DRM. For example, Croatia reported pressure from the construction industry to lower standards and codes to reduce overall construction costs, even in hazard-prone areas. 4.6.3 Environmental planning and managementFigure 4.17

Countries’ reported progress and decline integrating DRM into environmental policies

More than 95 percent of lower-middle-income countries have ecosystem protection measures in place, and more than 80 percent of countries globally have mechanisms to protect and restore regulatory ecosystem services. However, a number of countries claimed that existing laws needed stronger legislation or enforcement. For example, Sierra Leone reported that enforcement bylaws need updating to act as effective deterrents. Similarly, Indonesia points out that overlapping responsibilities and legislation on environmental and disaster management result in a lack of synergy and coordination, which hinders enforcement. Timor-Leste, along with several other countries worldwide, is hampered by protective-area legislation that does not take disaster risk into account. 4.6.4 Social protectionBox 4.7 Linking social protection and disaster risk reduction

All of Malawi’s social development

policies are designed and implemented

so as to reduce the vulnerability of at-risk

communities. Its new Social Support policy,

scheduled to be approved in 2011, explicitly

links social protection with disaster risk

reduction. Further, Malawi reported that a

pilot cash-transfer programme, primarily

targeted at orphans and the elderly, has

already had a positive impact on a number of

districts. ERD. 2010. Social protection for inclusive development - A new perspective on E.U. cooperation with Africa. The 2010 European report on development. Florence, Italy: Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute.Draft. ; UNRISD, 2010. UNRISD (United Nations Research Institute for Social Development). 2010. Combating poverty and inequality: Structural change, social policy and politics. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. ). GAR09 highlighted the role of social protection in DRM and Chapter 6 of this report discusses how countries are adapting various instruments designed to increase community and household resilience (Box 4.7). As well as supporting individuals and communities during and after a disaster, social protection is increasingly recognized as a means for increasing pre-disaster resilience.. Figure 4.18

Countries reporting on the use of social protection to reduce vulnerability

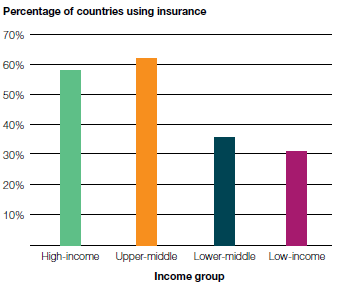

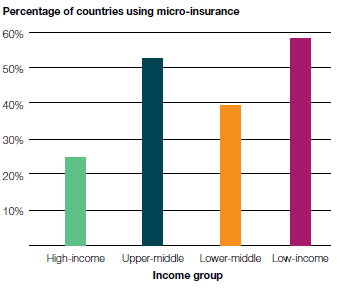

Different instruments scored very differently across income groups. Figures 4.19 and 4.20 show that, on one hand, penetration of crop and property insurance is far higher in highand upper-middle-income countries than in low-income countries. On the other hand, 58 percent of low-income countries use microinsurance instruments, compared with only 25 percent of high-income countries. Low- and lower-middle-income countries and territories such as Bolivia, the Cayman Islands, Côte d’Ivoire, El Salvador, Guatemala, Indonesia, Madagascar, Maldives and Nicaragua all reported no or little progress on the provision of social protection instruments, such as cash transfers or employment programmes that can enhance households’ disaster resilience. Figure 4.19(left)

Countries reporting on the use of crop and property insurance Figure 4.20(right) Countries reporting on the use of micro-insurance

Ecuador is one of few countries that implemented a wide range of social policy instruments as part of their disaster risk reduction strategy. As the country’s Ministry for Agriculture is responsible for a number of these social development programmes, they are tightly linked with livelihoods and asset protection. Figure 4.21

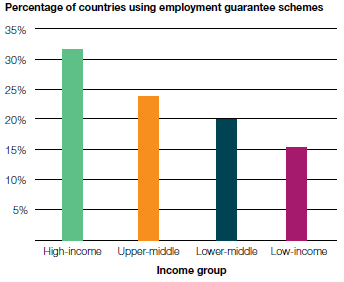

Countries reporting on the use of employment guarantee schemes

Figure 4.22

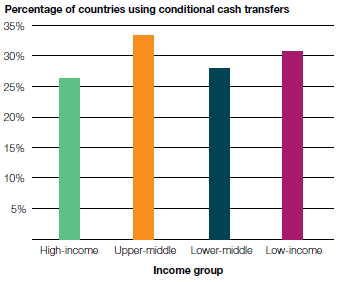

Countries reporting on the use of conditional cash transfers

Only 23 percent of countries globally reported the use of employment guarantee schemes (Figure 4.21). This is unsurprisingly low given that such schemes are perceived as a large burden on national budgets, though this is being countered by evidence from successful and affordable schemes across the globe (see Chapter 6). Conditional cash transfers, although considered more targeted and efficient, are used by only 31 percent of low-income countries, including Burundi, Kyrgyzstan and Zambia (Figure 4.22). Of all the countries that use these instruments, more than half are middle-income countries. High-income countries tended not to use these instruments because their social welfare systems usually operate via pensions, family benefits and other similar mechanisms. 4.7 Strengthening institutional and legislative arrangements

Often national DRM organizations lack the political authority and technical capacity to engage development sectors. A failure to strengthen local governments and make progress in community participation means that the gap between rhetoric and reality is widening.

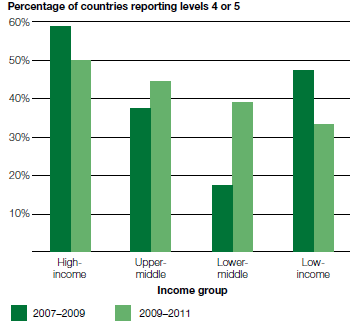

The location within a government of authority for national policy on DRM can critically influence a country’s ability to use national and sector development planning and investment to reduce its disaster risks. National DRM organizations often lack the political authority and technical capacity to engage development sectors. Timor-Leste, for example, failed to generate substantial momentum for DRM in sector ministries because of the relatively isolated and weak position of its National Disaster Management Department. Some countries have made DRM apex bodies of presidents’ and vice presidents’ offices (or placed them within existing apex bodies). These include Myanmar, where the National Disaster Preparedness Central Committee is chaired by the prime minister; Nepal, which has moved the responsibility for its National Strategy for Disaster Risk Management under the chairmanship of the prime minister; and Botswana, where the National Disaster Management Office is an apex of the vice president’s office. However, it is unclear whether this has improved the coordination of national or sector development planning and investment. There is little evidence of countries locating responsibility for DRM in their economic and financial planning ministries. Only the United Republic of Tanzania reported such a move, developing its Zanzibar Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty for 2010–2015 through the Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs. This has provided a strong push for DRM, from reviewing and harmonizing laws and policies to infrastructure improvements, capacity building and community-based disaster preparation. Several countries have spread the various functions of DRM across different levels of governance. In Nigeria, for example, a central coordinating body chaired by the vice president leads policy development, monitoring and response; at the lower levels of governance, states set up their own emergency management agencies with responsibility for disaster prevention, education and awareness raising, and local response preparedness. A number of countries reported major coordination challenges where DRM responsibilities are distributed across sectors. In addition, where responsibilities are spread horizontally and vertically, new laws and strategies may sit awkwardly next to outdated statutes and policies developed within sector departments. To address this challenge, Morocco, for example, has set up a working group with the Ministry of the Interior to conduct a joint revision of outdated laws and policies. However, as reported by Namibia, updating national policies and disaster management plans according to new legislation can be a slow process. 4.7.1 Limited local capacity and actionThe central role of local governance in DRM is now acknowledged by most countries. However, across all indicators relating to decentralization, a failure to strengthen local governments and make progress in community participation means that the gap between rhetoric and reality is widening (Figure 4.23).Figure 4.23

Countries reporting substantial progress (level 4 or 5) in community participation and decentralization for DRM

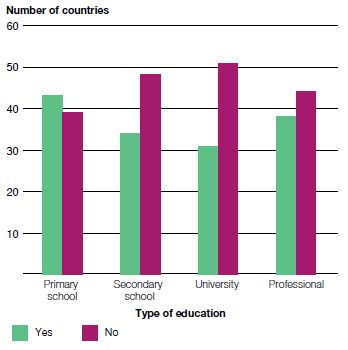

4.7.2 Very limited progress in public awareness and education for DRMPublic awareness of risks and of how to address them is a key to strengthening accountability and ensuring that disaster risk management is implemented. Yet, only 19 countries reported substantial progress in this area, with 63 indicating weak or average progress. Anguilla, Côte d’Ivoire, Kyrgyzstan, Poland and the Seychelles advanced least in this area, compared with all other HFA priority areas. Most countries reported significant efforts in campaigns to raise public awareness, including outreach to local governments and risk-prone communities. Despite these advances, around 60 percent of countries that rated themselves as making good overall progress, reported weak or average progress on making available information on disasters and disaster risk reduction issues.China was a notable exception, reporting substantial and comprehensive progress on the availability of risk information, on developing a countrywide public awareness strategy, and on integrating DRM into school curricula (from primary to tertiary levels). As Chapter 7 of this report highlights, access to information and risk awareness drive social demand for disaster risk reduction. If countries have no established mechanism for accessing disaster risk information, their citizens will find it difficult to demand more effective risk reduction. Figure 4.24

Number of countries reporting on the integration of DRR into school curricula(

Another area where progress has been slow is in research; in particular, research on improved multi-risk assessments and cost–benefit analyses. Three-quarters (63 out of 82) of the reporting countries reported little or average progress in this area, with only 19 countries indicating substantial progress. Furthermore, most countries curricula(85 percent) reported no research into the economic costs and benefits of disaster risk reduction. 4.8 Regional progress

Many regional inter-governmental organizations have successfully developed regional risk reduction frameworks and strategies. However, these often emphasize risk management over risk reduction and it has been difficult to engage non-governmental actors meaningfully in these processes. Disaster risks associated with major hazards are often a regional concern. Most (74 out of 82) countries participated in regional and sub-regional DRM programmes and projects, and many countries also have action plans addressing trans-boundary issues. Many regional inter-governmental organizations have successfully developed regional risk reduction frameworks. More than three-quarters (63) of the countries participated in the development of regional strategies – with SOPAC in the Pacific, ASEAN in South-East Asia, CDEMA in the Caribbean, CEPREDENAC in Central America, the African Union and NEPAD in Africa,10 amongst others, all developing regional disaster risk reduction frameworks. The most recent success was provided by the Council of Arab Ministers Responsible for the Environment (CAMRE), which adopted the Arab Strategy for Disaster Risk Reduction 2020, endorsed by heads of state in January 2011. The Incheon REMAP initiative is another example of an innovative approach to regional learning and cooperation (Box 4.8). Box 4.8 An Asian roadmap to cope with weather-related risks

In October 2010, 50 Asian and Pacific region governments agreed to make risk reduction part of their

national climate change adaptation policies and jointly address the increase in severe weather events.

The Fourth Asian Ministerial Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction approved a five-year regional

roadmap, the Incheon REMAP, which brings together climate-sensitive risk management systems at the

regional, national and community levels. This new regional framework recognizes disaster risk reduction as a key tool for climate change adaptation. The main components include raising awareness on weather-related hazards, sharing information through new technologies, and integrating disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation into sustainable development policies. The roadmap also promotes the sharing of information on, and new technologies related to, emerging risks and vulnerabilities. Goals include improving national hydro-meteorological capacities to increase preparedness, forecasting, risk transfer, and early warning and evacuation systems, as well as incorporating disaster risk into urban development for the most exposed communities. The roadmap’s progress will be reviewed at the next Asian Ministerial Conference, to be held in Indonesia in 2012. Initiatives in Europe have resulted in agreement on a comprehensive strategy and implementation plan for the European Commission’s support to disaster risk reduction. Moreover, the Council of Europe has taken steps toward a joint European approach to managing risk in member states (Box 4.9). Box 4.9 The European and Mediterranean Major Hazards Agreement

Created in 1987, the Council of Europe’s European and Mediterranean Major Hazards Agreement

(EUR-OPA) is a platform for co-operation between European and southern Mediterranean countries in

the field of major natural and technological disasters. Its remit covers the knowledge of hazards, risk

prevention, risk management, post-crisis analysis and rehabilitation. EUR-OPA’s plan of action and activities are aligned with the priorities of the HFA and support the development of national platforms. Since 2008, in close collaboration and coordination with the UNISDR Europe Regional Office, EUR-OPA has supported the establishment of the European Forum for Disaster Risk Reduction (the acting regional platform for DRR in Europe), which was officially launched in 2009 and is composed of the European HFA focal points, national platform coordinators and regional organizations. In the past four years, the activities carried out by EUR-OPA focused on the drivers of risk and disasters. Moreover, following the EUR-OPA 12th Ministerial Session in September 2010 in Saint Petersburg, Russia, a new five-year plan (2011–2015) was adopted. The new plan seeks to address persistent vulnerabilities and envisages the involvement of citizens in building resilience to reduce disaster risk and adapt to climate change. The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) has agreed on a Comprehensive Regional Framework on Disaster Management, and has established its organizational structure. Despite this success, SAARC reported that although constitutional commitment has been attained, comprehensive or substantial achievements are still elusive (Box 4.10). Box 4.10 The challenges of addressing trans-boundary risks in South Asia

The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) reported that the process of agreeing on the Comprehensive Regional Framework on Disaster Management was “painstakingly slow” and was hampered by limited commitment of member states, limited resources and the competing priorities and responsibilities of different government departments. The fact that the Framework is not legally binding is seen as a major impediment to effective implementation. Despite these challenges, SAARC has developed nine regional roadmaps, which cover coastal, marine and urban risk, and risks associated with earthquakes, landslides and droughts. Information-sharing is another challenge. Bilateral exchange of information already exists on, for example, rainfall and river discharge data. Regionally, however, there is a reluctance to share data and information on trans-boundary hazards and vulnerabilities in a systematic and ongoing manner. SAARC sees this as a major gap in current progress and reports on three main challenges to trans-boundary risk assessment in South Asia: scarcity of quality data; lack of coordination between different and often competing ministries and member states; and lack of adequate financial and human resources (including technical capacity). These impediments mean that although the region has succeeded in getting high-level commitment to carrying out trans-boundary assessments, this has yet to translate into practice. The regional progress report of the Arab States also highlights a lack of ongoing sub-regional and regional programmes that consider transboundary risks. Whereas national processes to better understand and monitor risk are underway (in Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen, for example), the lack of information at regional level affects regional capacity for early warning on trans-boundary risks, particularly for multiple hazards. Regional access to national hazard analysis and loss databases has also been identified as a constraint for regional progress. The League of Arab States initiated the first review of progress on the current status of implementing disaster risk reduction in the Arab region in 2007. After encountering significant constraints in the start-up phase, the League has since seen a surge in member countries’ interest in engaging in national as well as regional reporting and coordination (Box 4.11). Box 4.11 Regional progress on early warning for transboundary risks

While the Arab States reported limited progress in addressing trans-boundary risks from a multi-hazard

perspective, some initiatives promise success in years to come. A number of specialized agencies of

the League of Arab States have, in cooperation with their national and regional counterparts, developed

sub-regional early warning systems for specific hazards such as drought and earthquakes. As drought risk is significant in the region, the Arab Centre for the Study of Arid Zones and Dry Lands is establishing regional drought monitoring and warning systems and a Desertification Monitoring and Assessment Network (ADMAnet). Similarly, the Arab Organization for Agricultural Development has established early warning systems for insect infestation (particularly locusts) and for monitoring desertification, drought and floods. The Arab Disaster Risk Reduction Network supports these efforts by facilitating cooperation and coordination of disaster risk management across the region and providing a platform for sharing technologies and lessons learned. Capacity building initiatives such as the Regional Centre for Disaster Risk Reduction – Training and Research, established in 2009, round out a list of significant efforts made in the region over the last few years. Many of the existing regional frameworks and strategies remain skewed towards disaster management and HFA Priority Area 5 (strengthening disaster preparedness). The European Commission, for example, admits that its contributions have to date been mostly to HFA Priority Area 5, but points to a number of ‘projects fitting into a more holistic DRR approach.’ Similarly, the SAARC report emphasizes achievements in response preparedness, particularly when it comes to capacity building. Regional inter-governmental organizations also find it difficult to meaningfully engage non-governmental actors in their processes. For example, SAARC reported that efforts to reach out to a wider audience and involve NGOs and independent experts are regularly limited by the Association’s own ‘rigid rules and procedures’, which can make it impossible to convene multi-stakeholder forums. 4.9 Global gender blindness

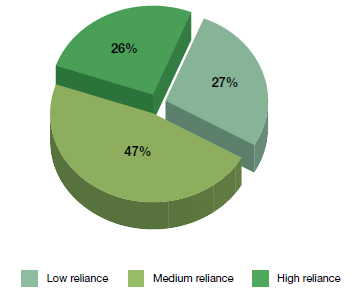

While most countries now have legislation, policies and institutions in place to promote gender equality in employment, health and education, progress on incorporating gender considerations into DRM has been much slower. Figure 4.25

Countries reporting reliance on gender as a cross-cutting issue and driver for risk reduction

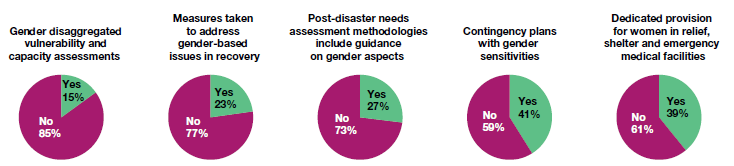

Even countries that score their efforts as ‘significant and ongoing’ such as Brazil and Saint Kitts and Nevis, provided little detail on what constitutes progress or reflects gender across the different priority areas. This limited visibility of the role of gender in DRM is confirmed by the low proportion of countries that included gender considerations in different areas of DRM (Figure 4.26). Few risk assessments consider or generate gender-disaggregated data (see Section 4.2), and few countries incorporate gender-based issues into recovery. Gender-differentiated needs and vulnerabilities remain neglected in recovery assessments with severe consequences for safety and health, particularly of women (Haiti, 2010 Government of Haiti. 2010. Haiti earthquake PDNA: Assessment of damage, losses, general and sectoral needs. Port au Prince, Haiti: Government of Haiti. ;

UNESCAP and UNISDR, 2010. UNESCAP/UNISDR. 2010. Protecting development gains: Reducing disaster vulnerability and building resilience in Asia and the Pacific. The Asia Pacific Disaster Report 2010. Bangkok, Thailand: UNESCAP and UNISDR, ).. Figure 4.26

Countries reporting on progress in gender  These gaps are echoed in country reports. Gender aspects are ‘not taken into account in current risk reduction policies’ in Comoros, and there is no ‘specific policy on gender perspectives in risk reduction’ in Antigua and Barbuda. Argentina, Bolivia, British Virgin Islands, Maldives and Nepal all reported existing gender policies but have difficulty integrating them with DRM. A large number of countries concur with the United Republic of Tanzania, which identifies the lack of appropriate knowledge of ‘how and where to implement gender matters’ as the main barrier. Many countries, including Honduras, reported on gender-based programmes and initiatives led and funded by international organizations, implying that addressing gender considerations remains a donor-driven priority rather than a government one. Although most countries now have legislation, policies and institutions in place to promote gender equality in employment, health and education, progress incorporating gender considerations into DRM is much slower. Some countries, such as Egypt, appear to have difficulty promoting or even protecting the constitutional rights of women in practice. The lack of genderdisaggregated data, as identified by Bahrain, also hampers understanding of how women and men differ in their vulnerability and their specific contributions to reducing disaster risk. As is the case in many countries generally, most of the progress is focused on response and preparedness. This is an obvious and practical area in which to ensure gender equality, but does not necessarily challenge dominant gender dynamics and power relations. Nevertheless, there are exceptions in low- and lower-middleincome countries. In Zambia, for example, assessments conducted for social protection programmes incorporate gender considerations and the different kinds of vulnerabilities of women and children. Despite the hurdles, there are also encouraging and concrete examples of progress. In Ghana, a gender-based NGO was tasked by the national government to engage in a countrywide education campaign for women and humanitarian service providers. The programme included raising women’s awareness of their right to humanitarian support and their role in reducing disaster risk. As a result, women have become more involved in planning and implementing risk reduction activities, particularly in the vulnerable northern regions of the country. Notes 8 A comprehensive questionnaire on all risk drivers

included 24 questions on risk governance and

governability, grouped under four categories: the state

of democracy, government efficiency, the state of law,

and the role of NGOs and international agencies.

Almost 350 informants – from national and local

government, the private sector, NGOs and organized

civil society – responded to the questionnaire.

Respondents were from all seven of the participating

countries, and were all involved in risk management.

Responses were made on a scale of 1 to 9; the lower the

score, the worse the evaluation of existing conditions

and capacities. 9 Civil society responses mirrored a generally negative

view of both state and government efficiency. 10 SOPAC: Pacific Islands Applied Geoscience

Commission; ASEAN: Association of Southeast Asian

Nations; CDEMA: Caribbean Disaster Emergency

Management Agency; CEPREDENAC: Coordinating

Centre for the Prevention of Natural Disasters in

Central America; NEPAD: New Partnership for Africa’s

Development. |

|

x | |

|

|

|

|

||

|