|

Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2011

Revealing Risk, Redefining Development |

|

4.3 Gaps and challenges in early warning systems

Translating warning into concrete

local action is crucial, even in

countries with effective capacities for

forecasting, detecting and monitoring

hazards and suitable technologies for

disseminating advance warnings. In

many countries, even accurate, timely

early warnings were often not acted

upon effectively.

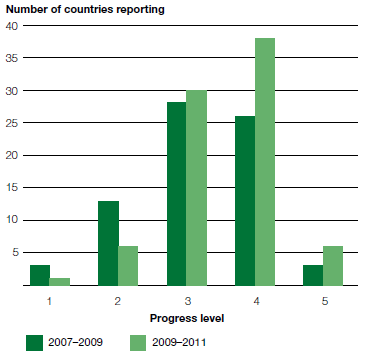

Good overall progress in disaster management is one of the HFA’s major achievements, but challenges remain in the implementation of effective early warning systems. For such systems to be effective, four elements must be in place: accurate hazard warning; an assessment of likely risks and impacts associated with the hazard; a timely and understandable communication of the warning; and the capacity to act on the warning, particularly at the local level. Countries do not report progress on early warning for specific hazards. Results predominantly reflect progress reporting on early warning for fastonset events such as cyclones, certain types of floods and landslides. Overall, half of the countries reported substantial achievements (Figure 4.5), but most of these included limitations in capacities and resources (level 4). A small number reported comprehensive achievement with sustained commitment and capacities at all levels (level 5). Since the last reporting period (2007–2009), progress has been made across all regions and income classes. Significantly, in 2011 only 8 percent of the countries reported minor or some progress (levels 1 and 2), compared with 18 percent in 2009. Figure 4.5

Progress level against core indicators for early warning for both reporting periods

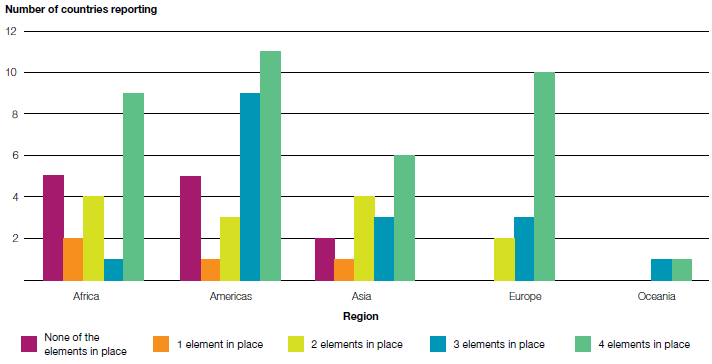

Figure 4.6

Progress reported by countries on key elements of early warning

Many countries reported a need to strengthen national plans, coordination mechanisms and legislation for effective early warning systems, thus echoing the findings of earlier studies (WMO, 2009 WMO (World Meteorological Organization). 2009. Thematic progress review sub-component on early warning systems. Background paper prepared for the 2009 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. ). For example, although authorities may be capable of disseminating early warnings, the warning dissemination chain is often not enforced through policy or legislation. Countries also reported difficulties in coordination, such as a lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities across institutions with responsibility for early warning for different hazards.. Perhaps the key challenge for all countries is translating warning into concrete local action, even for those with effective capacities for forecasting, detecting and monitoring hazards and suitable technologies for disseminating advance warnings. In many countries, even accurate, timely early warnings were often not acted upon effectively. Countries reporting some progress but continued low levels of early warning capacity include Bahrain, Burkina Faso, Lesotho, the Republic of Moldova, Nepal, Sierra Leone, Togo and Yemen. Most of these countries also reported low levels of operational capacity, insufficient coverage of different hazard types, low institutional capacity, lack of resources, and difficulty issuing warnings to the very local level. Conversely, there were also several examples of countries developing innovative ways to communicate warnings to communities. Finland is developing digital radio networks for sharing information and data in emergencies, and also reaches 80 percent of its population with outdoor sirens. Australia and Madagascar are using mobile telephones to communicate warnings. 4.4 Understanding risksCountries from all geographic and income regions reported three main obstacles to undertaking comprehensive risk assessments: limited financial resources; lack of technical capacity; and a lack of harmonization among the instruments, tools and institutions involved. Most countries also reported limited availability of data on localized losses, and difficulties connecting local disaster impact assessments with national monitoring systems and loss databases.Disaster loss data is a prerequisite for understanding risk. Unless a country systematically records its disaster losses, measures the impacts and assesses its risks, then justifying investments in risk reduction will be difficult. The majority of countries (62 out of 82) did report having mechanisms in place to systematically report disaster loss and impacts. However, the associated challenges indicate that these mechanisms do not generate sufficient data, and suffer from fragmentation and limited accessibility. Where data-sharing protocols and mechanisms still do not exist, information remains scattered across various departments within the sector and does not provide a complete picture of national losses. Producing reliable loss and impact information remains a challenge, especially after large disasters or in difficult environments, such as those encountered in Haiti and Myanmar. Moreover, this problem extends to localized losses, where most countries also reported limited data availability and difficulties connecting local disaster impact assessments with national monitoring systems and loss databases. For example, despite confirming that it systematically records disaster losses, Mauritius reported it had no quantitative data on the extent of damages caused by all hazards. Also, as highlighted above, fewer than half of the countries undertook comprehensive multi-hazard risk assessments and less than a quarter did so in any sort of standardized way. Many high-risk countries, such as Armenia, Colombia, Comoros, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Turkey and Viet Nam, reported little progress on multi-hazard risk assessment and identification. There are two reasons for this: in some of these countries such initiatives may have just begun; in others, such as Turkey and Colombia, it more likely reflects a growing and sophisticated understanding of the complexity of the challenge. The European Commission has recognized this complexity and has developed and adopted guidelines for mapping and assessing risk, based on a multi-hazard and multi-risk approach. Canada is currently developing an all-hazards risk assessment framework that will become part of the country’s emergency planning system. Romania has plans for an East European Multi-Risk Management Centre. A number of countries also made efforts to integrate risk assessments into a range of sectors, including health, education, agriculture, transport and water management. Countries from all geographic and income regions reported three main obstacles to undertaking comprehensive risk assessments: limited financial resources; lack of technical capacity; and a lack of harmonization among the instruments, tools and institutions involved. These challenges were also reported by regional and sub-regional intergovernmental organizations. In many countries a wide range of institutions are engaged in institute- and sector-specific assessments. Data on individual hazards and vulnerabilities are scattered across many organizations. This creates problems for the coordination and compatibility of data, and the harmonization of data collection and storage. Encouragingly, some countries are starting to overcome this fragmentation by finding new ways to organize (see, for example, the case of Barbados in Box 4.4). In general, the practice of systematically incorporating risk assessments into recovery programmes has failed to take root overall, with only limited progress since the last reporting period. Most advances have occurred in lowincome countries, where 42 percent report substantial progress (level 4 or 5) in 2011, compared with 29 percent in 2009. Box 4.4 Risk assessments in Barbados

While Barbados admits that risk assessments are not used for development planning, the country notes that comprehensive risk assessments for critical infrastructure and particularly vulnerable areas can be undertaken by coordinating different institutions that are not directly responsible for DRM. Barbados’ Town and Country Planning Department and Coastal Zone Management Unit have jointly developed coastal regulations based on a 100-year storm surge inundation line. Coastal setbacks (buffer zones above a high-water mark) are measured based on distance from this benchmark. The government has committed significant resources (US$30 million) to conduct a comprehensive coastal risk assessment for the major coastal hazards identified. Despite this progress, resources are limited for similar exercises in non-coastal areas of the country. To overcome this barrier, different government departments are acting as lead institutions on other hazards. Specific assessments and hazard maps were developed for an area of Barbados that is particularly vulnerable to landslides and soil erosion, and the existing Soil Conservation Act is used as the driving force for implementing structural and non-structural disaster-mitigation efforts in the area through the country’s Soil Conservation Unit. These measures include the relocation of communities in landslide- and flood-prone areas Where responsibility for risk assessment has been decentralized, countries reported an uneven level of progress depending on technical capacities and resources. Some provinces and districts regularly update comprehensive assessments, while others had difficulty assessing even individual hazards. China provides one such example, reporting substantial progress against this indicator with successful disaster loss and hazard monitoring at national, provincial and city levels. At the same time, it had significant trouble setting up similar systems at the county level. 4.5 From words to investment

Most countries across all geographical and income regions reported relatively little progress toward dedicating resources to strengthening their risk governance capacities. Resources allocated for DRM in individual sectors or for local governments are even more limited.

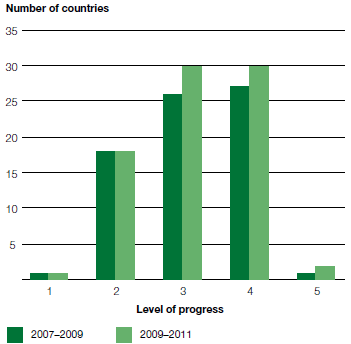

Unsurprisingly, given their difficulty in assessing risks and accounting for losses, countries have difficulty justifying investments in DRM. GAR09 showed that low- and middle-income countries require several hundred billion dollars of development investment per year to upgrade informal human settlements, to restore damaged ecosystems and to provide basic needs. Furthermore, they require specific resources to strengthen risk governance capacities and thus ensure that such investment does indeed reduce risks. The assignment of dedicated resources for this purpose provides a clear indication that countries are really following through on their stated political commitment to the HFA. In 2009–2011, many countries recognized that development investments in poverty reduction, food security and public health reduce risks. However, they find it difficult to quantify these investments, which are provided through diverse instruments including sector budgeting, environmental protection funds, social solidarity and development funds, compensation funds, civil society and, in some countries (Algeria, for example), the private sector. Figure 4.7

Progress in ensuring dedicated and available resources for disaster risk reduction

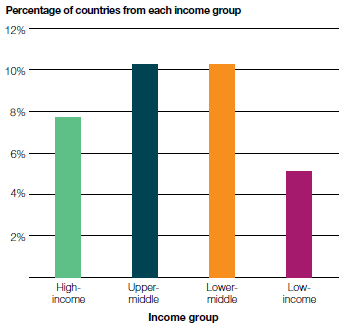

Less than one country in five could describe the percentage of their national budgets assigned to DRM, indicating that allocating dedicated resources remains the exception and not the norm. The figures provided vary from 0.005 percent (Lesotho) to 2.58 percent (Sri Lanka). Even countries such as Viet Nam (Box 4.5) and India, which have both passed legislation to allocate financial resources, found it difficult to quantify their investments. Figure 4.8

Countries reporting on budget allocations to local governments for DRM

Figure 4.9

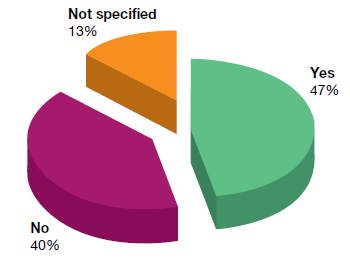

Countries reporting on budget allocations for disaster risk reduction in recovery

While global targets for DRM investment have been suggested – for example, 10 percent of response funds, 2 percent of development funds and 2 percent of recovery funds7 – financial reporting systems still do not allow progress to be monitored against these targets. Figure 4.9 shows that less than half the countries (38 out of 82) budgeted explicitly for DRM within post-disaster recovery programmes and, of these, very few could report specific amounts or percentages of recovery and reconstruction funds assigned to risk reduction. Note 7 10 percent of response suggested by the Under-

Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs at the

Kobe HFA conference, January 2005; and 2 percent of

development and recovery noted in the proceedings of

the Asia Regional Ministerial Conference, 2009.

|

|

x | |

|

|

|

|

||

|