Intensive and extensive risk

Extensive risk is used to describe the risk associated with low-severity, high-frequency events, mainly but not exclusively associated with highly localized hazards. Intensive risk is used to describe the risk associated to high-severity, mid to low-frequency events, mainly associated with major hazards.

UNISDR Global Assessment Report 2015

What is intensive risk?

Intensive disaster risk refers to the risk associated with high-severity, mid to low-frequency disasters. A major hazard can be thought of as a global or regionally large event such as earthquakes, tsunamis, large volcanic eruptions, flooding in large river basins or tropical cyclones.

Intensive risk is comprised of the exposure of large concentrations of people and economic activities to intense hazard events, which can lead to potentially catastrophic disaster impacts involving high mortality and asset loss. Although much as been done to reduce the mortality to some major hazards (e.g. tropical cyclones), intensive risk is growing owing to the increasing concentration of vulnerable people and assets in major hazard areas. For particularly extreme events, for instance in the case of tsunamis, the degree of disaster risk is conditioned more by exposure than by vulnerability. Intensive risk is therefore not only characterized by intense hazards, but also by the underlying risk drivers or vulnerability factors such as poverty and inequality.

What is extensive risk?

Extensive risk refers to the risk associated with low severity, high-frequency (persistent) events, mainly but not exclusively associated with highly localized hazards, including flash floods, storms, fires and agricultural and water-related drought. As such, extensive risk is normally associated with weather-related hazards; however, they can be associated with other hazards, for instance the persistent impact of volcanic ash on the island of Montserrat since 1995 (see Sword-Daniels, 2011). These small but frequent disasters occur in both urban and rural settings, particularly in low and middle-income countries.

Unlike intensive risk, extensive risk is less closely associated with earthquake fault lines and cyclone tracks and more so with underlying risk drivers, such as inequality and poverty, which drive the hazard, exposure and vulnerability.https://www.youtube.com/embed/NcrMzEjM7Qg

Why does extensive risk matter?

Although the impact of intense (or large) events can be severe and losses high, increasing evidence suggests that the accumulated losses from small and recurrent events are significant. Although losses from small and recurrent events is estimated to cause only 14% of total mortality, it is responsible for 42% or more of total economic losses in low and middle-income countries. Extensive risk is also associated with a far greater significant proportion of morbidity and displacement, both of which feed directly into poverty. Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that mortality and economic losses associated with extensive risk are trending upward in low and middle-income countries.

Reports show that the majority of damage and losses since 1990 have been associated with extensive disasters in those countries with consistent data sets. For instance, an analysis across 65 countries and states show that extensive events account for over 90% of interruptions in power and water supply.

Latin America

In a study in Colombia, DesInventar-based data was compared with data for major disasters. Comparing major disasters and small-scale events over the same period shows that while catastrophic events (e.g., earthquakes) result in very high death toll, the human cost of accumulated events, especially affected population, during the same period is significantly high. Further, the accumulated economic cost of small-scale events was found to be higher than the cost of mega disasters.

In the city of Bogotá, rains-induced physical damage and interruption to essential systems (drinking water and sanitation, electricity, gas and telecommunications) occur more frequently than events of natural origin such as floods, torrential rains or earthquakes.

According to data gathered through DesInventar over 16 years (2002-2017), such interruptions average over 1,100 per month and constitute 60% of the total records for this period. The damage to these essential systems increased by half during the latter seven years (2011-2017) as compared to the nine previous years (2002-2010). Further, the greatest relative recurrence (number of interruptions per ten thousand inhabitants) is concentrated in localized areas within the historic city center and other older parts of the city. This may be an indication of the lack of modernization in the older districts of the city that have suffered greater population influx and deterioration due to lack of maintenance.

The invisible toll of disasters

The estimated insured losses from disasters are a staggering US $120 billion — but they represent just the tip of the iceberg. Visit this page to know more.

Africa

Extensive risk can be a particular burden for the low-income households, communities, small businesses and national governments, thus inhibiting economic growth and increasing poverty and undermining development outcomes. The losses from small and recurrent events are not covered by insurance and yet they can amount to more than 10% or more of annual capital formation and indirect losses are rarely accounted for.

In several African cities, seasonal water-logging due to rains has emerged as a major issue. Examples have been found in the informal settlements of Dakar (Senegal), Nairobi (Kenya), Abidjan (Cote d'Ivoire), Monrovia (Liberia), Accra (Ghana), Niamey (Niger), Dar-es-Salam (Tanzania) and Maputo (Mozambique). The flooding of settlements is largely on account of poor drainage, waste management and land-use planning.

The cumulative impact of these low-scale seasonal events, year-after-year, includes deteriorated and abandoned dwellings, contamination of water and indirect impact on informal livelihoods. High incidence of disease (diarrhea and malaria) during the season is common resulting in substantial increase in medical expenses

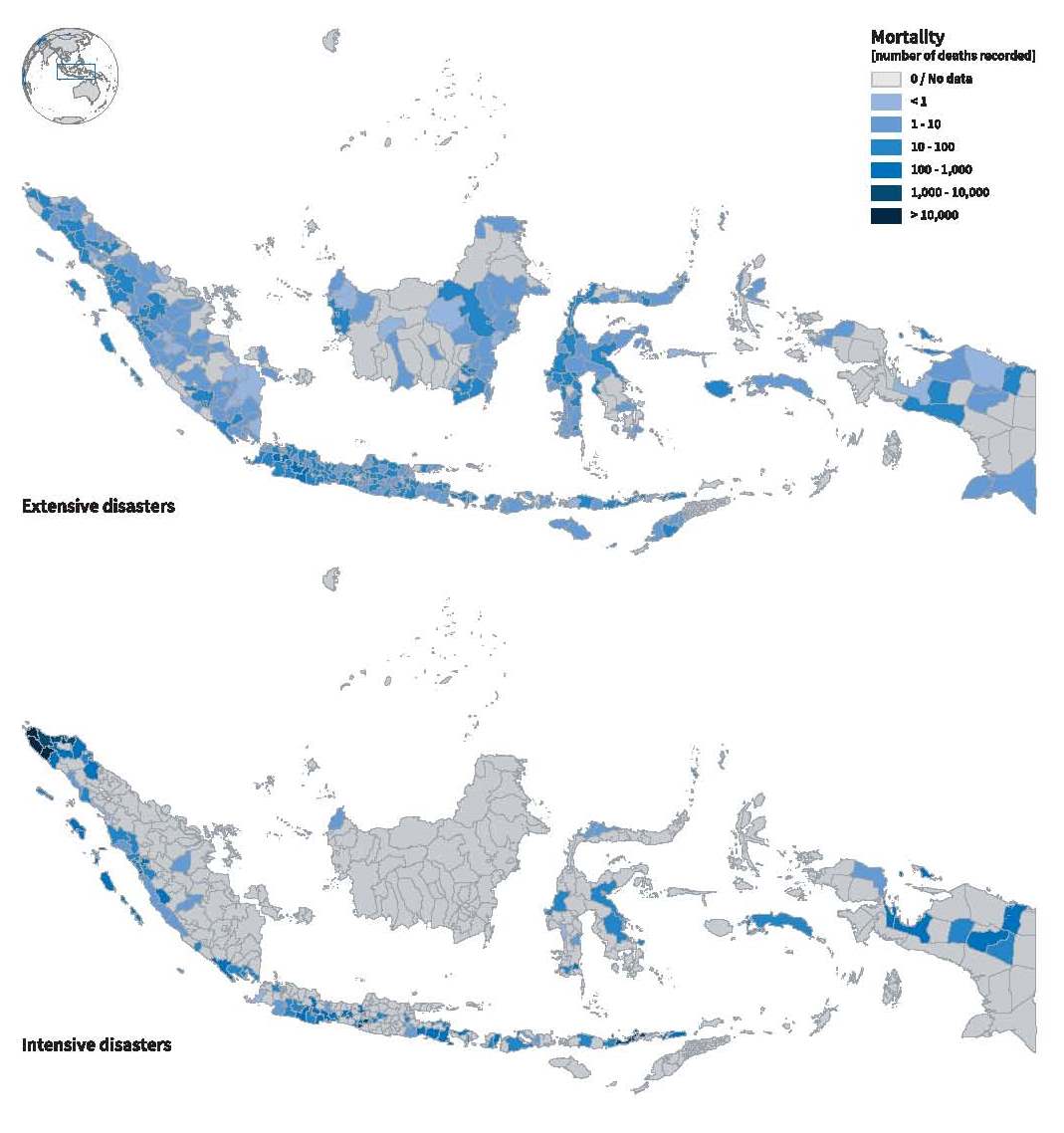

The different footprints of extensive vs intensive disaster loss in Indonesia, 1990-2013

© UNISDR with data from Indonesian national loss database (UNISDR, 2015a)

The examples below show that the accumulated mortality impact of extensive risk events is very high:

Flood

An analysis, conducted for world’s leading 30 countries with large flood-induced mortality over 40 years (1976-2016), showed that the average per-event deaths of small-scale extensive events (40 persons) was only 0.65% of that of the intensive events (6,200 persons). Still, the extensive events accounted for about 70% of the total deaths caused by floods.

Lightning

Data on lightning is sparse and not regularly accounted in disaster losses. Further, given the nature of the hazard, a single event may not cause high mortality and hence often not recorded in all international databases. However, the accumulated impact is high: ranging from 8,862 deaths in India (50 years’ data from 1970-2019) or 1,333 during April-July 2019, to 175 deaths in Myanmar (2014-2017) and at least 23 deaths in Rwanda in 2016.

How do we measure intensive and extensive risk?

In order to measure risk we need to know the location, likelihood, characteristics and intensity of a hazard(s), the number of people and buildings exposed and the social and physical (structural) vulnerability of these people and buildings respectively.

Losses from intense events are usually assessed and reported. In contrast, the cost of losses from small and recurrent events is usually not accounted for. These losses are absorbed by the people affected, attributing to poverty in the process. Unless a country can calculate the cost of these losses, it is unlikely to be able to justify significant investments in disaster risk management in the national budget.

There is no agreed measured distinction between intensive and extensive risk and any quantified threshold between these is arbitrary. However, national loss databases tend not to account for extensive risks. Analysis of 85 countries and two Indian states for the 2015 Global Assessment Report has used a guiding threshold for distinguishing between extensive and intensive risk (see table). By using this threshold, governments have accounted for the frequent disasters associated with extensive risks as well as the infrequent, high-impact intensive risks. Furthermore, because events associated with extensive risk are more frequent than those associated with intensive risk, the analysis of historical loss data is a valid approach to modelling patterns and trends. In contrast, we must rely on computer generated loss data in order to better understand intensive risk because most of the disasters associated with this risk have not yet happened.

| Extensive Risk | Intensive Risk | |

|---|---|---|

| Disaster deaths (mortality) | Less than 30 people killed | 30+ people killed |

| Damage to housing | Less than 600 houses destroyed | 600+ houses destroyed |

Determining the losses from frequent and infrequent events informs measures and activities for reducing, planning for and managing disaster risks. However, measuring losses alone are insufficient for reducing risk - we must also identify and address the factors that make people vulnerable and exposed to certain hazards in the first instance.

How do we reduce intensive and extensive risk?

By understanding and measuring ranges of risk, we can select appropriate risk reduction strategies to address exposure and vulnerability, and when possible, hazard. For instance, the risk associated with low intensity tropical cyclones is largely explained by vulnerability, whereas the risk associated with high intensity cyclones is heavily influenced by exposure. When it is not possible to avoid exposure to events, land use planning and location decisions must be accompanied by other structural or non-structural methods for preventing or mitigating risk.

Unlike intensive risk, extensive risk is less closely associated with earthquake fault lines and cyclone tracks than with inequality and poverty.

UNDRR, 2015a

In many cases, the hazard, exposure and vulnerability are simultaneously constructed by the underlying risk drivers. For example, all of Panama’s municipal areas report extensive disaster losses even though the country lies south of the Caribbean hurricane belt and earthquakes are infrequent.

There are different underlying risk drivers that characterize risk, some of them are:

- Badly planned and managed urban development

- Environmental degradation and ecosystem decline

- Poverty and inequality

- Vulnerable rural livelihoods

- Climate change

- Weak governance

But precisely because risk is constructed through development-related drivers, it is both manageable and avoidable with appropriate investments in disaster risk reduction.

Although exposure increases over time, evidence suggests that wealthier, better-governed cities are better able to reduce their risk. It has been observed that by reducing risk, the potential losses of both frequent and infrequent events are reduced. Most high-income countries have made the regulatory quality and have made investments to significantly reduce the more extensive layers of disaster risk associated with losses over short return periods. In contrast, mortality and economic losses associated with extensive risk appear to be trending upwards in low and middle-income countries. In addition, the citizens of these countries enjoy high levels of social protection, including effective emergency services and health coverage, meaning that high-income countries account for less than 12% of internationally reported disaster mortality.

However, although investments in risk reduction and regulation have enabled a reduction of extensive risk, the value of assets in hazardprone areas has grown, generating an increase in intensive risk. For example, investing in risk reduction measures to protect a floodplain against a 1-in-20-year flood may encourage additional development on the floodplain in a way that actually increases the risks associated with a 1-in-200-year flood.

Intensive and extensive risk are reflected in the cost of different risk financing strategies. It is usually more cost effective for a governments to retain and reduce its more extensive risk than to insure against it. But it is normally more cost effective for a country to insure the more intensive and catastrophic risk – at least up to a certain limit – than to invest in reducing it. However recent disasters such as the Christchurch (New Zealand) earthquakes and Thailand flooding have forced the insurance market to reconsider how to price intensive risks. Beyond the limit of insurance, risks can only be transferred to capital markets or retained. This means that while insurance or other risk transfer options need to be part of a governments risk management strategy, they are only ever part of the solution. Governments need to invest in measures to reduce a considerable proportion of their average annual loss.

Related stories

Scientists warn: Humanity does not have effective tools to resist the tsunami

"An international team of scientists from 20 countries identified 47 problems that hinder the successful prevention and elimination of the consequences of the tsunami."

USA: Human-sparked fires smaller, less intense, but more frequent with longer seasons

"Fires sparked by people steadily increase across US, making fires more frequent over longer seasons, although smaller and less hot than those started by lightening."

‘Flash droughts’ can dry out soil in weeks. New research shows what they look like in Australia

"Droughts can occur simultaneously and may evolve from one type to another. They can last from months to decades, and can cover areas from a region to most of a continent."