Climate change drives disaster risk

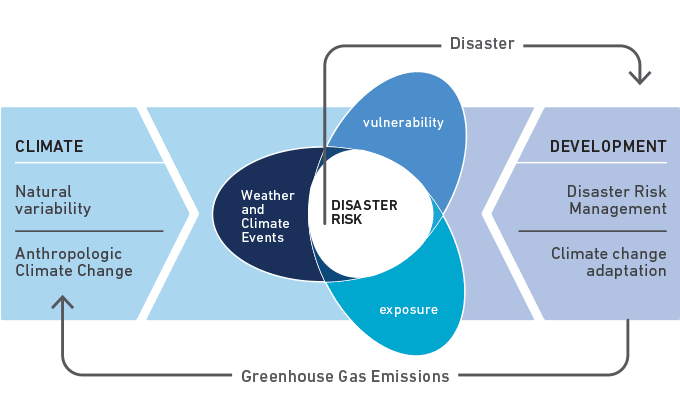

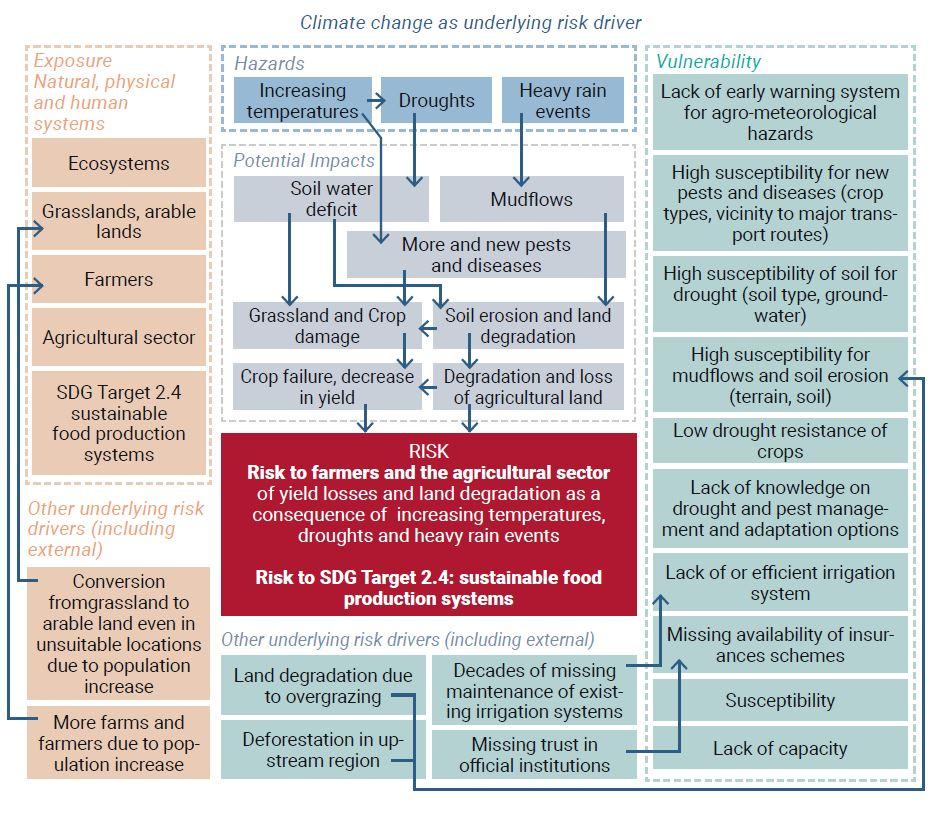

Climate change can increase disaster risk in a variety of ways - by altering the frequency and intensity of hazard events, affecting vulnerability to hazards, and changing exposure patterns.

Disaster risk is magnified by climate change; it can increase the hazard while at the same time decreasing the resilience of households and communities.

Climate change refers to a change in the climate that persists for decades or longer, arising from either natural causes or human activity. Climate change is already modifying the frequency and intensity of many weather-related hazards as well as steadily increasing the vulnerability and eroding the resilience of exposed populations that depend arable land, access to water, and stable mean temperatures and rainfall. Climate change could also lead to changes in the geographic distribution of weather-related hazards, which may lead to new patterns of risk.

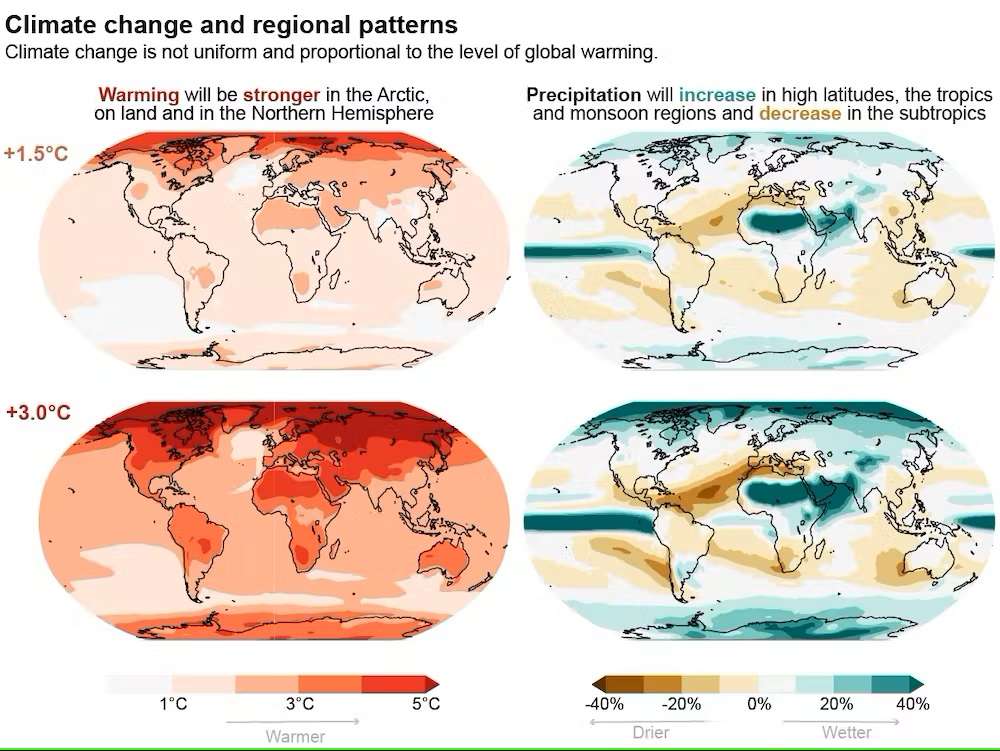

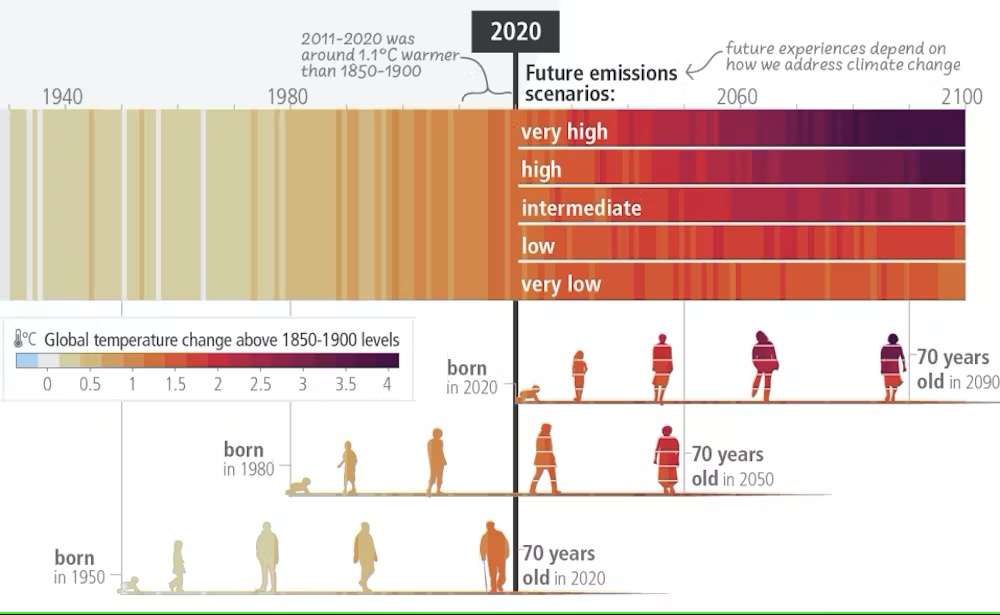

According to a new update issued by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) global temperatures are likely to surge to record levels in the next five years, fuelled by heat-trapping greenhouse gases and a naturally occurring El Niño event. There is a 66% likelihood that the annual average near-surface global temperature between 2023 and 2027 will be more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels for at least one year. There is a 98% likelihood that at least one of the next five years, and the five-year period as a whole, will be the warmest on record. In addition, predicted precipitation patterns for the May to September 2023-2027 average, compared to the 1991-2020 average, suggest increased rainfall in the Sahel, northern Europe, Alaska and northern Siberia, and reduced rainfall for this season over the Amazon and parts of Australia.

Farmers in Ghana can’t predict rainfall anymore, changing how they work

Farmers, in Ghana, have indicated that 30 years ago, the rains were constant during specific months of the year. This enabled them to plan and organise themselves for their yearly farming activities, as they were able to predict rains and start of the farming season. But rainfall patterns have become very variable.

A consequence of this was that farmers could no longer exchange labour in a system known as Nnoboa. This is often based on the principle of helping one another on the farm as a way of building social bonds. But the variable nature of the rains had distorted the farming seasons and organisation of Nnoboa - communal labour. Instead farmers were relying on their nuclear families or hired labour. This reflected a much more individualist – as opposed to a communal – approach to farming.

Although the precise impact of climate change is not certain, and it is important to be aware that not all areas will be impacted in the same way, projected impacts of climate change that will drive disaster risk include:

- Droughts: The number of people suffering extreme droughts across the world could double in less than 80 years, which has major implications for the livelihoods of the rural poor, and can also lead to increased migration streams. There will likely be a large reduction in natural land water storage in two-thirds of the world, especially in the Southern Hemisphere.

- Sea level rise: Coastal flooding events could threaten assets worth up to 20 % of the global GDP by 2100. The population of coastal areas has grown faster than the overall increase in global population. Global “hotsports” for flooding are projected to be in north western Europe and Asia.

- Infectious diseases: By 2050, mosquitoes that carry vectore-borne diseases like Malaria could reach an estimated 500 million people. Global warming has led to a loss in biodiversity, resulting in increased transmission and incidence of disease. Due to altered climate patterns, urbanization and deforestation bats and rodents, which are responsible for 60 percent of the diseases transmitted from animals to humans, have flourished.

- Wildfires: By 2030, fire season could be three months longer in areas already exposed to wildfires. In Western Australia, for example, this would add up to three months of days with high wildfire potential.

- Cyclones: Even though the attribution of tropical cyclones to climate change is difficult, a robust increase of the most devastating storms with climate change is evident. Under 2.5°C of global warming, the most devastating storms are projected to occur up to twice as often as today.

In the new IPCC report, released March 20, 2023, the IPCC summarizes the findings from a series of assessments written over the past eight years. Here are two essential reads by co-authors of some of those reports:

- More intense storms and flooding: The IPCC warns in the sixth assessment report that the water cycle will continue to intensify as the planet warms. That includes extreme monsoon rainfall, but also increasing drought, greater melting of mountain glaciers, decreasing snow cover and earlier snowmelt.Annual average precipitation is projected to increase in many areas as the planet warms, particularly in the higher latitudes.IPCC sixth assessment report

- The longer the delay, the higher the cost: The longer countries wait to respond, the greater the damage and cost to contain it. One estimate from Columbia University put the cost of adaptation needed just for urban areas at between US$64 billion and $80 billion a year – and the cost of doing nothing at 10 times that level by mid-century.

Risk associated with weather-related hazards is disproportionately concentrated in developing countries and within these countries in poorer sectors of the population. Poverty and constrained access to productive assets mean that rural livelihoods that depend on agriculture and other natural resources are vulnerable to even slight variations in weather and seasonality.

The impact of climate change in rural and urban areas is intimately linked. As the sustainability of rural livelihoods declines and disaster risk increases, it is possible that increased rural to urban migration may occur. Related to climate change, in rural areas more frequent and extreme droughts, as well as changes in mean temperature and precipitation levels will cause further stress to these already vulnerable livelihoods.

“An intensifying water cycle means that both wet and dry extremes and the general variability of the water cycle will increase, although not uniformly around the globe."

Matthew Barlow

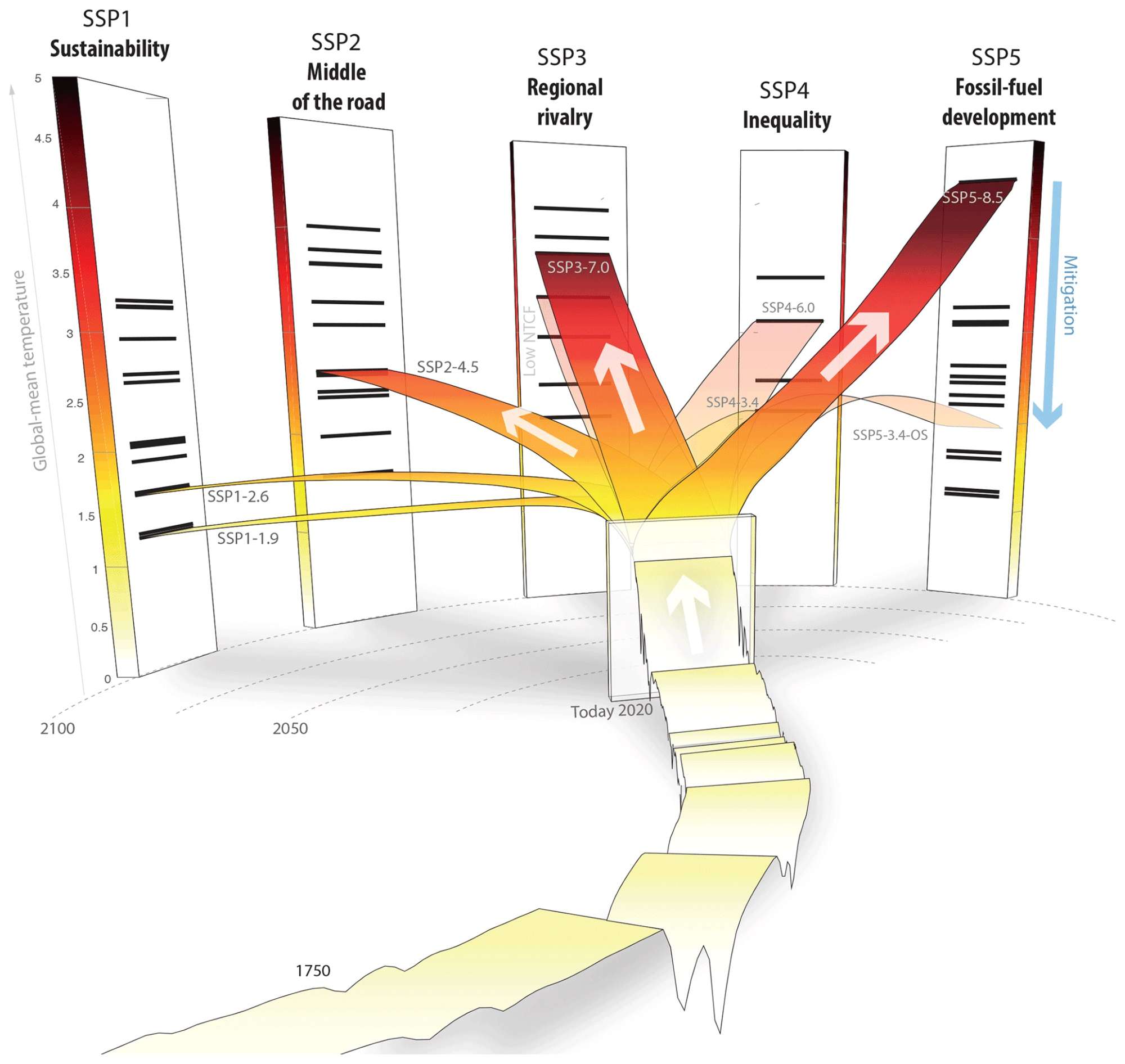

Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP)

The SSPs are part of a new scenario framework, established by the climate change research community in order to facilitate the integrated analysis of future climate impacts, vulnerabilities, adaptation, and mitigation. The pathways were developed over the last years as a joint community effort and describe plausible major global developments that together would lead in the future to different challenges for mitigation and adaptation to climate change. The SSPs are based on five narratives describing alternative socio-economic developments, including sustainable development, regional rivalry, inequality, fossil-fueled development, and middle-of-the-road development. The narrative for each is described in detail below:

| SSP1 | Sustainability – Taking the Green Road (Low challenges to mitigation and adaptation) The world shifts gradually, but pervasively, toward a more sustainable path, emphasizing more inclusive development that respects perceived environmental boundaries. Management of the global commons slowly improves, educational and health investments accelerate the demographic transition, and the emphasis on economic growth shifts toward a broader emphasis on human well-being. Driven by an increasing commitment to achieving development goals, inequality is reduced both across and within countries. Consumption is oriented toward low material growth and lower resource and energy intensity. |

| SSP2 | Middle of the Road (Medium challenges to mitigation and adaptation) The world follows a path in which social, economic, and technological trends do not shift markedly from historical patterns. Development and income growth proceeds unevenly, with some countries making relatively good progress while others fall short of expectations. Global and national institutions work toward but make slow progress in achieving sustainable development goals. Environmental systems experience degradation, although there are some improvements and overall the intensity of resource and energy use declines. Global population growth is moderate and levels off in the second half of the century. Income inequality persists or improves only slowly and challenges to reducing vulnerability to societal and environmental changes remain. |

| SSP3 | Regional Rivalry – A Rocky Road (High challenges to mitigation and adaptation) A resurgent nationalism, concerns about competitiveness and security, and regional conflicts push countries to increasingly focus on domestic or, at most, regional issues. Policies shift over time to become increasingly oriented toward national and regional security issues. Countries focus on achieving energy and food security goals within their own regions at the expense of broader-based development. Investments in education and technological development decline. Economic development is slow, consumption is material-intensive, and inequalities persist or worsen over time. Population growth is low in industrialized and high in developing countries. A low international priority for addressing environmental concerns leads to strong environmental degradation in some regions. |

| SSP4 | Inequality – A Road Divided (Low challenges to mitigation, high challenges to adaptation) Highly unequal investments in human capital, combined with increasing disparities in economic opportunity and political power, lead to increasing inequalities and stratification both across and within countries. Over time, a gap widens between an internationally-connected society that contributes to knowledge- and capital-intensive sectors of the global economy, and a fragmented collection of lower-income, poorly educated societies that work in a labor intensive, low-tech economy. Social cohesion degrades and conflict and unrest become increasingly common. Technology development is high in the high-tech economy and sectors. The globally connected energy sector diversifies, with investments in both carbon-intensive fuels like coal and unconventional oil, but also low-carbon energy sources. Environmental policies focus on local issues around middle and high income areas. |

| SSP5 | Fossil-fueled Development – Taking the Highway (High challenges to mitigation, low challenges to adaptation) This world places increasing faith in competitive markets, innovation and participatory societies to produce rapid technological progress and development of human capital as the path to sustainable development. Global markets are increasingly integrated. There are also strong investments in health, education, and institutions to enhance human and social capital. At the same time, the push for economic and social development is coupled with the exploitation of abundant fossil fuel resources and the adoption of resource and energy intensive lifestyles around the world. All these factors lead to rapid growth of the global economy, while global population peaks and declines in the 21st century. Local environmental problems like air pollution are successfully managed. There is faith in the ability to effectively manage social and ecological systems, including by geo-engineering if necessary. |

Attribution science

What is attribution science?

Attribution science is a field of climate science that investigates the links between climate change and extreme weather events. This new but rapidly growing field of research aims to estimate how human-induced climate change affects the magnitude and probability of an event. Attribution science cannot determine if climate change caused an event. But it can determine if climate change made some extreme events more severe and more likely to occur, and if so, by how much.

See more resources here.

Opportunities for building resilience

It is important to differentiate between climate change and the disaster risks associated with climate change. However, as with all the underlying risk drivers, because climate change is so closely linked to a number of other risk drivers, it must be addressed in combination with reducing these other drivers of risk. If these drivers are not addressed, disaster risk will continue to increase even if climate change is successfully mitigated.

Patterns of risk that may be driven by climate change are also related to factors such as the growth of informal settlements in exposed areas, lack of investment in drainage infrastructure, and deficiencies in urban and local governance. By addressing these, we can build resilience to climate change.

Climate change has emerged as a sector in itself at the national, regional and international levels, with its own institutional arrangements, global framework, and funding mechanisms. Since the formulation of the Nairobi Work Programme at the Conference of the Parties in 2006, a plethora of strategies, frameworks and funding mechanisms has certainly created the impression of convergence and coherence of climate change agendas with those of disaster risk reduction and sustainable development.

It is not inevitable that climate change leads to increasing disaster risk.

Addressing the underlying risk drivers is key to both disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation.

UNDRR, 2009b

Several countries, such as the Philippines, Vietnam and others in the Pacific region, have managed to take the opportunity to effectively merge regulation and technical guidelines as well as national policy frameworks and budgets for disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation. However, those countries remain the minority, and most national policies, despite citing the respective other domain, maintain distinct boundaries in concepts, plans, methodologies, reporting lines, responsibilities, budgets, and other areas.

How Kiribati is shoring up food security and community resilience in the face of global climate change

In Kitibati, King tides, a natural part of the tidal cycle, are becoming more prolonged and more frequent, contaminating water, destroying crops, and damaging infrastructure such as roads. In February 2015, a particularly high tide destroyed the hospital’s maternity ward, toilet block, and part of the sea wall built to protect it.

The Government of Kiribati has developed and is now implementing a comprehensive 9-year plan for advancing climate change adaptation and reducing disaster risk. The plan, closely aligned with the national vision for sustainable development, identifies increasing water and food security, including promoting healthy and resilient ecosystems, as one of the plan’s 12 key strategies.

Related Sections on Preventionweb

Is this page useful?

Yes No Report an issue on this pageThank you. If you have 2 minutes, we would benefit from additional feedback (link opens in a new window).