|

Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2011

Revealing Risk, Redefining Development |

|

7.3 Decentralization of DRM functions

Effective local action requires human

capacity, financial resources and

political authority. Central policy

responsibility for disaster risk

reduction must be complemented

by adequately decentralized and

layered risk management functions,

capacities and corresponding

budgets.

Across the world, central governments are quietly sharing more power with subnational actors (O’Neill, 2005). In theory, decentralization facilitates citizen participation, more engaged decision makers, more local knowledge, more resources and more accountability, but in reality, that potential may not be always realized (  Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper.  IFRC, 2011 IFRC, 2011 IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). 2011. Desk review on trends in the promotion of community-based disaster risk reduction through legislation. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). 2011. Desk review on trends in the promotion of community-based disaster risk reduction through legislation. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Pelling, M. 2010. Urban governance and disaster risk reduction in the Caribbean: The experiences of Oxfam GB. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. ; ECHO, 2008. ECHO (European Commission Humanitarian Aid department). 2008. Vulnerabilidades, capacidades y gestión de riesgo en la república del Perú. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission Humanitarian Aid department. ; Salazar, 2010. Salazar, M. 2010. El niño throws a tantrum. Tierramerica. Rome, Italy: Inter Press Service (IPS), 24 February 2010. ;

.  Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. von Hesse, M., Kamiche, J. and de la Torre, C. 2008. Contribución temática de America Latina al informe bienal y evaluación mundial sobre la reducción de riesgo 2009. Contribution to the GTZ-UNDP Background Paper prepared for the 2009 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. ; Hardoy, 2010. Hardoy, J. 2010. Local disaster risk reduction in Latin America urban areas. Case studies developed for the IIED Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. ).

Some 900 of Colombia’s 1,098 municipalities

have mandated local committees for disaster risk

reduction, but only 14 percent implemented

emergency and contingency plans. A similar

story is seen with South Africa’s 2002 Disaster

Management Act. Although DRM is supposed

to be integrated into development planning in

most municipalities (Botha et al. Botha, D., Van Niekerk, D., Wentink, G., Tshona, T., Maartens, Y., Forbes, K., Annandale, E., Coetzee, C. and Raju, E. 2010. Disaster risk management status assessment at municipalities in South Africa. Pretoria: South African Local Government Association (SALGA). Draft report. .. Botha, D., Van Niekerk, D., Wentink, G., Tshona, T., Maartens, Y., Forbes, K., Annandale, E., Coetzee, C. and Raju, E. 2010. Disaster risk management status assessment at municipalities in South Africa. Pretoria: South African Local Government Association (SALGA). Draft report. , 2010), poor

local government capacity has severely limited

integration (.  IFRC, 2011 IFRC, 2011 IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). 2011. Desk review on trends in the promotion of community-based disaster risk reduction through legislation. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). 2011. Desk review on trends in the promotion of community-based disaster risk reduction through legislation. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Johnson, C. 2011. Creating an enabling environment for reducing disaster risk: Recent experience of regulatory frameworks for land, planning and building. Background paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. ; .  Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T. and Davis, I. 2004. At risk: Natural hazards, people's vulnerability and disasters. London, UK: Routledge. ).

Decentralization without supporting legislation

has also proven very challenging in countries

that have attempted it, such as Timor-Leste

(.  IFRC, 2011 IFRC, 2011 IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). 2011. Desk review on trends in the promotion of community-based disaster risk reduction through legislation. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). 2011. Desk review on trends in the promotion of community-based disaster risk reduction through legislation. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Kuntjoro, I. and Jamil, S. 2010. Triple trouble in Indonesia: Strengthening Jakarta’s disaster preparedness. Singapore: Centre for Non-Traditional Security Studies. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), RSIS Commentaries. ). In its self-assessment, India also reported that the devolution of power and financial resources to local authorities has been a major challenge, often hampered by state governments’ retention of control.

More attention, therefore, needs to be paid to how DRM functions are layered and tailored to local contexts. DRM activities need to be locally grounded, and responsibilities should be devolved to the local level as much as capacities allow. Not all functions need to be fully decentralized, however, and some may be more appropriately located at higher levels, with greater capacity, political weight and decision-making power. For example, central governments should provide technical, financial and policy support, and take over responsibility for DRM when local capacities are exceeded (.  Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Box 7.2 An alternative resource mechanism – cities in China sharing human resources, experiences and finances

China has a twinning programme that transfers financial and technical support from one province or municipality to a disaster-affected area with less human and financial resources. The twinning agreement diverts 1 percent of the annual income plus technical capacity from the richer province to fund recovery projects in the poorer province for three years.

After the 2008 earthquake in China, one such programme allowed funds from Shandong Province and Shanghai Municipality to rebuild schools and hospitals in Beichuan County and Dujiangyan City to higher standards. Shandong and Shanghai also deployed staff to the newly rebuilt institutes to provide on-the-job guidance, and they invited teachers, doctors and managers to the donor provinces to receive training. Twinning provides benefits to both recipients and donors, building experience, capacities and government networks within the country or region. It provides a stable source of funding and critical capacity sharing for a number of years, and encourages longer-term partnerships and risk sharing. Twinning also helps with the increased demand for skills after a disaster, as well as building these capacities. It can be agreed on before a disaster, allowing for fast and predictable deployment during recovery. (Source:  Ievers and Bhatia, 2011 Ievers and Bhatia, 2011 Ievers, J. and Bhatia, S. 2011. Recovery as a catalyst for reducing risk. IRP Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Ievers, J. and Bhatia, S. 2011. Recovery as a catalyst for reducing risk. IRP Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Complete decentralization of budgeting and reporting can also generate problems. Although it may ensure that spending is in line with local priorities, it almost inevitably leads to divisions with national and sector policies and programmes (Benson, 2011 Benson, C. 2011. Integrating disaster risk reduction into national development policy and practice. In: The Routledge handbook of hazards and disaster risk reduction and management, J.C. Gaillard, I. Kelman and B. Wisner, eds. London, UK: Routledge. ).. An incremental approach to decentralization (Box 7.3) may be the best alternative. Where local government capacity and resources are particularly weak, ‘deconcentration’ may be a good interim step towards the full devolution of responsibilities and functions. In Mozambique, for example, responsibility for DRM is highly centralized in the National Institute for Disaster Management (INGC). Its functions, however, are implemented through deconcentrated regional offices and local committees, separate from and in parallel to the decentralized system of local administration. As disaster risk reduction has a high profile in Mozambique, these deconcentrated mechanisms are well resourced, and staff can relocate freely between central and local levels depending on needs. Given that local government capacity is weak, most risk reduction functions are undertaken by INGC staff (  Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Box 7.3 Towards more responsible and responsive local risk reduction

An incremental approach to decentralizing disaster risk reduction can address limited local capacities,

a primary barrier to effective local governance. Other options for addressing the problem of low

capacity are:

(Source:  Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. 7.4 Strengthening accountability

Access to information on disaster risk,

particularly for the most vulnerable,

is the first step in reducing disaster

losses. Good risk governance

requires disaster-prone populations to

know their risks as well as their rights,

and a responsive and accountable

civil society engaged in constructive

dialogue with governments.

The quality of national and local governance in general, and factors such as voice and accountability in particular, influence why some countries have far higher disaster mortality and relative economic loss than others (Kahn, 2005 Kahn, M.E. 2005. The death toll from natural disasters: The role of income, geography, and institutions. Review of Economics and Statistics 87 (2): 271–284. ; Stromberg, 2007. Stromberg, D. 2007. Natural disasters, economic development, and humanitarian aid. Journal of Economic Perspectives 21 (3): 199–222. ; UNISDR, 2009.  UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2009. Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction: Risk and poverty in a changing climate. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2009. Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction: Risk and poverty in a changing climate. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction.Click here to go to GAR09 page. Lavell, C., Canteli, C., Rudiger, J. and Ruegenberg, D. 2010. Data spread sheets developed in support of the DARA 'risk reduction index: Conditions and capacities for risk reduction'. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. ). Corruption also affects the level

of trust that citizens have in their government,

administration and services (Rose-Ackerman, 2001. Rose-Ackerman, S. 2001. Trust, honesty, and corruption: Reflection on the state-building process. Public Policy Working Papers No. 255. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard Law School, and John M. Olin Center for Studies in Law, Economics. ; Morris and Klesner, 2010. Morris, S. and Klesner, J. 2010. Corruption and trust: Theoretical considerations and evidence from Mexico. Comparative Political Studies 43 (10): 1258–1285. ). In general,

more democratic, accountable states with more effective institutions tend to suffer lower

mortality (Anbarci et al., 2005. Anbarci, N., Escaleras, M. and Register, C.A. 2005. Earthquake fatalities: The interaction of nature and political economy. Journal of Public Economics 89 (9–10): 1907–1933. ; Escaleras et al., 2007. Escaleras, M., Anbarci, N. and Register, C.A. 2007. Public sector corruption and major earthquakes: A potentially deadly interaction. Public Choice 132 (1–2): 209–230. ).. If it is true that ‘political survival lies at the heart of disaster politics’ (Smith and Quiroz Flores, 2010 Smith, A. and Quiroz Flores, A. 2010. Disaster politics: Why earthquakes rock democracies less. Foreign Affairs (15 July 2010). ), then accountability mechanisms are

particularly important in generating political

and economic incentives for disaster risk

reduction. The risk of being held to account

for decisions that result in avoidable disaster

risk can be a powerful incentive to make DRM

work.Available at http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/66494/alastair-smith-and-alejandro-quiroz-flores/disaster-politics. In DRM, as in many development sectors, establishing accountability is not straightforward (  Olson et al., 2011 Olson et al., 2011 Olson, R. Sarmiento Prieto and J. Hoberman, G. 2011. Disaster risk reduction, public accountability, and the role of the media: Concepts, cases and conclusions. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Olson, R. Sarmiento Prieto and J. Hoberman, G. 2011. Disaster risk reduction, public accountability, and the role of the media: Concepts, cases and conclusions. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Nevertheless, there are examples where direct responsibility for action and inaction is monitored, and bearing personal responsibility for disaster losses can provide a powerful incentive for investing in DRM. Indonesia has enacted legislation that makes leaders directly responsible for disaster losses, and in Colombia the decentralization of DRM responsibilities has meant that mayors have been imprisoned when people were found to have died needlessly from a disaster (  Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott and Tarazona, 2011 Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Access to information is a key factor that drives accountability (World Bank, 2010b World Bank. 2010b. Natural hazards, unnatural disasters: The economics of effective prevention. Washington DC, USA: The World Bank and United Nations. ; .  Gupta, 2011 Gupta, 2011 Gupta, M. 2011. Filling the governance ‘gap’ in disaster risk reduction. Background Paper prepared by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN) and for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Gupta, M. 2011. Filling the governance ‘gap’ in disaster risk reduction. Background Paper prepared by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN) and for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper.  Gupta, 2011 Gupta, 2011 Gupta, M. 2011. Filling the governance ‘gap’ in disaster risk reduction. Background Paper prepared by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN) and for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Gupta, M. 2011. Filling the governance ‘gap’ in disaster risk reduction. Background Paper prepared by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN) and for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. The 1883 explosion of Krakatoa, Indonesia, followed the introduction of the telegram, and so became the first globally reported disaster (Winchester, 2003 Winchester, S. 2003. Krakatoa: The day the world exploded: August 27, 1883. New York, USA: HarperCollins. ). Today, most disasters are broadcast around the world in real time, through television, radio, print media, mobile social networking and the Internet. The media, therefore, plays an increasingly important role in holding governments, NGOs, international organizations and other stakeholders to account (.  Olson et al., 2011 Olson et al., 2011 Olson, R. Sarmiento Prieto and J. Hoberman, G. 2011. Disaster risk reduction, public accountability, and the role of the media: Concepts, cases and conclusions. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Olson, R. Sarmiento Prieto and J. Hoberman, G. 2011. Disaster risk reduction, public accountability, and the role of the media: Concepts, cases and conclusions. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Radford, T. and Wisner, B. 2011. Media, communication and disaster. In Handbook of hazards and disaster risk reduction. B. Wisner, J.C. Gaillard and I. Kelman, eds. London, UK: Routledge (in press). ; Wisner et al., 2011. Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T. and Davis, I. 2004. At risk: Natural hazards, people's vulnerability and disasters. London, UK: Routledge. ).. The media play four different roles in the wake of disasters: observing and reporting facts such as mortality rates and the volume of assistance provided, holding governments and humanitarian actors to account, analysing the causes of the disaster and raising public awareness about potential improvements in DRM (  Olson et al., 2011 Olson et al., 2011 Olson, R. Sarmiento Prieto and J. Hoberman, G. 2011. Disaster risk reduction, public accountability, and the role of the media: Concepts, cases and conclusions. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Olson, R. Sarmiento Prieto and J. Hoberman, G. 2011. Disaster risk reduction, public accountability, and the role of the media: Concepts, cases and conclusions. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper.  Olson et al., 2011 Olson et al., 2011 Olson, R. Sarmiento Prieto and J. Hoberman, G. 2011. Disaster risk reduction, public accountability, and the role of the media: Concepts, cases and conclusions. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Olson, R. Sarmiento Prieto and J. Hoberman, G. 2011. Disaster risk reduction, public accountability, and the role of the media: Concepts, cases and conclusions. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

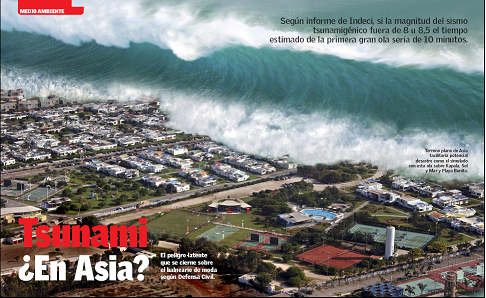

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Box 7.4 The role of the media following the 2010 Haiti and Chile earthquakes Figure 7.1

Excerpt from El Comercio: hypothetical tsunami striking a beach community south of Lima

(Source: El Comercio, 18 February 2010)

(Source:  Olson et al., 2011 Olson et al., 2011 Olson, R. Sarmiento Prieto and J. Hoberman, G. 2011. Disaster risk reduction, public accountability, and the role of the media: Concepts, cases and conclusions. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Olson, R. Sarmiento Prieto and J. Hoberman, G. 2011. Disaster risk reduction, public accountability, and the role of the media: Concepts, cases and conclusions. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Evidence suggests that a culture of social accountability, and specific mechanisms to ensure it, can directly improve the effectiveness of governance and service delivery (  Acharya, 2010 Acharya, 2010 Acharya, B. 2010. Social accountability in DRM – drawing lessons from social audit of MGNREGS. Case study prepared for Acharya, B. 2010. Social accountability in DRM – drawing lessons from social audit of MGNREGS. Case study prepared for  Gupta, 2011 Gupta, 2011 Gupta, M. 2011. Filling the governance ‘gap’ in disaster risk reduction. Background Paper prepared by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN) and for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Gupta, M. 2011. Filling the governance ‘gap’ in disaster risk reduction. Background Paper prepared by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN) and for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Click here to view this GAR paper.  Daikoku, 2010 Daikoku, 2010 Daikoku, L. 2010. Citizens for clean air, New York. Case study prepared for the ADRRN Background Paper to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Daikoku, L. 2010. Citizens for clean air, New York. Case study prepared for the ADRRN Background Paper to the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper.  IFRC, 2011 IFRC, 2011 IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). 2011. Desk review on trends in the promotion of community-based disaster risk reduction through legislation. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). 2011. Desk review on trends in the promotion of community-based disaster risk reduction through legislation. Background Paper prepared for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster

Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Whereas such laws are important, they do not necessarily strengthen actual accountability unless they are supported by penalties and/or effective performance-based rewards. For example, provisions in legislation and the regulation of public office can specify the liabilities of politicians and government leaders, becoming more effective when linked to expenditure and budgets. Transparent contractual arrangements between government departments and between government and private service providers also contribute to increased accountability. Where rights and obligations are clearly articulated and tied to concrete performance measures, service delivery can improve dramatically (Box 7.5). Box 7.5 Social audits to ensure accountability in rural employment in India

India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) facilitates accountability by both

governments and civil society. It includes decentralized planning and implementation, proactive

disclosures and mandatory social audits of all projects. The impetus was provided by strong political

will and a committed high-level bureaucracy. In 2006, the Strategy and Performance Innovation Unit

(SPIU) of the Department of Rural Development, collaborated with MKSS, a civil society organization

in Rajasthan that pioneered social auditing in India, to train officials and civil society activists and to

design and conduct pilot social audits. This process trained 25 civil society resource persons at the

state level, complemented by 660 more at the district level, with audits conducted by educated youth

volunteers identified and trained by this pool of expertise.

Since the first social audit was conducted in July 2006, an average of 54 social audits have been conducted every month across all 13 NREGA districts. Whether audits have resulted in improved accountability in service delivery needs to be researched, but significant and lasting impacts are already evident, including improvements in citizens’ awareness levels, their confidence and self-respect, and importantly, their ability to engage with local officials. (Source:  Acharya, 2010 Acharya, 2010 Acharya, B. 2010. Social accountability in DRM – drawing lessons from social audit of MGNREGS. Case study prepared for Acharya, B. 2010. Social accountability in DRM – drawing lessons from social audit of MGNREGS. Case study prepared for  Gupta, 2011 Gupta, 2011 Gupta, M. 2011. Filling the governance ‘gap’ in disaster risk reduction. Background Paper prepared by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN) and for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR. Gupta, M. 2011. Filling the governance ‘gap’ in disaster risk reduction. Background Paper prepared by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN) and for the 2011 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR.Click here to view this GAR paper. Click here to view this GAR paper. NOTE 1 For more information, refer to www.sc.gov.cn/zt_sczt/zhcjmhxjy/cjjy/kjcj/200912/t20091217_871603.shtml and www.sc.gov.cn/zt_sczt/zhcjmhxjy/dkzy/sf/200912/t20091201_859811.shtml |

|

x | |

|

Archer, D. and Boonyabancha, S. 2010. Seeing a disaster as an opportunity, harnessing the energy of disaster survivors for change. Case study prepared for the IIED Background Paper and GAR11. [View] Daikoku, L. 2010. Citizens for clean air, New York. Case study prepared for the ADRRN. [View] Gupta, M. 2011. Filling the governance ‘gap’ in disaster risk reduction. Paper prepared by the Asian Disaster Reduction and Response Network (ADRRN). [View] Herranz, P. Human rights and accountability. Case study prepared for the ADRRN. [View] Ievers, J. and Bhatia, S. 2011. Recovery as a catalyst for reducing risk. IRP. [View] IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies). 2011. Desk review on trends in the promotion of community-based disaster risk reduction through legislation. [View] Karayalcin, C. and Thompson, P. 2010. Decision-making constraints on the implementation of viable disaster risk reduction projects. Some perspectives from economics. [View] Llosa, S. and Zodrow, I. 2011. Disaster risk reduction legislation as a basis for effective adaptation. [View] Olson, R. Sarmiento Prieto and J. Hoberman, G. 2011. Disaster risk reduction, public accountability, and the role of the media: Concepts, cases and conclusions. . [View] Satterthwaite, D. 2011. What role for low-income communities in urban areas in disaster risk reduction? . [View] Scott, Z. and Tarazona, M. 2011. Decentralization and disaster risk reduction. Study on disaster risk reduction, decentralization and political economy analysis for UNDP contribution to the GAR11. [View] Williams, G. 2011. The political economy of disaster risk reduction. Study on Disaster Risk Reduction, Decentralization and Political Economy Analysis for UNDP contribution to the GAR11. [View] |

|

|

||

|