Unravelling complexity through Impact Webs: a novel approach for mapping the systemic nature of risks

Impacts from natural hazards, climate change and other human-generated shocks do not occur in isolation.

Risks from these types of events – and our responses to them – exhibit complex characteristics that are felt across sectors and national borders. The effects of one impact can trigger another impact, sometimes in a place that is far from the original event (known as cascading effects).

Policy responses to reduce impacts in one location or for one group of people can create undesirable effects that worsen a situation elsewhere, for another group of people. Things don’t necessarily move in a straight line, and cause and effect aren’t always correlated in the way we assume. Many of these effects are non-linear, and go under the radar, remaining hidden until they manifest as impacts. These complex characteristics are what make risks systemic.

Managing the systemic nature of risks

To meet the expected outcome of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction and the Sustainable Development Goals, we must better understand and manage the systemic nature of risks.

Systemic risk can be understood as the spread of possible and observed impacts within and across systems and sectors due to their interdependence (e.g. ecosystems, health, infrastructure, the food sector). The spread of these impacts, which can move across boundaries (e.g. communities, regions, countries and continents), are often generated by the compounding effects of multiple hazards occurring at the same time, and can lead to potentially existential consequences and system collapse across a range of time horizons.

The complexity of a pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic provides a recent and evident example in which this type of complexity, and the systemic nature of risks has manifested: impacts have not just been felt in health systems, resulting from the virus itself, but also through policy responses in the form of lockdowns, which have had cascading effects. Put simply, the pandemic has had effects everywhere, starkly illustrating that our world is interconnected through systems, which come with associated, volatile risks that have revealed, and reinforced, vulnerabilities across society, with communities, countries and entire regions suffering from vastly different consequences depended on pre-existing conditions.

Similar risk characteristics and outcomes can also be observed in recent climate-related events – such as droughts – or from the global economic ripple effects of armed conflicts.

Meeting the need for a better understanding of complexity

Complexity is a defining feature of disaster risks.

This makes conventional, single-hazard and single-risk assessment approaches increasingly insufficient for comprehensive disaster risk management. This is because these types of approaches are often not well suited to account for complex characteristics and do not assess the compounding affects of multiple, interacting hazard.

This was seen, for example, when Tropical Cyclone Amphan hit the Sundarbans region of India and Bangladesh in May 2020, during a period of high COVID-19 infections, resulting in conflicting responses where people needed to gather in cyclone shelters in close confinement, but also needed to socially distance. The cyclone created additional health pressures as it destroyed hospitals and health clinics where COVID-19 patients were being treated.

Given the complexity of disaster risks, there is a growing need for new tools that can help stakeholders and decision makers understand and characterize the complexity of risks to inform comprehensive systemic risk management.

Rising to this call, researchers from United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security have developed a novel methodology: Impact Webs.

Impact Webs map the complex way in which risks and impacts have emerged and interacted across multiple sectors or systems during recent or past disaster events. The Impact Web approach draws on conceptual modelling and systems thinking, with a strong stress on co-creation with experts and stakeholders in the study area, country or region being mapped.

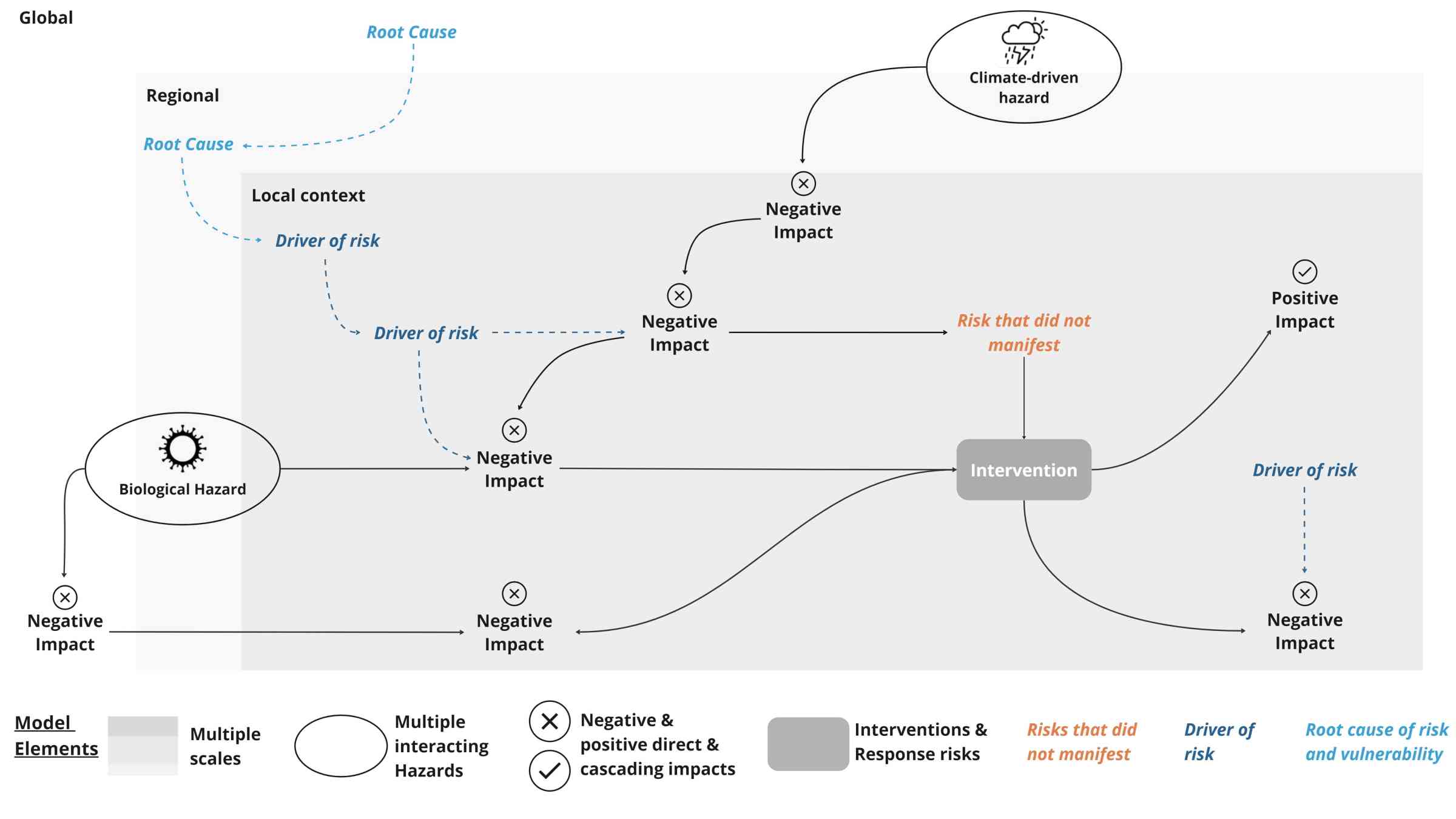

The methodology charts various risk elements to build a rich picture of systemic risks, including:

- multiple interacting hazards,

- interconnections between different risks and impacts for communities, economic sectors or systems across multiple scales (e.g. local, regional, and global context)

- drivers of risks, as well as the underlying root causes behind them,

- risks and impacts that arise from responses (e.g. policy interventions aimed to reduce risks), including positive impacts, and risks that did not manifest.

Eight steps to guide assessors

The team that developed the Impact Webs methodology has produced a guidance document providing ‘how-to’ instructions for the researchers, practitioners and consultants who are undertaking risk assessments in a given context. This context could be a regional- or country-scale systemic risk assessment for a recent hazard event, or a more targeted risk assessment at a river basin scale.

The guidance document follows eight flexible steps. Each step includes suggested data and information sources (including stakeholder engagements), expected outcomes, and guiding questions for inspiration. The document also provides a hypothetical example, in which an Impact Web is constructed step-by-step along with the user.

The eight steps are:

- Scoping – to identify key sectors, protection targets, stakeholders and sectoral/system vulnerabilities.

- Hazards, threats and shocks – including relevant past events & likely future events leading to impacts on key sectors & protection targets.

- Direct and indirect impacts (negative and positive) on key sectors and protection targets

- Interventions – put in place to respond to risks and impacts, as well as response risks arising from them.

- Drivers of risk and root causes of vulnerability for key sectors and parts of the system.

- Workshop 1, where the first order draft of the Impact Web is validated with stakeholders to ensure the system is represented correctly.

- Identification of entry points for risk management for key sectors and protection targets.

- Workshop 2, where the final order draft of the Impact Web and entry points for risk management are validated with stakeholders.

Lessons from Malawi and South Africa

Following the guidance document, the research team worked with a wide range of stakeholders to develop Impact Webs at the national scale in Malawi and South Africa.

The objective was to derive lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic and recent concurrent hazard events for understanding systemic risks. The Impact Webs then informed a discussion on opportunities for systemic risk management, in which they were used to co-create systemic risk- management and recovery pathways that strengthen resilience across multiple sectors in both countries. Recommendations focused on enabling risk-informed decision-making, facilitating inclusive and equitable recovery from disasters and exploring options for financing disaster risk management.

A practical, participatory process

Co-creating Impact Webs following the guidance document allowed the researchers and stakeholders to conclude that:

- Integrating conceptual risk models and a system-oriented approach, the methodology is a useful way to make complexity manageable for risk managers and practitioners. The process helps uncover/explore how various risk elements such as hazards, exposures, vulnerabilities, impacts, and responses are connected.

- This helps shed light on the complexity of risks in our highly interconnected world. It reveals how economic sectors and systems are set up in ways that can intensify and propagate risks and impacts.

- Co-creating Impact Webs in a participatory manner with stakeholders, gives a more representative overview of the factors that are important to them, and reduces blind spots in the risk assessment. Stakeholders could be, for example, national authorities in charge of disaster risk management, or a particular community living in a flood plain that are vulnerable to flood impacts. The co-creation process using Impact Webs can then inform preventive planning for what stakeholders most value and want to protect, thereby providing guidance for more comprehensive disaster risk management.

- Recognising the systemic nature of risks through Impact Webs supports identifying systemic solutions where positive cascading effects can be capitalised upon, ultimately contributing sustainable, long-term and systemic recovery.

In the evolving landscape of ever-more-connected communities and societies, disaster risk reduction must account for complexity. The Impact Webs approach makes a valuable contribution, offering a system-wide and participatory perspective for systemic risk management.

Edward Sparkes is a Research Associate specializing in systemic risks and climate-resilient development in the Vulnerability Assessment, Risk Management and Adaptive Planning department at United Nations University – Institute for Environment and Human Security.

Dr. Michael Hagenlocher is an Academic Officer specializing in cascading & systemic risks, global change and resilience and vulnerability & risk assessment in the Vulnerability Assessment, Risk Management and Adaptive Planning department at United Nations University – Institute for Environment and Human Security.

Saskia E. Werners is the head of the Vulnerability Assessment, Risk Management and Adaptive Planning section at United Nations University – Institute for Environment and Human Security. Her main research interest is adaptation to global change in water management. She researches how information services can be embedded in decision-making to provide actors with actionable knowledge at the right moment for adaptive land and water management.

Davide Cotti is a Senior Research Associate in the Vulnerability Assessment, Risk Management and Adaptive Planning department at United Nations University – Institute for Environment and Human Security, specializing in understanding and conceptualizing complexity in risks connected to hydrological hazards.

Editors' recommendations

- Systemic risk management and recovery pathways: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic in the Southern African Development Community

- Understanding and characterizing complex risks with Impact Webs: A guidance document

- Tackling growing drought risks - The need for a systemic perspective

- Understanding and managing cascading and systemic risks: Lessons from COVID-19