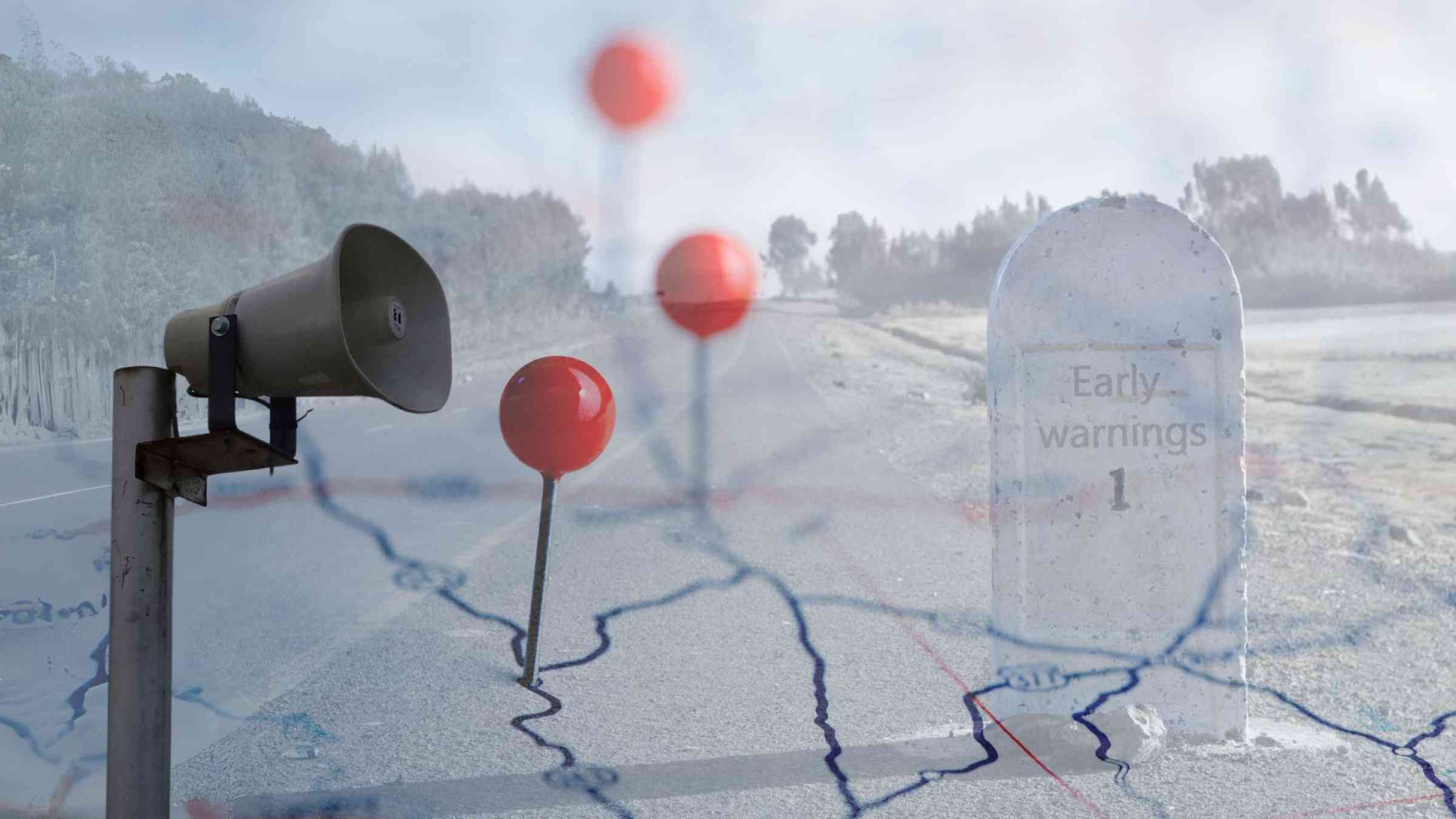

The first mile of warnings means putting people first

We must reach a major goal by 22 March 2027: Early warnings for all! On 23 March 2022, UN Secretary-General António Guterres announced this deadline for everyone to be covered by early warning systems.

The first mile of warnings begins the journey.

The first – not the last – mile of warnings

The first mile of warnings means putting people first. It means asking each other about what we need and what we offer.

Warnings are meant to be for and about people, as a long-term social process to act for, by, and with all of us.

This foundation differs from a common paradigm within warning systems – the last mile (or ‘the last metre’). The last mile aims to overcome the challenge of people needing warnings most often not being reached. Closing the gap between warnings and the people needing them (which is all of us) is seen as the final step of a complete warning system.

But the ‘last mile’ paradigm has a flaw. If reaching people – including ourselves – is the final step, how could we know that the warnings provided are what we need and would use?

If we receive a message that a lahar or storm surge is coming, but we do not know those words, are we reached? Are we instructed to evacuate to a shelter at the local school to stay safe, when we are regularly harassed and assaulted at that school? Are we told to stockpile several days’ worth of supplies in case of an emergency when we don’t even have the means to put enough food on the table every day?

Will local leaders put us first?

Starting with local leaders might not be enough.

Many of us remain excluded from day-to-day resources, decisions, and opportunities, inadvertently or deliberately. Leaders might not know about our specific needs, or they might not want to know about them, or they may know them and still perpetuate discrimination – even within their own household and family.

We cannot know how to achieve the last mile unless we change “last” into "first”—for everyone.

Consider a hypothetical fishing town in which almost all fishers are men while most women stay at home, tending to subsistence crops and livestock. The men understand the water: the waves, the currents, the clouds, any tides, and the weather over the water. The women understand the land: the vegetation, the animals’ behaviour, the clouds, and the weather over the land. Both these areas of knowledge are essential – offering different, much-needed starting points for warnings.

Women and men do not need the same knowledge. They can respect, exchange, and apply each other’s knowledge.

The last mile might involve a technical system favouring or belittling one of these areas of knowledge. The first mile fully incorporates them equitably for use.

An end to end-to-end warnings

By approaching warnings from multiple starting points, we can avoid designing warning systems as linear, end-to-end processes. We should not presume a single starting point with a single pathway to a single end point.

The warning process based on the first mile converges and branches according to our changing needs. It never really finishes, instead being incorporated into our day-to-day lives and livelihoods.

The warning threads always intersect, feeding back into each other and ensuring that we connect to learn from and teach each other. Warnings are much more than end-to-end, being end-to-end-to-end-to-end-to-end-to-end-to-end-to-end... or, perhaps, node-to-node-to-node-to-node... emphasising that the warning process never ends.

The long and the short lead times

For tornado warning times in the US, surveys indicate that people do NOT always prefer longer lead times. Longer warning times reduce the perception of tornadoes as a lethal threat and nudge some people toward trying to leave the area rather than taking shelter. Certainly, longer warning times could mean longer times in uncomfortable shelters.

Yet the assumption that we can always respond appropriately with shorter lead times might also be misplaced. How many tornado shelters – and their access routes – serve everyone’s abilities to move? And our perceptions change. Longer lead times might become more acceptable in the future, especially if the first mile works toward this preference.

Additionally, many places experience both tornadoes and flash floods. The preferred shelter location for tornadoes is below ground. The preferred shelter location for flash floods is the upper storeys of buildings. Do warnings include this information and specific action advice? Do they advise on what action to take when tornadoes and flash floods threaten simultaneously? These questions must not be considered as the storm rolls in – we must immediately begin to develop an ever-evolving warning process relevant for all of us in any weather – and for much more than weather.

Warnings are not end-to-end with longer lead times taking us to the last mile. Taking our needs and interests as the starting point reveals how we can best invest in multiple warnings, that balance lead times, availability of safer places, abilities to reach those places, and many other constantly shifting factors.

Warnings are a social process

Achieving the UN Secretary-General’s goal to reach everyone, globally, with warnings – that work for them, on their own terms – by 2027 means including the needs of all of the huge variety of people on our planet.

Warnings are about us – whoever we are – and we all need to cover the first mile.

Prof Ilan Kelman is a Professor of Disasters and Health at the UCL Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction and the UCL Global Health Institute in the UK, as well as Professor II at the University of Agder in Norway. His overall research interest is linking disasters and health, including the integration of climate change into disaster research and health research. He focuses on islands and the polar regions.

Dr Carina Fearnley is Director of the UCL Warning Research Centre and UCL Associate Professor in Science and Technology Studies. Carina is an interdisciplinary researcher, drawing on relevant expertise in the social sciences on scientific uncertainty, risk, and complexity to focus on how early warning systems can be made more effective, specifically alert level systems.