Volcano

There are more than 1,500 volcanoes potentially active in the world and more than one million volcanic vents under the sea; about 50-60 volcanoes erupt every year worldwide.

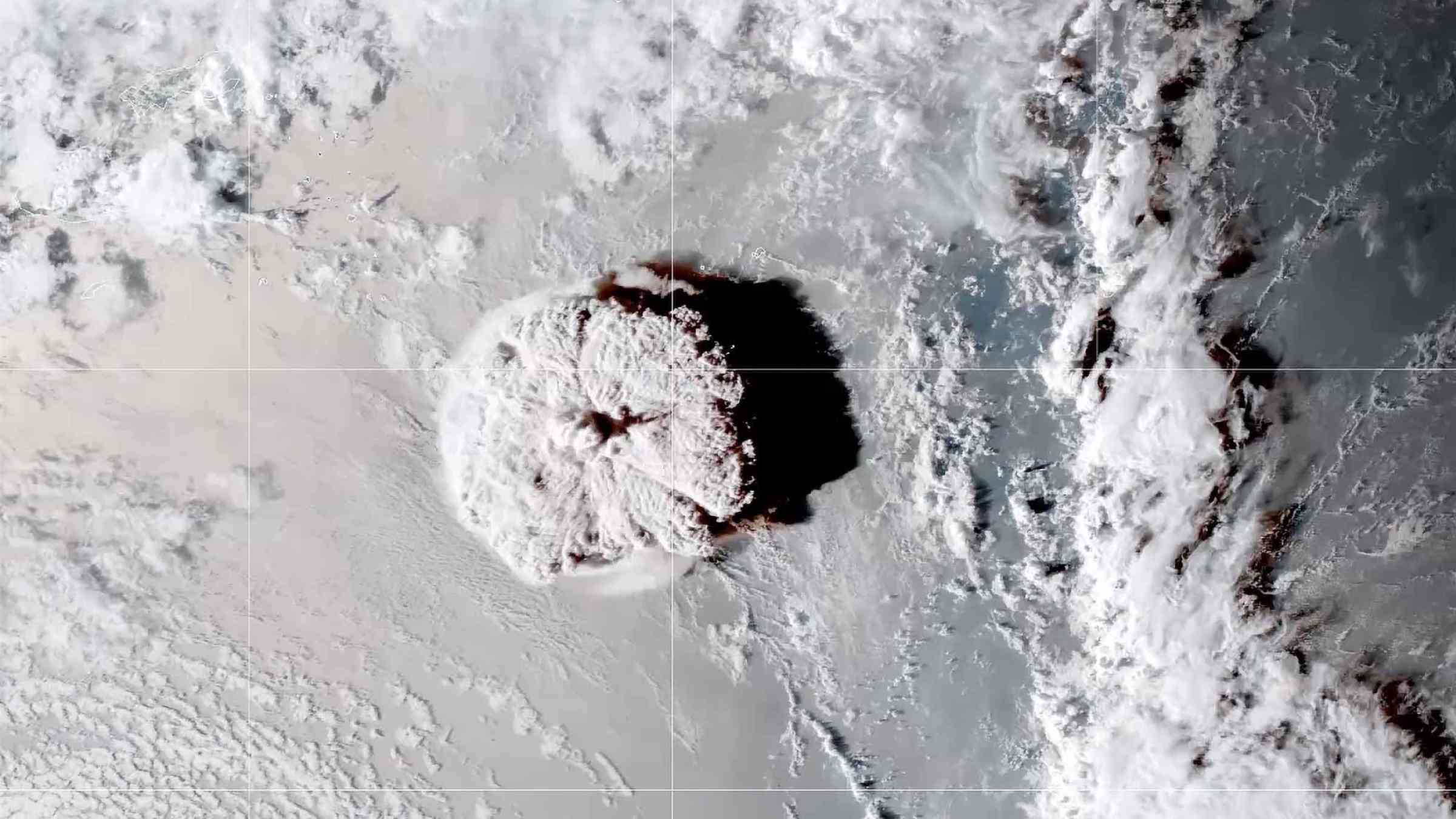

A volcano is an opening, or rupture, in the planet’s crust, which allows hot, molten rock, ash and gases to escape from deep below the surface. Volcanic eruptions can be ranked along a spectrum from quiet (effusive) to violent activity, from non-explosive, slow-moving lava flows to explosive eruptions that blast material into the air. The violence of the eruption is determined mainly by the amounts and rate of effervescence of the gases and by the viscosity of the magma itself.

Volcanoes produce a wide variety of natural hazards that can kill people and cause huge economic losses. Avalanches generated by large masses of volcanic cones sliding into the sea can trigger a tsunami. Compared to other natural hazards, such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions cause generally fewer deaths as eruptions are often predictable and people can be evacuated in time.

Other hazards associated with volcanic eruptions are lava flows. A lava flow or lava dome is a body of lava that forms during an eruption, or main eruptive episode. Lava flows are outpourings of fluid, relatively low-viscosity molten rock, whereas a lava dome is a pile of relatively viscous lava that cannot flow far from the vent (Calder et al., 2015; Kilburn, 2015).

When magma erupts at the surface as lava, it can form different types of volcano depending on:

- the viscosity, or stickiness, of the magma

- the amount of gas in the magma

- the composition of the magma

- the way in which the magma reached the surface

Types of volcano, include:

- Shield volcanoes

- Stratovolcano

- Lava dome

- Caldera

If a volcanic area is well-monitored, the movement of magma in the subsurface may be detected days, weeks or even years before an eruption (e.g., Pederson et al., 2017; Pallister et al., 2019) enabling planning, preparation and emergency actions such as evacuation. Probabilistic hazard maps can enable the appropriate land-use planning policies before eruption avoiding development in areas with high probability of inundation (Tsang and Lindsay, 2020). Attempts during ongoing eruptions to halt or divert flows (by erecting barriers, spraying lava with water, or breaking the margins of lava channels) have had mixed success (e.g., Barberi and Carapezza, 2004) nevertheless, in Hawaii, barriers have been constructed alongside new high value assets (Tsang and Lindsay, 2020). Evacuation remains the most effective strategy for protecting life and health from primary and secondary hazards (Tsand and Lindsay, 2020).

Risk factors

Although recent decades have seen remarkable progress in monitoring active volcanoes, volcano risk is increasing due to rapid urbanization and the high density of populations living on volcano slopes and valleys. About 500 million people worldwide are exposed to volcano risk and more than 60 large cities are located near active volcanoes. Volcanoes with a high hazard potential are located mainly in developing countries around the circum-Pacific belt (part of Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean and Southwest Pacific).

Vulnerable areas

Populations living close to a volcano with no monitoring and early warning systems are the most vulnerable to volcano eruption. Poor people are among the most vulnerable as they are often economically constrained to live in high-risk zones such as on the slopes of an active volcano or in nearby valleys and are less prepared to cope with disasters.

People living near volcanoes will be the most vulnerable and forced to abandon their land and homes, sometimes forever. People living far away from the eruption can be affected as their cities and towns, crops, industrial plants, transportation systems, and electrical grids will be damaged by tempura, ash, lahars and flooding.

Risk reduction measures

- Install early warning and monitoring systems to observe the behaviour of a volcano to predict eruptions and proceed to early evacuation.

- Integrate volcano risk in land-use planning.

- Ensure contingency and response plans are in place at a national and local level to evacuate people on time.

- Educate people and raise awareness on volcano risk.

- Develop probabilistic hazard maps which can enable appropriate land-use planning policies before eruption, avoiding development in areas with high risk.

- Create a hazard map to identify volcano risk and vulnerability.

If a volcanic area is well-monitored, the movement of magma in the subsurface may be detected days, weeks or even years before an eruption (Pallister et al., 2019) enabling planning, preparation and emergency actions such as evacuation.

Lahar hazard mitigation has included evacuation before eruptions or storms, channel and dam engineering, land management and early warning systems (Pierson et al., 2014). Mapping the possible paths and dynamics of lahars can help to identify exposed communities and assets.

Owing to the multiple impacts of volcanic gases, agencies in Hawaii provided a public dashboard which summarises the various impacts as well as providing access to monitoring and forecasting data (IVHHN, 2020b). The dashboard was accessed more than 50,000 times per week during the 2018 Kīlauea volcanic crisis.