Please help us improve PreventionWeb by taking this brief survey. Your input will allow us to better serve the needs of the DRR community.

Climate policy paradigms matter: Climate change adaptation in Bangladesh and Nepal

In the last two decades, Bangladesh and Nepal have been preparing various climate change adaptation policies and plans to increase the resilience of the vulnerable communities. Sumit Vij (Wageningen University & Research, Netherlands) argues that such policies and plans are based on underlying institutionalised ideas, referred to as climate policy paradigms and have resulted in one country becoming more prepared than the other.

As the climate changes, the frequency and intensity of climate-induced disasters such as flash floods, sea-level rise, heatwaves and droughts are increasing in South Asia. Although communities have been adapting to the challenges of climate change, there is an urgent need for planned adaptation to reduce the current vulnerability and increase the future resilience of the communities.

Both Bangladesh and Nepal are preparing and implementing climate change adaptation (CCA) polices. In the last two decades, the governments of the world’s two least developed countries have formulated various CCA policies, including National Adaptation Programmes of Action, National Climate Policies, Sub-national Climate Strategy documents and (intended) National Determined Contributions.

CCA policies and plan are influenced by underlying climate policy paradigms (CPPs), a comprehensive set of dominant institutionalised ideas and strategies of different policy actors, such as serving and retired bureaucrats, ministers, influential academics, donor agencies and civil society representatives. These CPPs are characterised by how policy actors choose to frame policy issues, design policy goals and allocate resources and therefore are crucial to understanding of how a country is set to tackle the effects of climate change.

Deconstructing climate policy paradigms

It’s possible to deconstruct CPPs by thinking of them as a prevalent set of ideas that are framed to reduce climate change impacts as CPPs have a specific set of policy goals, have a similar involvement of certain policy sectors to achieve these goals; and are operationalised and implemented by the government through a specific financial policy instruments. There is however insufficient knowledge about the CPPs and how a specific CPP change takes place in the cases of Bangladesh and Nepal. That is to say this kind of thinking hasn’t yet been applied to either country.

Bangladesh’s preparations for climate change

In Bangladesh, each CPP is supported with specific policy goals and financial instruments for on-the-ground implementation. For example, the Bangladesh climate change strategy and action plan demarcated clear policy instruments, institutions and sectors (agriculture, industry, irrigation etc.) to implement adaptation. This process was further strengthened when the CPP changed from adaptation to adaptation mainstreaming. In the seventh Five Year Plan (2016-20), Bangladesh linked on-the-ground challenges such as energy shortage for irrigation with climate change adaptation.

Nepal’s preparations for climate change

The CPPs in Nepal are generally weaker in design (there are no clearly defined policy goals) and implementation (there is insufficient or no funds allocated to achieve policy goals). For instance, in Nepal various policies aimed at Disaster Relief and Response and Climate Change Adaptation, but lacked substantive policy instruments and resources. According to the national capacity self-assessment report from 2008, there is a lack of capacity for climate risk management in Nepal, which explains the weak policy design.

In both countries, multiple CPPs co-exist and actors following a specific paradigm compete with one another for resources. In Bangladesh, policy actors espousing the Disaster Relief and Response paradigm (Ministry of Food and Disaster Management) and the Climate Change Adaptation paradigm (Ministry of Environment and Forests) compete for financial resources to fulfil their mandate and to implement their programmes and schemes. Similarly, in Nepal, policy actors such as local politicians and representatives of international donor agencies compete with one another.

Changing CPPs

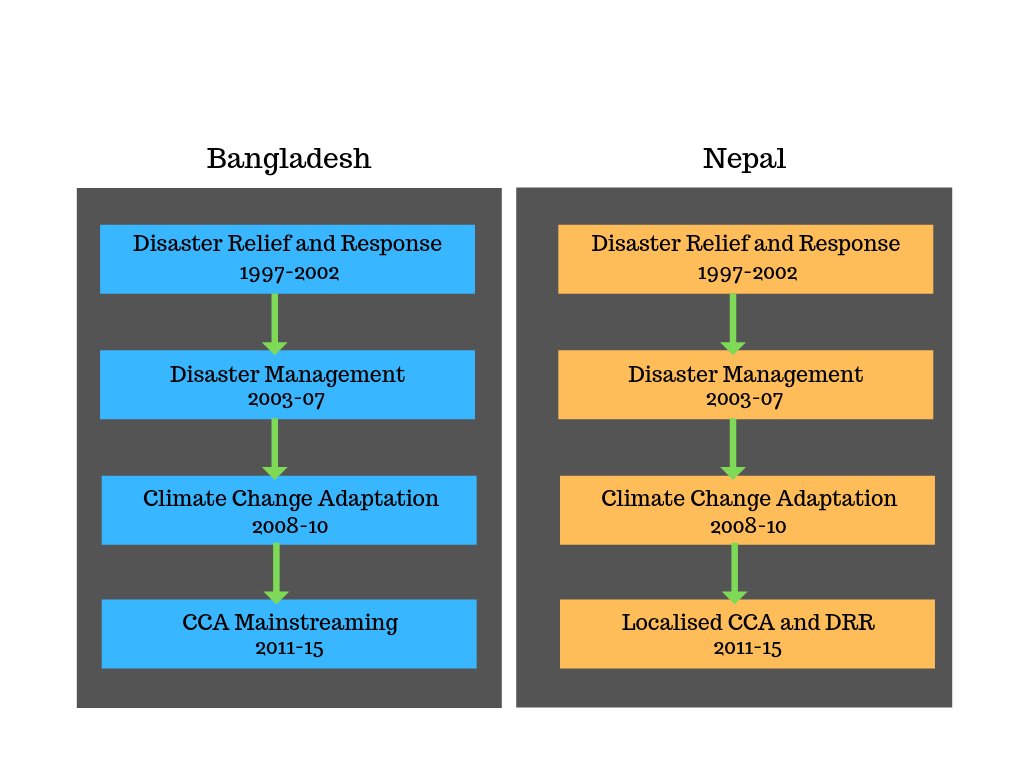

What triggers changes in climate change adaptation policies and plans? Figure 1 shows the evolution of CPPs in Bangladesh and Nepal in the last two decades. There are four key exogenous and endogenous drivers that are responsible for such change: an unstable political situation, a lack of financial support, the influence of national and international non-governmental organisations and changing global climate policy frameworks. Rahman and Giessen (2017) suggest that the CPPs in the world’s least developed countries are strongly influenced by the international arenas, particularly the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), bilateral organisations, and donor agencies. Apart from such global drivers, the interests and knowledge of national and local policy actors drive the change in CPPs. For instance, the vested interests of national NGOs to capture foreign funding and political leaders to meet the interests of voters’ influence CPPs.

Research also shows that these underlying drivers and processes of policy change are largely political in nature. Political nuances played an important role in changing CPPs. For instance, the unstable political regimes in Bangladesh and Nepal resulted in different policy outcomes. The political instability during 2006–2008 in Bangladesh brought a strong focus on climate policy, due to the involvement of academic and civil society actors. While in Nepal, due to prolonged political turmoil, climate policy institutions remained weak. The political situation in Nepal is still very unstable. Between 2011 and 2016, six different governments came in power, some lasting for only a few months. The political nature of drivers also reflects upon the nexus between the national civil society and donor agencies. The strong presence of international and national non-government organisations (NGOs) in both Bangladesh and Nepal can be attributed to the progress of climate policies. Such actors are influenced by the deliberation at the conferences of UNFCCC, IPCC, bilateral organizations, and donor agencies. Further, donor agencies support different ministries and NGOs in both Bangladesh and Nepal. These politically nuanced and fragmented efforts may create competition among various nodal ministries in the future.

Both Bangladesh and Nepal follow a similar pattern of CPPs but have recently diverged (Figure 1). Bangladesh is currently following the ‘CCA mainstreaming’ paradigm, while Nepal is following a ‘localized action for CCA and DRR’. The two countries have graduated from one paradigm to other due to the drivers of CPP change, such as an unstable political situation, lack of financial support, influence of national NGOs, and global policy frameworks. With various CPPs in place, there is always the possibility of overlapping efforts, confusion, contradiction over strategies and competition over resources between ministries involved. In the near future, both LDCs will develop and implement several climate-related documents (Bangladesh – revised BCCSAP, National Adaptation Plan, Delta Plan 2100; Nepal – National Adaptation Plan and revised LAPA framework for Nepal) based on new or existing CPPs. Policy actors in the two countries must think carefully to come up with an overarching strategy to integrate or at least recognise the existence of multiple CPPs. Designing such a strategy will support policy actors to shape, coordinate and implement future climate policies effectively.

Explore further

Please note: Content is displayed as last posted by a PreventionWeb community member or editor. The views expressed therein are not necessarily those of UNDRR, PreventionWeb, or its sponsors. See our terms of use

Is this page useful?

Yes No Report an issue on this pageThank you. If you have 2 minutes, we would benefit from additional feedback (link opens in a new window).