Sovereign risk

Sovereign risk is the economic (or financial) impact a government would face in the event of a disaster.

If the potential occurrence of a disaster is not taken into account in the government's budget and a disaster occurs, this could entail a deficit for the country, and impact negatively on the country’s creditworthiness. A sovereign risk financing strategy aims at strengthening the capacity of the government to respond after a disaster event while protecting its fiscal balance.

What is sovereign risk?

The sovereign is the State, representing its citizens. ‘Sovereign risk’, or country risk, is the risk that a government could default on its debt (sovereign debt) or other obligations. It is also, the risk generally associated with investing in a particular country, or providing funds to its government. Sovereign risk, in the context of disasters, is the economic impact a government would face in the case of a disaster which affects its citizens.

Why does sovereign risk matter?

The State has passive obligations, i.e. government expenses, some of which are direct - such as debt, budget expenses, pension passives and other social security mechanisms. Other passive obligations are indirect and classified as either explicit or implicit. Explicit are those that are also legal or contractual, but only paid if a particular event occurs, i.e. the State guarantees payment for subnational governments or private and public companies, for which, in case a certain monetary quantity is not attained, the State has to pay the agreed amount. The implicit indirect passives are not legally defined. They are also moral obligations, and it is unknown whether they will occur. This includes, for example, bankruptcy of the financial system, of social security funds, and the occurrence of disasters.

Disasters can sometimes overwhelm small island economies; the economic pressure in recovering from disasters is often disproportionate to the economic capacity of Pacific Island Countries and Territories.

ODI, 2015

If these latter expenses are not taken into account and a disaster occurs, this could mean a deficit for the country. Sovereign risk covers a potential loss that should be paid once disaster occurs (i.e. cost of recovery, reconstruction). Most developing country governments, particularly in smaller and less advanced economies, cannot afford the expense of a major disaster. If the impact were significant, the government would have to take resources from other sources to tackle these events. Redirecting funds to cover for these events would render development projects for the country secondary, and push countries further into debt.

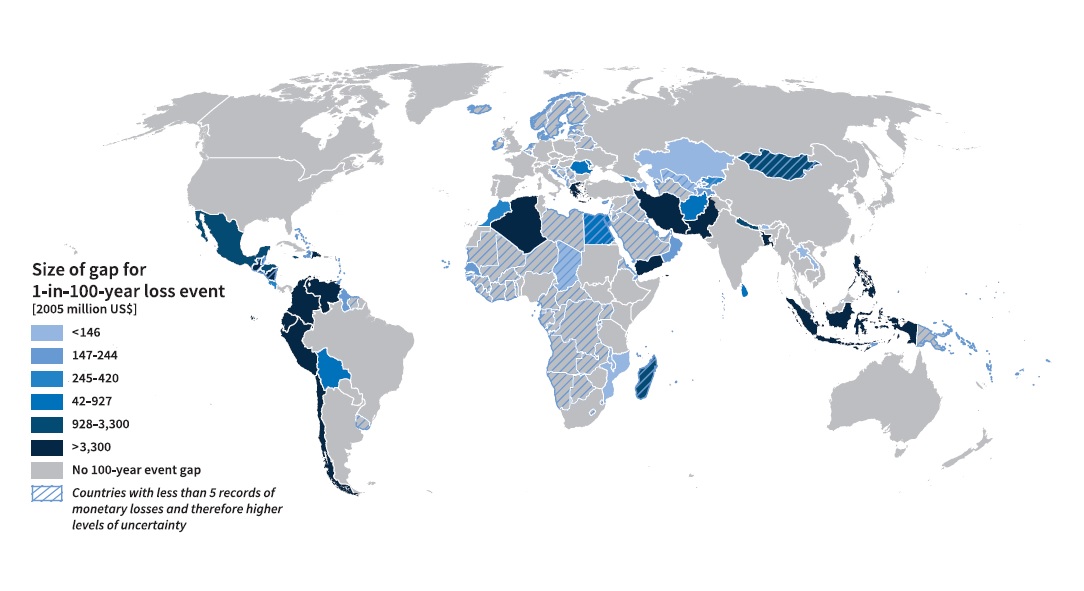

Countries facing a financing gap for a 1-in-100-year loss event (UNDRR, 2015). Countries with budget deficits or insufficient reserves may not be able to absorb this kind of loss. This is not a problem for countries such as the USA, Canada, and most of Europe (excluding Greece), however countries such as Madagascar, Pakistan, and Nicaragua would face a major financing gap.

What can be done to reduce sovereign risk?

In both disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation there is a growing enthusiasm for insurance and other forms of risk financing in order pragmatically to protect against sovereign risk and theoretically strengthen resilience. Future disasters are now accepted as contingent liabilities for the government. This means that disasters are contingent passives (potential debts) which would be real passives or actual debts for all citizens (society) when risk is materialized in disaster.

Governments are, in principle, responsible for the security of their citizens and thus the resilience of citizens should be, almost by definition, a public sector concern. However, the development of risk financing schemes normally reflects a narrower notion of the state. Often it is government and its international financial arrangements that are protected against disasters, but not the nation and the many individuals of which it consists.

Governments interested in strengthening their response capacity will generally have to combine a number of financial instruments and policies that complement each other.

As the external or internal debt must be paid, a financing strategy is necessary that includes not only how to access financial resources to cover the loss, but also how to reduce the loss in advance. This is a key incentive not only for the implementation of a decent risk assessment but risk reduction itself. Sovereign risk is a persuasive reason to make the risk management strategy a responsibility of the State, transferring accountability.

Financial protection will help governments mobilize resources in the immediate aftermath of a disaster, while buffering the long-term fiscal impact of disasters. However, a comprehensive risk management strategy should cover many other dimensions, including programs to better identify risks, reduce the impact of adverse events and strengthen emergency services.

A sovereign risk financing strategy aims at strengthening the capacity of the government to respond after a natural disaster while protecting its fiscal balance. A number of instruments are available to build such a strategy, each with its own cost structure and other characteristics.

These can be categorized as ex-post (after a disaster) and ex-ante (before a disaster) financing instruments. Ex-post instruments are sources that do not require advance planning, such as budget reallocation, domestic credit, external credit, tax increase, and donor assistance. Ex-ante risk financing instruments require pro-active advance planning and include reserves or calamity funds, budget contingencies, contingent debt facility and risk transfer mechanisms. Risk transfer instruments are instruments through which risk is ceded to a third party, such as traditional insurance and reinsurance, parametric insurance and Alternative Risk Transfer (ART) instruments such as catastrophe (CAT) bonds.

An enabling regulatory and supervisory framework is important to ensure a sufficiently robust insurance sector with sufficient financial capacity to absorb, and where appropriate transfer, disaster risks, and that ultimately prices risk correctly thereby encouraging risk reduction.

An effective financial strategy against natural disasters relies on a combination of these instruments, taking into consideration the country's fiscal risk profile, the cost of available instruments and the likely disbursement profile after a disaster.

Comprehensive disaster risk assessment identifying exposures and interdependencies, as well as the leadership of Ministries/Ministers of Finance at the national level is crucial to the development and implementation of integrated disaster risk financing strategies.

Related stories

Measuring what matters: A new approach to assessing sovereign climate risk

Understanding who and what is exposed to climate hazards is essential to pricing this risk and preparing for its impacts.

Developing disaster risk finance in Morocco: Leveraging private markets for sovereign risk transfer

Morocco now has an edge in terms of looking at how to address other crisis risks, including those caused by epidemics and climate change.

The first climate smart sovereign credit ratings

The first sovereign credit ratings to directly include climate science show many national economies can expect downgrades within a decade unless action is taken.